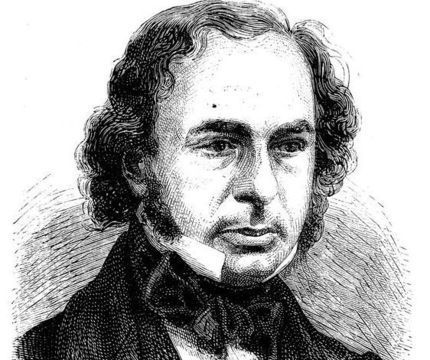

Isambard Kingdom BrunelGetty: Images

How much do you know about Isambard Kingdom Brunel?

At the start of the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution was on the march. Across the north of England, textile mills sprouted across the river valleys, turning villages into towns and towns into cities. Foundries and potteries needed coal to fire their furnaces. Factories needed to transport their goods to markets across the country and increasingly abroad. People and cargo waited to get around the rapidly changing world like never before. Britain was ripe for rebuilding and for the builders – for the likes of Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

In the rarefied field of engineering history, I.K. Brunel is one of the giants. A short, abrupt, cigar-chomping visionary, Brunel (1806-1859) was simply the most brilliant, accomplished civil and manufacturing engineer of his age. In a relatively short career, Brunel transformed English transportation – designing and building trains, railways and the tracks they run on, ships, viaducts, bridges and tunnels. Much of his work survives in use today.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel was born in Portsmouth in 1806. His French father, Marc Brunel, was a civil engineer. The young Brunel was taught first by his father and then sent to France at 14 for a classical and engineering education at the Lycee Henri-IV. Returning from Europe in 1822, Brunel cut his teeth as assistant engineer to his father on the first tunnel to be built under the River Thames. Work continued for years with interruptions before the Thames Tunnel between Wapping and Rotherhithe was finally completed in 1843. It remains in use today as part of the London Overground train network.

After several years, however, Brunel was ready to move out on his own.

Bridging the River Avon

In 1830, a company was formed for the purpose of building an iron suspension bridge across the Avon Gorge in Bristol – a span of more than 700 feet, some 250 feet above the River Avon. After two rounds of design competition, the young Brunel was declared the winner and he was appointed project engineer at age 25.

Building began on the Clifton Suspension Bridge in June 1831 under Brunel’s direction. Unfortunately, work was suspended only

four months later with the “Bristol Riots”, following the defeat of the Second Reform Bill in Parliament. Construction commenced again in 1836, but problems with financing and transporting materials caused repeated interruptions. The bridge was finally completed and opened in December 1864, 33 years after it was begun.

Now owned and maintained by a nonprofit trust, several million vehicles a year traverse the Clifton Bridge, paying a one pound toll that provides for the span’s upkeep, as it has done since the bridge’s opening. A Visitor Centre at the Leigh Woods end of the bridge provides an excellent introduction to Brunel’s engineering feat and a vantage point for seeing it up close.

Long before work on the historic bridge was completed, once again, Brunel had moved on.

The Clifton Suspension Bridge

Building God’s Wonderful Railway

In the late 1700s, a network of canals began crisscrossing the island connecting navigable rivers and seaports. Moving raw materials, manufactured goods and people by canal boat and barge was more reliable and cost-effective (not say a smoother ride) than relying on wagons and the pace of draft horses on the corrugated uncertain roads of the 18th century. Moving still at the speed of the horses that strained on the tow paths, however, canal boat transport could not keep pace with the rapidly growing demands of the emergent industrial economy.

The first steam railway in the world, the Stockton & Darlington Railway began in 1825, carrying passengers and coal on a 26-mile line from Darlington to the coast at a speed of 15 miles per hour. In a few short years, a network of rail lines exploded across the countryside and rapidly evolving locomotives carried ever-heavier train loads at increasing speeds.

In 1833, Brunel was appointed chief engineer for the newly formed Great Western Railway (GWR), charged with building a rail line from London to Bristol. He surveyed every mile of the route personally. Brunel built the viaducts, bridges and tunnels. He also designed the locomotives and both the freight and passenger rolling stock.

The London terminus of the GWR was Paddington Station, designed by Brunel and opened in 1854. Its original four tracks have expanded dramatically over the years, but Paddington’s arching iron skeleton would be recognisable to its builders today. A life-size bronze statue of Brunel sits prominently on the concourse at platform 9. Brunel-built stations along the rail route west can be seen as today at Bath Spa and Bristol Temple Meads.

Brunel’s Great Western line did not stop with its original commission to Bristol. The rails were completed to Bridgwater in 1841, a 152-mile route from Paddington that is still considered a monumental example of railroad design. The track laying continued in stages on to Exeter and finally down the spine of Cornwall, reaching Penzance in 1867.

