The beautiful coast of Dorset.NeedPix / Public Domain

Still far from madding crowds, Sandra Lawrence explores the countryside of Dorset.

Yes, knowing of the arrival of the new Far from the Madding Crowd film inspired my return this spring to the Thomas Hardy Countryside of Dorset. After all, it had been the original 1967 epic with Julie Christie, Alan Bates, and Terence Stamp that first introduced me to the imaginative landscape of Thomas Hardy’s Wessex, fictional yet amazingly real.

I first visited Hardy’s Dorset and Dorchester, the writer’s fictional Casterbridge, the epicenter of Wessex, in 1980. I stayed in a room over the old New Inn pub on South Street, the market town’s chief commercial thoroughfare. My “splurge” dinner of the week was in the dining room of the Antelope Inn, the room where the hanging Judge Jeffries famously conducted the Bloody Assizes. I walked quiet lanes surrounding the town to Stinsford church and to the enormous Iron Age hillfort of Maiden Castle.

Now, South Street is pedestrianized and chic, the New Inn was long ago replaced by an electrical supply shop; the Antelope Inn became a shopping arcade, and the countryside to Maiden Castle has been swallowed by the gleaming and still-expanding planned community of Poundbury. From an agricultural county town of 7,000, Dorchester (and Casterbridge) has mushroomed to a busy commercial center of 20,000 with an affluent, contemporary vibe.

It is one of Hardy’s dominant and recurring themes: the impact of time upon the timeless, in the lives of people and on the landscape. What changes, and what remains the same? In the tension of that question the boundaries between the real and the fictional overlap.

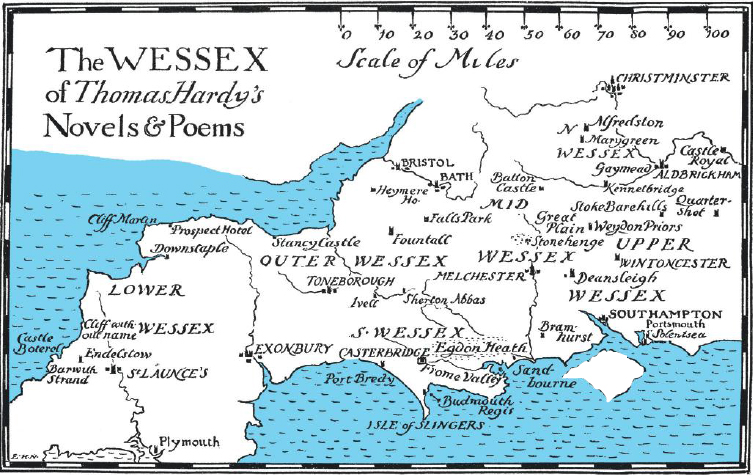

Thomas Hardy’s Wessex, the fictionalized landscape of his novels and poetry, stretches from its Dorset heart west to Devon and Exeter, east across Hampshire and north to Oxfordshire. There lies the oxymoron: the writer created a detailed map, with fictional place names, rivers, and landmarks—except it is the recognizable familiar landscape of southwest England, largely the West Saxon kingdom of Alfred the Great. Wessex is fictional in name(s) only.

The rural, agrarian mid-19th-century Dorset that was the backdrop against which Hardy’s memorable, often tragic, characters played in his Wessex novels and poetry remains visible today, surprisingly easy to experience.

Of all the great novels in the canon of British literature, Thomas Hardy’s can best be seen in their actual setting. Almost all of the scenes of The Mayor of Casterbridge, for example, are still recognizable in the Dorchester of today. I stayed at the King’s Arms Hotel, Casterbridge’s opening scene in the novel, where Michael Henchard, the mayor, held the chair at a banquet. Hardy himself as an older man used to come to town from his home at Max Gate to sit in the ballroom’s big bay window facing High East Street, take tea, write and people-watch.

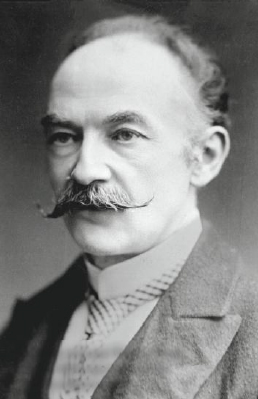

Novelist and poet Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) was awarded the Order of Merit in 1910. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Hardy lived his boyhood in the thatched cottage of his birth in the hamlet of Higher Bockhampton a few miles east; it was here he penned Far from the Madding Crowd. Dorchester was his hometown, though, with its surrounding countryside his strongly felt “home of the heart.” Hardy trained as an architect and lived in London for some years as a young man, and, as a newlywed, lived two years in the village of Sturminster Newton to the north. As soon as literary success made it possible, however, he returned to Dorchester in 1885, built a home to his own design on its outskirts, and lived out his life here (1840-1928).

The writer still has myriad fans and readers across the globe, who come to visit Dorchester and surprisingly find Casterbridge. A first stop at the Tourist Information office in central Trinity Street yields street maps and Hardy maps, and usually Hardy events or lectures in the offing. Then, literary pilgrims follow Hardy’s scenes around the ancient town.

At Top ‘o Town, literally the top of the rising High Street, a statue of Thomas Hardy commemorates the town’s most famous son and makes a good place to start. Right across the road, the Keep Military Museum celebrates 300 years of the Dorset and Devon regiments; in Hardy’s Casterbridge, it was the barracks of the swank Sergeant Troy.

