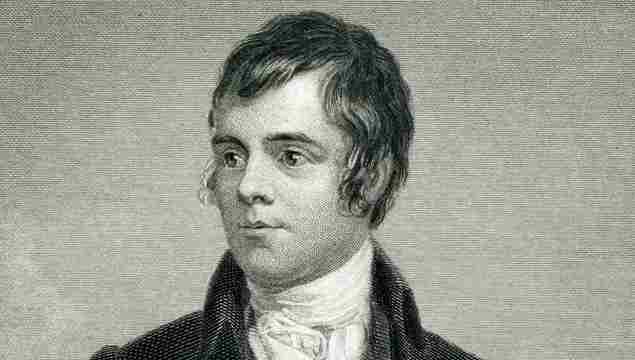

Engraving From 1873 Featuring The Scottish Poet, Robert Burns. Burns Lived From 1759 Until 1796.Getty

Scotland's most famous poet is Robert Burns. Here's everything you need to know about "Rabbie Burns".

There are apparently more statues of the Scottish poet Robert Burns in the US than anywhere else outside Scotland. So why is an 18th-century Scot, who wrote largely in the Scots language, of international importance?

Part of the attraction is his reputation as “the plowman poet,” yet there is much more to Burns than that.

The family, then known as Burnes or Burness, originally lived in the northeast of Scotland. In search of a better life, William Burnes moved around the country before finally settling in Ayrshire, where he met his wife Agnes. Their first child, Robert, was born in a but-and-ben (a Scottish term for a simple two-roomed thatched cottage) at Alloway, built by William himself, on January 25, 1759. Within days of Robert’s birth, the gable end of the building collapsed in a storm, and Agnes and baby had to seek refuge in a neighbor’s house. It was an inauspicious start, but certainly not an ill-omen of what was to follow.

Read more

Robert Burns & Education

The idea many people have of Burns is that he was a self-educated man, but that is far from the truth. Despite the hardship of his simple farming life, William knew that education was important for his sons, and he employed an 18-year-old, John Murdoch, to teach the boys. Today that may appear to be a token gesture, but Murdoch was extremely capable.

According to Burns’ younger brother, Gilbert: “With him, we learned to read English tolerably well, and to write a little. He taught us, too, the English grammar; but Robert made some proficiency in it, a circumstance of considerable weight in the unfolding of his genius and character.”

Robert built on this foundation as an avid reader, eagerly devouring any books that were available to him. Murdoch went on to teach in a school in Ayr and Robert was able to continue his education there on occasions, although his attendance was often restricted by his farming duties. The result was that Burns was fluent in English and in his native Ayrshire dialect, both of which he would use to great effect in later life.

Burns was undoubtedly conditioned by important events around him. Born little more than a decade after the Jacobite uprising in Scotland, he lived during both the American War of Independence and the French Revolution and supported their ideals.

Despite never traveling further than around Scotland and the north of England, he was an internationalist in his outlook.

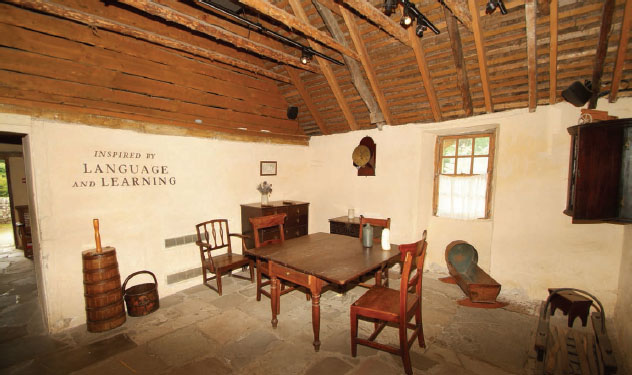

Here in the two-room thatched birthplace cottage in Alloway the Burns family worked, ate and slept, and shared the house with the animal byre

Here in the two-room thatched birthplace cottage in Alloway the Burns family worked, ate and slept, and shared the house with the animal byre

As a result, Burns the radical was very much a “common man,” a fact which for all his fame he never forgot. Like most writers, he was a keen observer of the natural world and the society around him. He was also an idealist, a romantic and a satirist, while at the same time someone endowed with great imagination.

