THE ALLIES SOLVED THE CRITICAL SUPPLY PROBLEM BY BUILDING THEIR OWN PORTS AND BRINGING THEM ALONG BEHIND THE ALLIED INVASION FORCES.

[caption id="ToNormandy_Feature" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© © HULTON GETTY

NO LESS THAN WHEN William of Normandy invaded England in 1066, the planners of the D-Day invasion in 1944 struggled with the enormous difficulties, not only of forcing

a landing upon a hostile shore, but also of amassing enough supplies to assure that they could maintain themselves once they had done so.

The nature of modern warfare made the challenge faced by the Supreme Allied Headquarters prior to D-Day much greater than those successfully overcome by the Normans nearly a millennium earlier. Not only did the Allies plan to land a much larger force in France than William had brought with him to England, but equipment and weapons undreamt-of by William would need to accompany them: 30-ton tanks and an assortment of other vehicles, bombs, ammunition, and fuel. Allied strategists estimated that their armies would require almost 30,000 tons of such materiel every day in order to sustain themselves and move off the beaches into the heart of Europe.

Logically, it seemed that there were two ways to deliver the goods: either the initial assault could be aimed against a major port that could then quickly be used to unload freshly arriving troops and supplies, or the assault troops could come ashore on a less heavily defended beach and then race to capture a port from the landward side. Both strategies entailed major risks. Knowing that the Allies could not exploit a successful landing in France without a port, the Germans had heavily fortified them. The disaster at Dieppe in 1942 showed that landing at even a small Channel port would be an extremely costly venture with no certainty of success.

The Germans had fortified northern France’s beaches far less heavily. But by landing on an isolated beach, Allied troops risked being hemmed in near the coast, unable to advance because only a trickle of supplies could come ashore without a functioning port.

Churchill had envisioned a solution to this dilemma as early as 1942. The invaders, he reasoned, would have to bring their own ports with them. The Prime Minister undoubtedly knew how absurd the idea must have seemed. He told his planners: “Let me have the best solution worked out. Don’t argue the matter. The difficulties will argue for themselves.”

The requirements were staggering. The British and Americans would need two artificial harbours to serve their designated invasion beaches. Each harbour needed to be roughly the size of the port of Dover and be capable of unloading 12,000 tons of supplies and 2,500 vehicles a day. And the harbours needed to be portable. But at least they did not need to be indestructible. The Allies targeted the French port of Cherbourg for early capture in order to ease the supply strain, so the artificial harbours were only expected to hold together for 90 days.

[caption id="ToNormandy_img1" align="aligncenter" width="1024"]

© CORBIS

[caption id="ToNormandy_img2" align="aligncenter" width="458"]

© MICHAEL ST.MAUR SHEIL/CORBIS

Each of the artificial harbours, called “Mulberries,” consisted of several components. A pier, secured to the sea floor but contrived so that it could rise and fall with the Channel tides, provided an off-shore anchorage where deep-draft cargo ships could unload. A chain of flexible floating roadway sections linked the piers to the landing beaches. A breakwater consisting of huge blocks of concrete three storeys tall protected the entire delicate supply unit from rough seas. Finally, blockships sunk nearer to shore provided sheltered areas where smaller landing craft could unload directly onto the beaches.

The enormity of the task is hard to imagine. The largest breakwater sections were 200 feet long and 60 feet tall, and upwards of 200 units were needed in all. Some 20,000 workers were employed in constructing the Mulberries, but the project was so secret that most of them had no idea what they were building.

[caption id="ToNormandy_img3" align="alignleft" width="317"]

© HULTON ARCHIVE

158 TUGBOATS TOWED THE FIRST ELEMENTS of the artificial harbours across the English Channel on the day after the initial landings, and by the fifth day of the operation the blockships had been positioned and sunk off the Normandy coast. By the 13th day both the American and British harbours were functioning, though not yet complete. They were already desperately needed. At the American beaches, for example, only about a third of the supplies necessary to sustain the invasion came ashore in the first two weeks. The harbours quickly made an impact, and the amount of cargo being delivered rose to a more manageable 75 per cent of the hoped-for rate.

