Have you ever been to Ludlow?

The late, great poet laureate John Betjeman called Ludlow “probably the loveliest town in England.” He might well have been right. Alas for poor Betjeman, he knew the town well before its rise to fame in recent years as a heartland of culinary skill and incomparable cuisine. In fact, barring only London itself, the small southern Shropshire market town lays claim to being the virtual culinary capital of England.

Or so I’d heard. It only seemed fair that I sally forth to Shropshire and report on the matter for British Heritage readers. And Ludlow does have to be sallied forth to. It’s not on the road to anywhere. Lying between Leominster and Shrewsbury near the Welsh border, the town is a good two hours’ drive west of the city center of Birmingham. It seems an unlikely spot to be reckoned a culinary heaven.

Read more

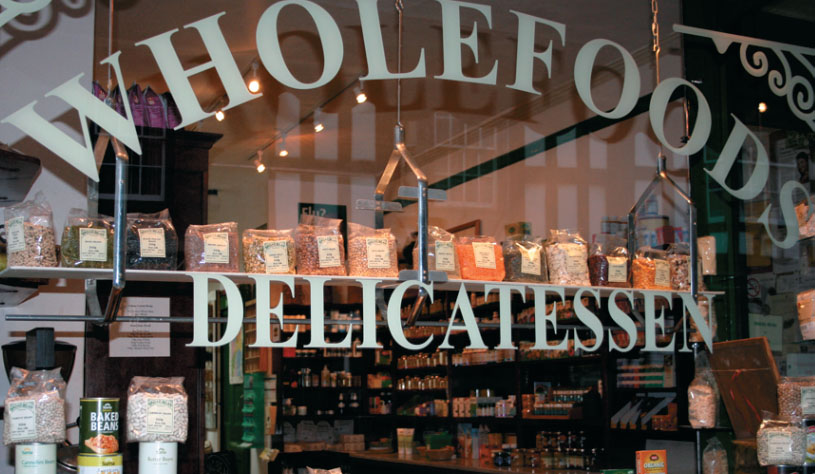

The basics are easy. There are seven restaurants in and about Ludlow listed in the Michelin guide, two of them with stars. Five local butchers make their own sausages and pork pies, and fiercely contest for the annual awards given by both local foodies and a panel of experts. Four local bakeries turn out daily rations of breads, cakes, pastries and savories. Specialist shops and delis deal everything from cheese to chocolate. The regular twice-weekly local market is supplemented by a popular bimonthly farmers market.

In fact, if you are beginning to pick up the theme, you are right: Local to Ludlow. Fully 15 shops in Ludlow as well as its open air farmers markets belong to the initiative, stocking comestibles of all sorts produced within 30 miles of Ludlow.

I started my own culinary adventures in Ludlow at The Globe, a lounge bar featuring Thai tapas. I nibbled on prawn toast with sesame seeds and sweet chili sauce, and gleow grob, delicate fried wantons filled with marinated minced chicken and prawns.

At the Unicorn Inn, I visited with landlord Graham Moore over a pint of Salopian Brewery’s Darwin’s Origin, the expert’s choice on the Real Ale Trail at the recent Ludlow Food Festival, brewed up the road in Shrewsbury. The local Ludlow’s Best was excellent as well. That was brewed just across the road. Graham also foisted upon me a sample of Cleric’s Cure—what his grandmom called “a sniff of the barmaid’s apron.”

I ordered the chef’s homemade Shropshire paté with sweet onion marmalade. It was smooth and light, almost a mousse rather than a paté. Among other interesting menu options was a hunter’s cottage pie with minced venison, rabbit and pigeon. A special that evening was grilled rainbow trout with tarragon and black olive butter. Not your customary pub fare. But then, almost every pub in Ludlow is a gastropub. In fact, virtually every eating establishment in town makes an advertised virtue out of its food: local to Ludlow. Undoubtedly no other could stay in business.

At the Ego café bar, I finished up the evening with the Ego sausage sandwich: a local pork, sage and cider sausage on brown bread baked across the street, with old-fashioned piccalilli and homemade coleslaw. One of the specials at the Ego that night was Shropshire fidget pie, made with bacon and apples from? You guessed it: right nearby.