Robert Burns & Tam o Shanter

These elements come together in his famous poem, Tam o Shanter, a tale of a farmer, who, having over-indulged in alcohol, rode home at the dead of night. Spotting lights in the old church at Alloway he stopped for a closer look, only to see witches and warlocks dancing. Tam, forgetting himself, called out, and within seconds he was riding for his life, pursued by the unholy host. Tam was well aware that witches could not cross running water, so he knew if he could cross the bridge over the River Doon he would be safe. Tam escaped, but only just, the leading witch managing to grab his mare Maggie’s tail, leaving the poor beast with only a stump. It is an epic poem, written in a rhythmic way to portray the chase, while not meant to be taken too seriously, and it is one he probably never bettered.

The romantic Burns also wrote many fine songs and Bob Dylan claimed to have been inspired by the poet’s finest love song, “My love is like a red, red rose.” Lines such as “Till a’ the seas gang dry, my dear, And the rocks melt wi the sun, And I will love thee still my dear, while the sands o’ life shall run” would surely charm any woman.

Robert Burns & Scandal

Yet Burns undoubted talent could have been lost to the world. In 1786, the poet’s life was in something of a turmoil. He had fathered an illegitimate child - the first of at least four - and gone through a form of irregular marriage (acceptable under Scots Law) to Jean Armour, who was pregnant with what proved to be twins. Jean’s father was furious about her taking up with a man he saw as a waster, and he issued legal action against Burns, seeking to have him arrested and forced to pay a large sum in damages.

In Burns’ view, there was only one way out and that was to immigrate. He was on the point of leaving for the slave plantations in Jamaica to take up a post as a bookkeeper there. However his book, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, generally referred to as the Kilmarnock edition, became an instant success, selling out within weeks, and so relieving some of the financial pressures and ensuring his celebrity status. This caused Burns, and Jean’s father too, to have second thoughts; Jean became his wife and bore him a total of nine children.

A second edition was published, and versions of the poet’s work were soon being printed in the larger cities of the English-speaking world, including London, Dublin, Philadelphia and New York. His success made him a favorite with the cream of Edinburgh society, although they are quickly tired of him; class distinction meant he would always be the plowman, albeit a very talented one.

Robert Burns & Agriculture

In 1789, the same year as the start of the French Revolution, Burns became an exciseman to supplement his meager income from farming, although he continued to work Ellisland until 1791. By then it was clear that the farm had no future, and Burns gave up the lease on Ellisland and moved to Dumfries. The following year he was promoted and in 1793 he and his family moved to Mill Vennel, now called Burns Street.

The house was well appointed for the time and Jean and the family continued to live there after Burns’ death thanks to income from his poetry, his government pension and the generosity of his supporters. A biography, written by Dr. James Currie, also raised a considerable sum for the family.

Unfortunately, Currie, a reformed alcoholic, was largely responsible for portraying Burns as a heavy-drinking womanizer. In fact, the poet had a weak stomach and simply enjoyed the social element rather than drinking. Certainly, he was fond of the opposite sex, and they of him. With such a silver-tongued way with words, the girls must have been drawn to the 18th-century celebrity.

Burns died in Dumfries on July 21, 1796, aged just 37, his body broken by agricultural labor and the poor climate. The likeliest cause of death is now believed to be endocarditis - inflammation of the heart lining - probably caused by an earlier bout of rheumatic fever.

Because he had been a member of the local militia, the Dumfries Volunteers, Burns was given a military funeral. A large crowd lined the streets and the volunteers fired a salute over his grave. He was buried in a quiet corner of the churchyard, but in 1813 an appeal was launched to build a fitting memorial for Scotland’s greatest poet, with subscribers including the Prince Regent, later King George IV. A fine mausoleum was built and on September 19, 1817, Burns's body was exhumed and reburied there.

The story of Robert Burns is a fascinating one, but if you can’t make it to Scotland do at least access his work online. You may initially encounter difficulties with the Scots language, but it is worth persevering. “The plowman poet” is truly worthy of a greater audience.

* Originally published in 2017.

Comments