By the early decades of the 20th century, the GWR had expanded its network from the Channel across Southern Wales and north to the Cotswolds and Oxford. It actively promoted seaside holidays on the south coast and Bristol Channel and passenger leisure travel for the first time. The GWR became known as God’s Wonderful Railway.

Spanning the Broad Atlantic

In the meantime, in 1836, the Great Western Steamship Company was formed, nominally to continue the Great Western Railway, allowing passengers as well as cargo to continue travel west from London all the way to New York. Brunel was appointed to the building

committee and volunteered his design for the firm’s first ship, SS Great Western, launched with great success in 1838.

Brunel turned his focus to naval architecture, designing and overseeing the building of three steam-powered ships for the Atlantic routes to North America. The second of these, the SS Great Britain, was the first steamship driven by screw propeller rather than paddlewheels. Launched in 1843, it was the first prop-driven, iron-hulled transatlantic ship – 100 feet longer than any ship ever built.

After several years on the Bristol-New York crossing and a grounding in Ireland, the SS Great Britain spent some 30 years carrying emigrants from England to Australia. In 1882, it was largely gutted to carry coal, and after a fire aboard in 1886, its hulk was scuttled in the Falkland Islands. Following a dramatic salvage operation in 1970, the ship’s hull was returned to Bristol for restoration. Today, the Great Britain sits mounted in drydock, refurbished to its initial glory and open to the public.

Follow the Brunel Rails to the West

You can find I.K. Brunel’s crowning achievements on route to the West Country. Travel by car if you must, but this is a journey for the Great Western Railway. Take the train from London Paddington to Didcot Parkway. The Didcot Railway Centre is a rather gritty visit. Home of the Great Western Society, the Center is located in the huge railyards of Didcot Parkway Station on the GWR mainline west.

Describing itself as the “Living Museum of the Great Western Railway,” Didcot is a working railyard, with sheds full of vintage steam locomotives spanning almost 100 years. At active locomotive workshops, volunteers rebuild, repair, restore and keep running these dramatic icons of industrial and social history. As importantly, they pass on to younger enthusiasts their knowledge and skills.

About 20 miles west of Didcot, the small Wiltshire market town of Swindon grew quickly after Brunel chose it as the new GWR Locomotive Repair Facility in 1841. Soon, the Swindon Works was building engines as well as carriages and wagons. By the early 20th century, Swindon became one the world’s largest railroad works, covering more than 300 acres and employing 14,000 men and women. The Locomotive Department built 100 engines a year and repaired more than 1,000. Its Carriage Works built 250 coaches and repaired some 12,000 carriages and wagons a year as Brunel’s rail network expanded through the West Country and Wales.

Swindon Works went quickly into decline following rail nationalisation in 1948 and the end of steam locomotive production in 1960. The Works was closed in 1986 after 145 years. Today it is a showcase of Brunel’s work: STEAM: The Museum of the Great Western Railway. Every aspect of the works at Swindon is recreated and explained in order, from the stores of raw materials and the foundry to the finished steam locomotive.

Continue on from Swindon a short train journey of 40 minutes to Bristol to visit the Clifton Suspension Bridge and SS Great Britain.

As an architect, mechanical and civil engineer, Brunel’s record of accomplishment in a 30-year career is unexcelled. It wore him out. Isambard Kingdom Brunel died in London in September 1859, aged just 53. His legacy is easily seen today but difficult to quantify. In 2002, a broad BBC public poll to determine the 100 most influential Brits in history found Brunel at number 2. His were indeed the shoulders of a giant.

Thames Tunnel

In the original engine house at the Rotherhithe end of the Thames Tunnel, the Brunel Museum unpacks the construction of the tunnel, offers guided walking tours and shares the story of Britain’s most famous engineer. Open daily 12-4 pm weekdays, 10am - 5 pm weekends.

www.brunel-museum.org.uk

Didcot Railway Centre

On Brunel’s original line from London to Bristol, the entrance to the living museum of the GWR is right in the ticket hall of the Didcot Parkway Station, a 40-minute journey from Paddington. Open weekends through the off-season and daily from April through September.

www.didcotrailwaycentre.org

Clifton Suspension Bridge

The Clifton Suspension Bridge Visitor Centre, on the B3129 at Leigh Woods is most easily accessible from Clifton Village. From central Bristol, best take a taxi, local bus or follow the Avon Trail riverside walk. Open daily throughout the year, 10am – 5pm.

www.cliftonbridge.org.uk

SS Great Britain

Take a taxi, bus or ferry from Bristol Temple Meads station to the Great Western Dockyard where the SS Great Britain was built. After touring the famed steamship, visit the new museum, Being Brunel, is in the historic dockyard. Open daily 10am - 6pm.

www.ssgreatbritain.org

* Originally published in the July / August 2020 issue of British Heritage Travel magazine.

https://subscribe.britishheritage.com/I**HICB

Comments