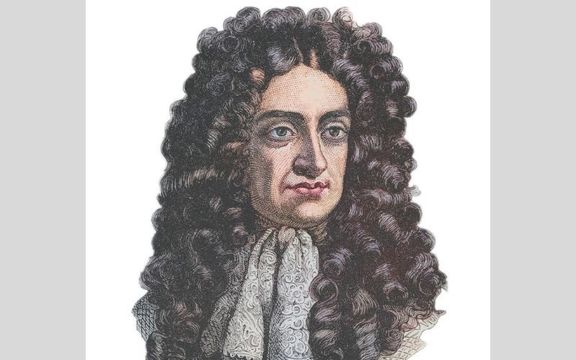

Portrait of King Charles II of England Getty

Known as ‘The Merry Monarch’, King Charles II famously united dissenting factions under his reign, from 1660 to 1685, which came to be known as the Restoration Period.

After a triumphant return from exile in Europe, Charles II took back the title and throne that had been his father’s, restoring the monarchy, and treading a delicate balance to maintain it, as religious tensions endured. He became known as the Merry Monarch—his hedonistic ways in stark contrast to the puritan regime he replaced.

Charles was born on 29 May 1630, in St. James's Palace, London, the second and eldest surviving son of Charles I and Henrietta Maria of France, who was a Roman Catholic. He was baptised at the Chapel Royal, by the Anglican Bishop of London, William Laud and was conferred the titles of Duke of Cornwall and Duke of Rothesay. He later took up the title of Prince of Wales. The young prince was placed under the governorship of William Cavendish, Earl of Newcastle and tutored by Dr Brian Duppa, the Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, and a protégé of Archbishop Laud.

In light of his mother’s religion, the Long Parliament kept a close watch on Charles’s education and religious development. In 1641 the Earl of Newcastle was alleged to be involved in the Army Plot and William Seymour, Marquis of Hertford, replaced him as Charles’s teacher.

Early exile

In the spring of 1642, relations between King Charles I and Parliament were deteriorating, and he sent his wife to The Hague for safety. Despite the protests of Parliament, the king left London for the north and took his heir with him.

The young prince was appointed nominal commander-in-chief of Western England, and at just 12 years of age, fought alongside his father at the Battle of Edgehill, the first battle of the English Civil Wars.

As the wars raged on, young Charles spent many years in exile on the continent. He fled first to the Isles of Scilly, followed by Jersey and finally to France. By 1648, he relocated to The Hague, where his sister Mary and brother-in-law William II, Prince of Orange aided him in the royalist cause.

Charles I was beheaded at Whitehall on 30 January 1649. That year the Parliament of Scotland declared Charles II to be the King of Great Britain and Ireland, and invited him to come to Scotland. However, the English Parliament made the declaration unlawful and England entered the period known as the English Interregnum or the English Commonwealth, during which the country was a de facto republic, led by Oliver Cromwell.

However, the invitation to Scotland came with a proviso—Charles II had to accept Presbyterian Church governance, above which made him unpopular in Episcopal-governed England.

On 1 January 1651, the Scots crowned Charles II at Scone Palace, the last such coronation ever to take place there. By July, the English army marched into Fife and then captured Perth, while the Scottish forces moved south meeting defeat at the Battle of Worcester on September 3, 1651, which ended the civil war. Oliver Cromwell became the Lord Protector of Scotland, England, British Isles and Ireland, and evading capture, Charles II once again went into exile, spending another tranche of his life begging fortune and favour around Europe, in France, the Dutch Republic and the Spanish Netherlands.

Restoration

In 1658, Oliver Cromwell passed away and his son Richard became the next Lord Protector. Richard, however, did not have any power with the Parliament and abdicated the following year. The ensuing political crisis led to the restoration of the monarchy, and Charles II was invited to return to Britain.

He landed at Dover on May 25, 1660, and on May 29, his 30th birthday, he was received in London to public acclaim, and great festivities. The Restoration Settlement resulted in the return of the monarchy, the House of Lords and the Anglican church. Separate parliaments for Ireland and Scotland were also reinstated.

Due to the lengthy preparations and the fact that a new set of regalia, including a crown, had to be made for the occasion—as the previous set had been melted down during the Commonwealth period—it was almost a full year before the coronation took place.

On April 22 1661, Charles II made the traditional coronation procession from Tower of London to Westminster Abbey, and was crowned there the following day, April 23, St George’s Day. This coronation was the last time the procession from the Tower of London took place. The coronation cost over £12,000, and was recorded by Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist, who was at the ceremony and detailed the service in his writings. It was the first time that tiered seating was constructed in the transepts so that the congregation could see the ceremony. Previously a specially built raised platform had been built for the ceremony, which the monarch would ascend to via steps. After 1660, all legal documents were dated as if Charles II had succeeded his father as king in 1649.

