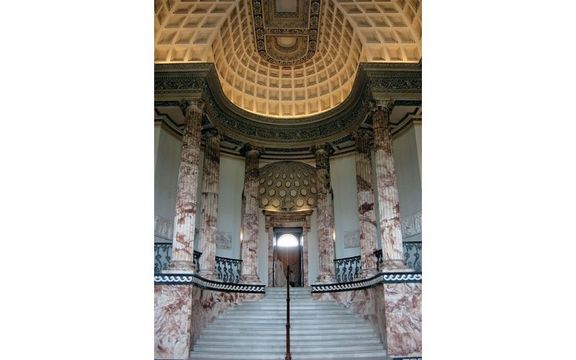

A 50-foot high apse ceiling crowns the entry hall of Derbyshire alabaster at Holkham Hall.

Viscount Tom Coke, heir to the Earldom of Leicester, on his life running, and the history of Holkham Hall in Norfolk.

How does one address a viscount? The intricacies of the British peerage troubled me as I traveled to Holkham Hall, the center of a 25,000-acre estate in north Norfolk, to visit with Viscount Coke, heir to the Earldom of Leicester. I needn’t have worried. I was greeted with a friendly smile and the instruction: “It’s the 21st century—call me Tom.”

Like his illustrious ancestors, Tom Coke manages a vast agricultural estate, and enjoys welcoming visitors to his home.

Tom, or Lord Coke for those who wish to keep things formal, belongs to an aristocratic lineage 400 years in the making. The founder of the family fortunes was Sir Edward Coke, a Norfolk-born gentleman who became the foremost legal mind of the Elizabethan and early Jacobean era. He coined the phrase “an Englishman’s home is his castle,” and as attorney general he prosecuted Robert Devereux, Walter Raleigh and the Gunpowder Plotters. He also managed to gather enough wealth to purchase the Holkham estate and build a small home on it.

Read more: Cruising Coastal East Anglia

That passed down through the generations until, more than a century later, his descendant Thomas Coke went on the longest recorded Grand Tour of Europe. Thomas was away for six years, accompanied by a tutor from Christ’s College Cambridge, who advised his charge on buying libraries, works of arts and sculptures. The current Lord Coke has just discovered that “it was a tossup for the trustees between sending him on a Grand Tour or to Oxford University. I’m very glad that they chose the Grand Tour!” That’s because young Thomas returned with a head brimming full of ideas and started building a new house to accommodate his continental collections in 1734. The impressive result was Holkham Hall, a place that the Lord Coke and his family still call home.

Holkham Hall is the fulcrum around which the Holkham estate sprawls, “the jewel in the crown,” according to Lord Coke. The country house, a masterpiece in the Palladian style, was the product of Thomas Coke’s singular vision. First impressions count, and the Marble Hall must be the most spectacular entrance hall in the world. The lower walls are faced with a layer of Derbyshire alabaster, not marble as the name suggests. A screen of columns hides the classical statues on the first floor, which can be reached via a shallow staircase. It is all crowned by a 50-foot high apse ceiling.

Leading from the Marble Hall are staterooms, bedrooms, galleries and libraries. “The whole of the central block is open to visitors,” Lord Coke reveals, “also part of the first floor of the stranger’s wing, the three libraries in the family wing and the kitchen wing. It all flows very easily.”

The rooms are adorned with the stunning artifacts that Thomas Coke brought back from the continent. The gallery is home to a set of antique statues from Rome, often procured from shady dealers only too happy to sell an ancient civilization’s finest treasures at the right price.

Dotted around the walls are typically aristocratic portraits of Lord Coke’s ancestors, joined by a host of other paintings, often with Biblical or classical subjects. A whole room is set aside for landscape paintings, still arranged in the order decided by Thomas Coke. These fine art objects are a particular passion of Lord Coke, who studied the history of art at the University of Manchester.

A train of visitors plodding through your house must be odd, but as Lord Coke says, he has plenty of space. “The house is large enough that I could spend the whole day in it without knowing that there are visitors here, too,” Said Coke. “Having said that, I really enjoy having people here and I try to nip out once a week to chat to the room stewards and visitors.”