Several maps of Thomas Hardy’s fictional Wessex were published in early editions of his novels. COURTESY THOMAS HARDY COLLECTION AT DORSET COUNTY MUSEUM, DORCHESTER, UK

Leading to the south, the West Walks has been a familiar tree-lined promenade from the days of Casterbridge to this. South Walks remain as well. They grew as paths following the line of Roman walls that encircled what was the Roman garrison town of Durnovaria. A single stretch of Roman construction remains not far from Hardy’s statue.

Near the coast in East Dorset, Corfe Castle has dominated the landscape since the days of King John. Dana Huntley

Outside the South Walks just a few hundred yards, the Maumbury Rings set a dramatic scene in The Mayor. What was once a Roman amphitheater capable of seating a legion, though, was old long before the Romans arrived. It dates from Neolithic times, as does the mighty hillfort Maiden Castle. The largest such Iron Age fortress in Britain was conquered by Roman invaders in 96 B.C., and the residents moved to the new Roman town of Durnovaria. To the east, Grey’s Bridge over the River Frome clearly marked the edge of town in 19th-century Casterbridge, and still does. East of the meandering river, the stretching meadows are pasturelands for grazing cattle land, and copses of woods bloom along the riverbanks and on rising ground.

For another bucolic look at how town and country meet, follow the footpath from Grey’s Bridge along the banks of the gentle, curvy Frome, still, the natural boundary defining the town, with the countryside and landscape virtually unchanged since Hardy described it. At the Hangman’s Cottage, footpath and river turn north toward Sherborne and disappear in the undergrowth.

Back at the town’s center point, the Corn Exchange and St. Peter’s Church were centers of community life for the denizens of Casterbridge. Just up pedestrian South Street, an impressive stone and brick Georgian townhouse house a branch of Barclays bank. A plaque next to the door identifies it as having been the residence of Henchard, the Mayor of Casterbridge. Next door to the church, don’t miss the Dorset County Museum. It’s an eclectic treasure of the town and county’s history: archaeology and pre-history, Roman and agricultural life, significant personages, and more. A large gallery is devoted to the life and work of Thomas Hardy, including manuscripts, personal effects, and a complete recreation of the author’s study from Max Gate.

The Georgian townhouse on South Street identified as Henchard’s residence is now a Barclays branch. Dana Huntley

From Dorchester, the towns and landscapes of Hardy’s Wessex radiate in all directions. To the south, it’s only six miles over the moors to seaside Weymouth, fictional Budmouth. Turn west along Chesil Beach, the Jurrasic Coast, to Bridport (Port Bredy) and Lyme Regis. Turn east toward Wareham (Anglebury) and visit the iconic Corfe Castle. After four centuries as a Royal powerbase, the fortress was taken and slighted by the Parliamentarians in 1646.

To the north a dozen miles through Cerne Abbas lies the pretty, quite olde-world town of Sherborne, Hardy’s Sherton Abbas. The “Abbas,” Sherborne Abbey remains impressive and active today. A number of recognizable scenes in Far From the Madding Crowd were shot in the abbey precincts and nearby narrow streets.

Sherborne’s other claim to fame is the presence of two castles: Sherborne Castle and Sherborne Old Castle. Both of these were the showcase homes of Sir Walter Raleigh. When the old place wasn’t big enough and grand enough, he built the fashionable new mansion just a short way across the river. Of course, shortly after that came his unfortunate fall from grace and power, and execution by Queen Elizabeth in 1589.

Horses and their riders cross this expansive rape field in Blackmore Vale. Dana Huntley

To the southeast of Sherborne, the broad Stour river valley of Blackmore Vale spreads some 20 miles to the trim Georgian market town of Blandford Forum. At the midpoint, Hardy’s one-time residence overlooked the mill at Sturminster Newton, open and operating today. It was here Hardy wrote The Return of the Native. He called the small town Stourcastle.

Blackmore Vale became the Valley of the Big Dairies, a particularly appropriate and recognizable moniker. This is fertile, arable farmland, and still supports large herds of Frisians who graze on sprawling stretches of rich pastureland. In the spring, broad fields of rape turn the landscape bright yellow.

Thomas Hardy’s created world resonates with a sense of place, and this is the place. Behind the contemporary town bustle of 21st-century life, Dorset is still an agricultural county at its heart—with a rural character defined by its limestone landscape over centuries. It’s the landscape that is eternal—Thorncombe Wood and Blackmore Vale, the watermeadows of the River Frome, Maiden Castle and the Maumbury Rings. Human lives will come and go, but the stage on which they play their part remains. No writer has evoked that any better than Hardy.

On the road:

Via the M3 and the A31 to the A35, Dorchester is a relatively easy two to three-hour drive from London. Dorchester can also be accessed by train via Southampton on the Weymouth line. All the tools for exploring Dorchester and Hardy’s Dorset can be found at www.visit-dorset.com.

In the neighborhood:

A few miles east of Dorchester on the A35 lies Tolpuddle, the village of the famous Tolpuddle Martyrs, and the Tudor manor of Athelhampton House.

Take a day trip from Dorchester, to seaside Weymouth. Then, follow Chesil Beach (the Jurassic Coast) west on the B3157, through Abbotsbury to Bridport, and return on the A35.

* Originally published in September 2015.

Comments