Watling StreetGetty

Celtic traders trudged it and Roman soldiers marched along it, making Watling Street, stretching from Canterbury to Westminister, one of the most fascinating and historical routes across Britain.

The discovery last year of the original Roman coastline at Richborough, Kent, revealed for the first time the actual beach Emperor Claudius’ men crossed to claim the prize of Britain. After the Romans had managed to take over most of Britain, they built roads. And one of the most important led from the channel coast across the country diagonally to Viroconium, today’s Wroxeter Roman City. That was Watling Street.

The Richborough discovery made me curious to trace Watling Street, the Roman road that led northwest from there eventually to Chester and across North Wales to the Isle of Anglesey and Holyhead, then as now the port to Ireland. Much of its length today remains true to the route the centurions knew.

Roman City

Watling Street

Study the map and it is clear that modern-day Watling Street neatly divides into two convenient sections. From the coast at Dover to London, it is the A2 sometimes called the Great Dover Road. From London, the A5 follows Watling Street north to its original end in Wroxeter, just outside Shrewsbury.

Like occupiers through the ages, the Romans quickly adapted the infrastructure of the colonized and built their street on long-established routes. The street has two acknowledged starting points: Dover, the site of Rome’s arrival in A.D. 43, and Richborough, just a few miles north along the Kentish coast. It strides off into some of England’s most beautiful countryside, drenched with its bloody history—passing Canterbury, where an enraged English King made a bloody martyr of a tiresome priest; through the idyll of Kent into the gaping metropolis of London, along the Old Kent Road (the cheapest square on the British monopoly board) to the Edgeware Road.

Watling Street

Towcester

Plan to take two days to travel along Watling Street. Leave the south coast and stay over in or around Towcester, the ancient Roman fort of Lactodurum, which is a convenient halfway point.

Follow the road out of London to St. Albans, where a Roman centurion paid the price for following the new religion and where Ye Old Fighting Cocks, which claims to be Britain’s oldest pub, sits among some of the country’s most expensive real estate. The road then marches past the exotic lions of Woburn until it arrives in the modern city of Milton Keynes.

Allowing a day to travel to Towcester means that should something look intriguing there is time to side-step the timetable. Canterbury Cathedral, Rochester Castle, Woburn Abbey and the WWII spy center at Bletchley Park are just some of the sites along the way. The presence of the Silverstone motor racing circuit means there is no shortage of comfortable and luxurious hotels and more basic B&B accommodations in the Towcester area.

I planned to drive the northern half of Watling Street and called my friend Peter Dunkley, a man with an intimate history with the old road. Peter lives in an 18th-century farmhouse just 150 yards from the A5 and little more than six miles from Towcester.

Canterbury Cathedral

Heading Northwest

“Do you want to make the road trip in a classic Land Rover?” Peter asked. “It’s a military road so what better to use than a military vehicle?” His 1967 Land Rover has seen better days. Its mileage is impossible to determine as the numbers have gone around the clock too many times. We rendezvoused at his house and set out to explore Watling Street’s northern stretch. But before we tackled the tarmac, there was a more pressing concern: lunch.

We set off for Jack’s Hill Café to take on an all-day full English breakfast. Though the café has been a favorite with Peter for more than 30 years, this was the first time I had stepped across Jack’s doorstep. This is a truckers’ café; the food is basic, unashamedly English with no nod to fashionable Mediterranean cooking except for the canned Italian tomatoes. The fare is prone to give a cardiac specialist sleepless nights. Truckers’ cafés like Jack’s are a throwback to a pre-expressway age when trucks were smaller, loads lighter and long-distance trucking followed the Roman roads.

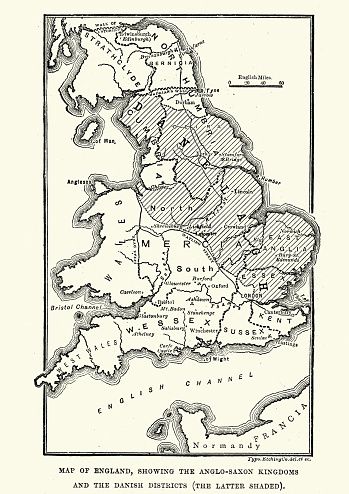

Danelaw: Don’t pay the Dane

In the 9th century, Watling Street was more than just a route through the English countryside. It was a border between those parts of England that had been invaded and colonized by the Danish and those that remained in the control of the Anglo-Saxons. The Treaty of Wedmore saw the beaten Danes withdraw to an area North and East of Watling Street north of London. Its law ran in these areas, hence the name Danelaw.

A dark, brooding presence, the Danes agreed not to invade the Anglo-Saxon areas if a ransom was paid. This blackmail acquired a name: Danegeld. The phrase ‘paying someone Dane-geld’ has become so associated with Rudyard Kipling that it is often attributed to him, even in books of quotations. He is certainly responsible for its entry into everyday language but he did not actually invent it. The phrase had long been used to describe anyone—especially a national leader—who chose to take an easy way out of a problem rather than face up to the more difficult task of solving it once and for all. As Kipling warned,

“… if once you have paid him the Dane-geld You never get rid of the Dane.”

Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms and the Danelaw

Real ale awaits

We arrived in Shrewsbury, Shropshire’s medieval county town. Shrewsbury has a major range of accommodation; from high-end hotels to B&Bs. This year, the town is enjoying a year-long celebration of the bicentenary of the birth of native-son Charles Darwin. Events run to November and are expected to draw thousands of visitors.

While Shrewsbury is not the official end of Watling Street, it certainly felt that way as we eased out of the car. Having arrived as dusk was falling, we missed out on the famous medieval charms of Shrewsbury. What we did not want to miss were some liquid refreshments.

With a thirst for real ale and no knowledge of the city, some initiative was called for. “Are you local and do you know a decent pub?” I asked a passing traffic warden. “It cannot be a chain pub.” The traffic warden directed us to the Coach and Horses on Swan Hill.

The bar was snug; the gas fire burned brightly as the pub filled up. Pints of Wye Valley’s Golden Pale Ale were quickly given over by the barman. Having to drive back to Peter’s that night, we left Shrewsbury with a heavy heart, not least for missing out on the pub evening promising the best Shropshire fare including almost every form of game.

Shrewsbury

A six-day walk

I stood Peter lunch the next day at The Saracen’s Head in Towcester, a three-star hotel with an impressively long ironstone frontage directly on the A5. Charles Dickens’ readers might recall the name from The Pickwick Papers. In what is possibly one of English literature’s earliest product placements, Dickens wrote that Pickwick meets an old acquaintance at The Saracen’s Head. At the time, Watling Street was the key stagecoach route between London and Holyhead for services to Ireland, and the inn offered overnight accommodation.

It would be nice to report that the hotel maintains a suitably Dickensian atmosphere, but the march of time has removed anything that Pickwick might have recognized. The lunch was barely a triumph of modern British catering, but the beer was decent and that made it all right. It was with pleasure that we realized we had traveled in one afternoon the distance a Roman expected to walk in six days.

Even if you do not have the noisy, character-building discomfort of a 1960s Land Rover to travel along the Watling Street, do not travel the route as keen students of Roman history looking for evidence of Roman Britain. In the 2,000 years since engineers plotted its route across England, it has remained a working road that takes you into the heart of modern England. Each era has widened, resurfaced and removed Roman artifacts, making it truly a route from Roman Britain into the 21st century.

Watling Street

* Originally published in 2016, updated in 2023.

Comments