We did seem off to a promising start. I waddled back to my room at The Feathers, a famous half-timbered hostelry that’s been receiving guests since 1647. The breakfast menu next morning made a point of announcing that the sausage was by D.W. Wall’s, again, just up the street.

The town grew up around Ludlow Castle, begun in 1090, one of a string of Norman castles built along the Welsh border. Lords of the castle, the de Lacys and the Mortimers, brought Ludlow onto the national stage. From 1472 to 1689 Ludlow Castle was the headquarters of the Council of the Marches, charged with governing the border counties. Ludlow became a powerful center of government administration, with both civil and criminal courts located at the castle. The ill-fated sons of Edward IV learned here of their father’s death. Prince Arthur and Catherine of Aragon honeymooned here before Arthur’s youthful demise of tuberculosis. Mary Tudor and her court wintered here from 1525 to 1528.

DANA HUNTLEY

The town itself was laid out on a grid in the 12th century, and clearly defined by its 13th-century walls. One gatehouse and the original grid pattern still survive. Today, Ludlow may be a little quieter than in its medieval past, but with a population of something over 10,000, including the suburbs, it still serves as the market town for surrounding villages.

The Ludlow Food Centre on the outskirts of town has been open just a couple of years. It features all manner of local foods from fruits to fruit brandies, charcuterie to chutney, cheeses to choux pastries—made there on the premises in kitchens surrounding the market hall.

I visited with marketing manager Tom Hunt, who confirmed that indeed many of the foods at the center are grown or reared there on the Earl of Plymouth’s 8,000-acre estate and that the finished foods are produced in-house. “A full 80 percent of the products we sell come from the four counties of Herefordshire, Worcestershire, Shropshire and Powys,” Hunt says.

“We have a dairy on the estate making cheeses, butter and ice cream, and we grow all our own lamb, beef and pork. The bakeries here make fresh bread seven days a week using local flour.

“Our production kitchens cure the hams and make ready-made meals with all the ingredients coming from just a few miles down the road. We make all our own pasta and pastries. We also roast and grind our own coffee.”

Inevitably, Hunt predicts, our supermarket culture will have to change. “We don’t have to have strawberries flown in from Spain in the middle of the winter. Here, everything is fresh, seasonal and local. Here, everything you see, touch and taste is real, and the money you spend supports local growers, manufacturers and suppliers.”

DANA HUNTLEY

DANA HUNTLEY

Hunt’s summary was succinct: “Ludlow is the foodie capital of half of England. We complement and contribute to that.”

This year, the Ludlow Food Centre won the national marmalade competition and the national jam competition. Croft Gold, a cheddered cheese rind-washed in Herefordshire cider brandy is one of their three cheeses that won prizes from the British Cheese Awards. They also won the pork pie competition at the Ludlow Food Festival—in itself no small achievement.

Having thus worked up an appetite, I took a light lunch at the Charlton Arms Hotel—a baguette of local ham with a pint of pear cider made, yup, just down the road. Like virtually everywhere else in town, the Charlton Arm boasts a menu replete with local cheeses, meats and chutneys.

As if its regular culinary delights were not sufficient, spring and autumn folks from all around flock to town for those acclaimed Ludlow Food Festivals. Not surprisingly, the annual three-day September show is the bigger event, when the countryside is pouring out its bountiful harvest. Covering the huge acreage of Ludlow Castle and spilling out of its curtain walls, marquees and stages, pavilions and markets host tastings, demonstrations and events. Ticketed trails allow attendees to move through town sampling ale, bread and sausages and to vote for their favorites. The competition is obviously fierce.

That evening, I started gingerly on the tapas menu at The Parkway, sampling giant butter beans with fresh basil, piquant bandelaros and pork meatballs in garlic and coconut curry. A more adventurous palate might have tried Herefordshire snails in garlic butter, Catalan-style, almond-crusted frogs legs or smoked sweet paprika-baked baby squid. Chef and owner Dean Banner also sent out a demitasse of potato and three-cheese soup that was creamy and lovely. Banner’s been part of the food scene in town for years. We chatted a bit, and he was obviously proud to be one the local culinary institutions.