SCOTT REEVES

Lord Coke moved into the house in 2007 after his parents decided to retire to a smaller house on the estate. “Dad moved out of his own volition, which was very enlightened,” he said. “My son will hopefully inherit and live here after me, and may live in this house for as long as my father and I combined. Hopefully, he will grow to love it even more than we do.”

And that is the special appeal of Holkham Hall. Britain is lucky to be awash with country houses, stately homes and historic ruins. Many of them are in the care of English Heritage or the National Trust and seem dead, frozen in time, a relic of past years. But Holkham Hall is a living, evolving home, and Lord Coke knows that this does not go unnoticed. “We get a lot of nice comments in the visitor books from people who pick up on the fact that the house is lived in,” Coke said. “It might be our cars parked on the terrace, or a children’s football or bicycle parked on the grass, or modern photographs dotted around the house or our dogs running around.”

Reconciling the heritage in a Georgian country house with the modern life of a young family necessitates a few changes behind the scenes. “English Heritage are very sensible and realize that houses like this must continue to be lived in and evolve,” Lord Coke explains. “We live in the family wing with four children; so we have five bedrooms, a playroom, a kitchen-diner, some bathrooms and my wife’s office. There is no sitting room, but in the evenings I sometimes go and sit and read in one of the libraries.”

And would a nosy visitor peeking around notice the difference between the old Holkham Hall and the new, modern parts? “Well, we did invite a friend for dinner soon after we moved in,” Lord Coke laughs. “He looked at the kitchen-diner and announced, ‘it’s just like being at a house party in Fulham!’”

Modernization is something that goes beyond the walls of the house. The Holkham estate is now a thriving organization, but it was not always so. Just after World War II, the Coke family opened negotiations with the National Trust about bequeathing the property to the nation and relinquishing the cost of maintaining it. That is no longer on the cards; the last couple of generations have made the estate self-sufficient.

Aware of the need to improve the visitor experience, Lord Coke and his father spearheaded the expansion and diversification of Holkham as an attraction. Now the estate makes much of the Bygones Museum hosted in the old stable block, the National Nature Reserve at the beach, and the gardens that host classical concerts and a bi-annual country fair. Visitors can extend their stay at the Victoria Hotel, Pinewood Country Park or nearby Globe Inn, all of which are managed by the Holkham estate.

“People associate Holkham with quality,” Coke said. “We employ excellent, top-caliber people to help us manage the estate in the most professional way. That’s not necessarily the most commercial way. For example, I want to clean all the paintings and re-gild areas where generations of fastidious cleaning ladies have worn down the gold leaf.”

I expected that opening up Holkham Hall was a relatively new phenomenon, born of a need to pay the bills. It is actually a long tradition. “The house has always been open to the public; it was built for show,” said Coke. “The first Thomas Coke opened it for a day a week. He wanted to say ‘look at what I have achieved, what I have bought, am I not an erudite man?’”

SCOTT REEVES

Another family tradition dates back generations—that of leaving the Holkham nest to go out and gain life experience. Thomas Coke did it on his six-year Grand tour, the present Tom Coke did it with six years in the Scots Guards. “You can get very insular if you spend your whole life in a place like this,” Lord Coke admits.

Yet when he considers everything, Lord Coke is in no doubt that he would have it no other way. “Living here is a positive experience. My wife is very down-to-earth and I worried that she would prefer the farmhouse that we used to live in. But within a month of moving here she turned to me and said ‘it feels like home.’”

Indeed it does. Holkham Hall is a rare breed, a historic country house that doubles up as a family home, exuding a warm, welcoming atmosphere.

Our visit over, Lord Coke is quickly back to the chores of daily life. His dog, Shrimp, needs to go to the vet. I overhear a portion of the telephone conversation while I pack away, a cute juxtaposition of Georgian and modern Britain: “My name is Tom Coke… My address? Holkham Hall.”

Read more: At home with the Wesley brothers in Epworth

* Originally published in Jan 2012.

Comments