As the last sections of the fragile floating roadways were towed across the Channel, a storm struck. The roadway sections sank almost immediately; the breakwaters themselves suffered a longer, more torturous pounding. The American Mulberry had been the more nearly complete of the two, but it owed this to the lesser degree of care its builders had shown in their rush to complete it. Under the battering of the storm-churned sea, it came apart after nearly three days of incessant pounding.

The better-built British Mulberry fared better, but it too suffered major damage and needed extensive repairs. This was accomplished by salvaging parts from the wreckage of the American harbour. Eventually, the Mulberry at Arromanches achieved a daily rate of about 9,000 tons of cargo unloaded daily, and it operated until the end of August, when the Allies began bringing supplies in through the captured French port of Cherbourg.

But while the Mulberry harbours proved to be a brilliant engineering feat, the role of a much more modest contrivance gets far too little credit for helping the Allies win the war of supply. The awkward looking DUKW amphibious truck, built by General Motors, proved so capable that many of the difficulties of landing supplies directly on the beaches, which had so concerned Allied planners, failed to materialize. In fact, the amphibious trucks outperformed the Mulberries and allowed the Americans, without their artificial harbour, to land more supplies than the British, whose harbour remained intact.

[caption id="ToNormandy_img4" align="alignright" width="316"]

© HULTON-DEUTSCH COL ECTION/CORBIS

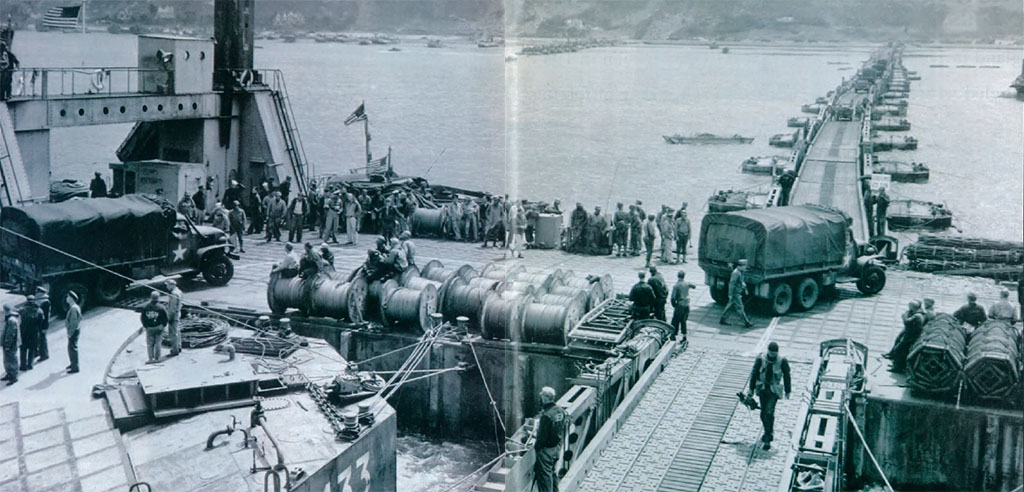

Another effort to ease the supply crunch produced less favourable results, but testifies nonetheless to the ingenuity of the Allied planners and their willingness to try anything to ensure the success of the invasion. Recognizing the amount of fuel that the mechanized Allied army would consume, and the vulnerability of ocean-going fuel tankers, military planners decided to lay an underwater pipeline across the Channel to deliver petrol directly from England to the coast of France. The three-inch-diameter flexible pipe was uncoiled from huge floating drums that tugboats towed across the Channel. While ultimately successful, PLUTO, an acronym for “pipe line under the ocean,” took so long to deploy that the invasion troops had already advanced several hundred miles inland by the time the fuel began flowing. While PLUTO delivered more than 100 million gallons of petrol, it became very much a secondary source, since by the time it began operation in September, major French and Belgian ports were in Allied hands.

Comments