Later, at the Church Inn, I tucked into this year’s winning pork pie, with pickled onions, gherkins, chutney and a beetroot salad. That went down with Frank Robinson’s flagon cider, cloudy, dry and appley, made three miles away.

In a futile attempt to help work off my culinary indulgences, the next morning I climbed the 200 narrow circular stone stairs of St. Laurence’s Church tower. Like most structures in the old downtown, Ludlow’s parish church has been around for a while. One of only a fistful of five-star churches listed in Simon Jenkin’s well-known England’s Thousand Best Churches, St. Laurence’s is well worthy of its standing as “the cathedral of the Marches.” The views from the top of its domineering tower spread in every direction across the farmland, forest and orchards whose bounty I had been savoring.

DANA HUNTLEY

I skipped lunch in order to take proper afternoon tea at De Greys, an institution on the Borders that has been virtually unchanged in more than 80 years. Yes, fluffy scones, cakes and bread were all baked there on the premises, and all are available at the bakery shop that fronts the popular luncheon and tea room with its half-timbered frontage on Broad Street dating from 1570.

As a change of pace that evening, I went to Golden Moments, reckoned the finest of Ludlow’s three Indian restaurants. I started with the customary poppadom and pickle, and then went on to a clay-oven masala, blending sheikh kabob, tandoori chicken and lamb in a buttery-smooth masala sauce mopped up with a glistening naan bread straight from the tandoor. I did wish I could sample more, but what I had was as fine as any Indian cuisine I’ve enjoyed outside of London.

The next day, regular British Heritage writer Siân Ellis drove up from Monmouthshire to share what would be the grand finale—lunch at La Becasse. That one required reservations a couple of weeks in advance, and they just squeezed us in.

Siân began with beetroot-cured salmon with horseradish ice cream and beetroot spaghetti. I choose Jerusalem artichoke mousse, parmesan gnocchi and artichoke salad with autumn truffle dressing. But they only arrived after the chef had teased us with a celeriac velouté and sundry amuse bouche.

DANA HUNTLEY

Getting to Ludlow

By Train: You can travel by train to Ludlow throughout the day in under four hours from London. From Paddington Station, change in Newport. From Marylebone, change in Shrewsbury.

By Car: Take the M40 to Oxford, then the A44 through the northern Cotswolds and the Vale of Evesham. At Leominster, turn north on the A49 to Ludlow. Journey time depends on the number of stops you make along the way, but allow five hours from London.

Then, Siân had a Mortimer Forest venison pie, with chestnuts, honey-roasted parsnips and cassis jus. I had wanted to try the local rare-breed pork belly and white bean cassoulet, but ended with pan-fried plaice fillet with a shellfish and parsley sabayon. Life’s tough.

After a bit of cheese and the chef’s pre-dessert, I finished with a dark chocolate and smoked tea fondant with banana, lime and balsamic salsa and salted caramel sauce. By that time, my eyes were so glazed that I’m not certain, but I think Siân had something with poached plums, blackberries and candied hazelnuts.

Will Holland, the UK’s youngest Michelin-starred chef, graciously came down from the kitchen to chat for a bit. “It is exciting to be a part of Ludlow’s food scene, where everything is local and fresh and appreciated,” Holland acknowledged. Modest and self-effacing, the young Bristol-born Holland was a genuine pleasure to meet. After just a couple of years here, Holland is something of a local celebrity, not only with his Michelin star, but also with a rare three rosettes from the AA.

“I never wanted to do anything but cook,” Holland said. “Ever since I was a boy, I only wanted to make great food.” And he certainly did.

Just a few days in Ludlow were not enough to even sample all the highly-rated bills of fare in this small town. The kitchens of the Olive Branch, Dinmore Hall Hotel, The Clive, Chang Mai, Fishmore Hall and the Michelin-starred Mr. Underhills, for instance, would just have to wait another visit.

Siân and I said our goodbyes, and I set out for North Wales. Tomorrow it would be back to fish and chips.

Comments