The Restoration is a distinctive period in British history, a stark contrast to the sobriety of the preceding years. It saw the re-opening of theatres, resulting in a bawdy new theatrical genre known as Restoration Comedy, which was mainly concerned with marriage and love affairs. It echoed the looser morals of the age, and King Charles II and his brother James scandalised society with their romantic affairs. Charles publicly paraded his married mistress, Barbara Villiers, by whom he fathered a child, while James shocked by marrying a commoner. However Charles realised he must have a queen, and married Catherine de Braganza, daughter of King John IV of Portugal. Her generous dowry included two million crowns and the cities of Bombay and Tangiers. They married in 1662. The couple shared no common language, and had no children. However Charles soon fathered a second child with Barbara.

Challenging times

It wasn’t all fun and games, however, and Charles II faced several great crises and challenges during his reign. From 1665 to 1666, the Great Plague of London gripped the city, and it is estimated the death toll climbed to around 100,000 over the course of it. The upper classes left the city in droves; Charles II and his courtiers went first to Hampton Court and then Oxford.

Lockdown is not a new concept—Charles II issued a formal order in 1666 forbidding all public gatherings, including funerals. Theatres had been shut down, and pub licensing curtailed. The universities of Oxford and Cambridge were closed (Isaac Newton was among the students sent home). Shopkeepers and priests asked their customers and congregations to drop their coins in vinegar—the hand sanitiser of its day.

No sooner had the spread of the plague begun to decline, than London was hit with another disaster. The Great Fire of London, started on Sunday, September 2, 1666, in a baker’s shop on Pudding Lane, and burned until Thursday, September 6. It engulfed around 13,000 houses, and 87 churches, and St Paul’s Cathedral, destroying the medieval city centre. Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary that even the king was seen helping to put out the fire.

The major foreign policy issue of Charles’ early reign was the Second Anglo-Dutch War, which was hammering the economy when the plague hit. After the English navy’s losses at the hands of the Dutch Fleet, Charles II feared that England was vulnerable to invasion from France in its weakened condition, and sent his sister Henrietta to strike a deal with Louis XIV of France.

As the city of London rose up from the ashes of the fire, science and commerce offered hope for the future. Charles signed a treaty with the Dutch and soon after a formal alliance with Holland and Sweden was created. Furthermore, he supported the formation of the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge (today known simply as the Royal Society), which was at that time led by Robert Hooke, Robert Boyle and Sir Isaac Newton.

During this time the king pensioned off his first mistress, Barbara, and was linked to a string of women, including, famously, the orange seller turned actress Nell Gwyn. His new favourite mistress, the French-born Louise de Kérouaille, Duchess of Portsmouth, is said to have been the source of information that a French astronomer, Sieur de St. Pierre, had devised a means of determining longitude at sea. With trade and battling all taking place at sea, improving maritime navigation was a matter of great importance at the time. Not wishing to be left behind in this most important subject for merchant and naval ships, Charles II founded Britain’s first state-funded scientific research institution, the Royal Observatory.

Succession tensions

The final phase of Charles II's reign was taken up mainly with attempts to settle religious dissension, and avert rebellion. In 1670, signing the Treaty of Dover, he had given his word to his first cousin, Louis XIV of France, that he would prevent persecution of Catholics and indeed that he would at some point convert to Catholicism. Louis agreed to aid him in the Third Anglo-Dutch War and pay him a pension. However, the majority of the members of the House of Commons were loyal Protestants and when he passed The Royal Declaration of Indulgence, in 1672, in an attempt to grant religious freedom to Protestant nonconformists and Roman Catholics, the Parliament forced him to withdraw it.

Following years of tensions, in 1681, Parliament was poised to declare itself in charge of the royal succession. Charles dissolved it before they could pass a bill which would exclude his Catholic brother James from succeeding to the throne—as none of his own children were legitimate, they were excluded from the line of succession.

In 1685, at the age of 54, Charles died from a stroke. He died in his bed, surrounded by his beloved spaniels, friends, and family, in the early hours of February 6. Before he died, although incredibly weak and in great pain, he asked to see each of his surviving children and mistresses. He also requested the curtains to be drawn back, so that he could see the sun over the Thames for one last time. His final days were torture, due to scant medical knowledge of the day. His doctors bled him repeatedly over the course of five days, and applied heated cups to blister his skin and scalp. Among the peculiar potions they force-fed him were drinks made of crushed pearls, opium, wine, ammonia, extract of human skull (taken from a man who met a very violent demise), as well as a gallstone (bezoar stone) from an East Indian goat. They also gave him enemas and applied pigeon droppings to his feet. Death, when it came, on the sixth day, must have been a release for him.

His coffin lay in state in the Painted Chamber within the Palace of Westminster before burial in Westminster Abbey on 14th February in a vault in the south aisle of Henry VII's chapel. Instead of a funeral effigy, as had been usual at previous royal funerals, only an imperial crown on a purple cushion lay on the coffin. The occasion was not as elaborate as most royal funerals, probably as a result of his religious conversion. No monument was erected for him, although a life-size wax effigy stood by his grave for over a century. However, statues can be seen today in Soho Square, Edinburgh's Parliament Square, Three Cocks Lane in Gloucester and Lichfield Cathedral.

Comments