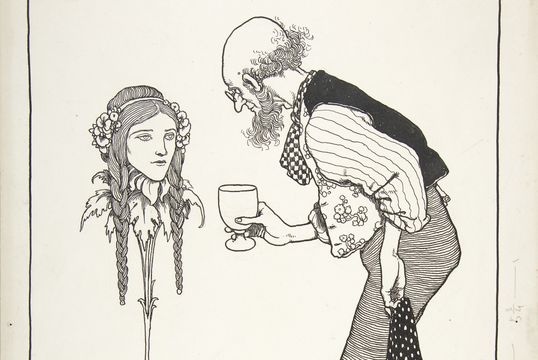

"Hitherto I Have Performed it Myself": Six Dead Secrets, Topsy-Turvy Tales, by William Heath Robinson. The Met / Creative Commons

The life, work and death of William Heath Robinson, best known for drawings of whimsically elaborate machines to achieve simple objectives.

In the United Kingdom, they were Heath Robinson contraptions. (In the U.S. similar gizmos came to be known as Rube Goldberg machines.) Seldom does an artist’s style and imagination prove so inventive that existing adjectives prove simply inadequate, so that the artist’s own name is the only suitable description of his work.

Read more

In William Heath Robinson’s case, his name became synonymous with any overly complicated device designed to execute the simplest of tasks, and which no one in his right mind would ever actually consider building or using—but which, for all that, really could work (probably), although only with an unwarranted investment of labour. But such a description, you see, is no less cumbersome than one of these machines itself. So much easier1to just call it what it is—a “Heath Robinson.”

William Heath Robinson was born on 31st May 1872 and, along with his two brothers, seemed destined to follow in his father’s line of work. Thomas Robinson worked as a wood engraver, creating illustrations for newspapers and periodicals. The late 19th century, however, would see the decline of the wood engraving trade, as more modern printing technologies supplanted traditional techniques. What’s more, young Will had loftier dreams. Rather than the more settled life of a hard-working commercial artist, he envisioned himself leading the more glamorous existence (so he thought) of a classical painter. “It was only a matter of choosing whether I should paint frescoes in cathedrals or monasteries, or whether I should wander all over the world painting mountain scenery or old cities …,” he later noted whimsically.

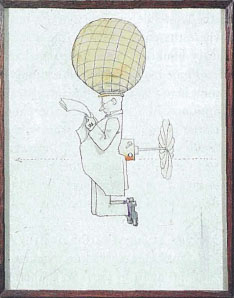

“The Personal Aerial Travel System for Gentlemen,” one of the simpler of Robinson’s “inventions.” BONHAMS.LONDON.UK/BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRART

His parents enrolled him in the Islington School of Art, and, fueled by his soaring ambition, he succeeded in gaining admission to the Royal Academy in 1892. But by his own admission his work did not compare favourably to that of some of his classmates. By 1897, when it became necessary for Robinson to begin earning an income, he realistically decided that “so few people wanted their portraits painted,” and “nearly all the churches were already decorated.” After a short and unsuccessful attempt at establishing himself as a landscape painter, Will reconsidered commercial art, a line of work his brothers had already embraced.

Within a short time Will, sometimes in collaboration with his brothers, had received commissions to illustrate editions of Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, The Pilgrim’s Progress, Don Quixote, Arabian Nights and other popular titles. In 1902 he succeeded in selling his publisher on an idea for a book of his own, The Adventures of Uncle Lubin, which he illustrated himself.

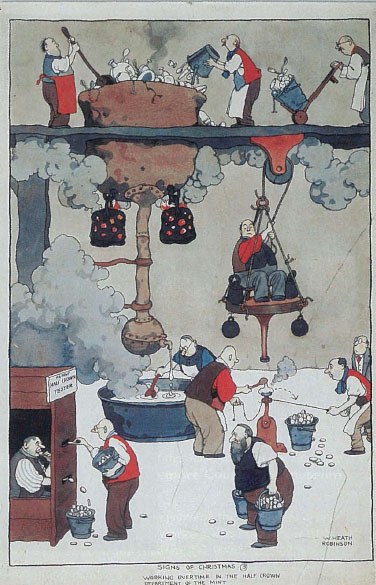

“Signs of Christmas” depicts mint workers making new half crowns. CHRIS BEETLES LTD LONDON UK/BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

Although he remained somewhat in the shadow of his contemporary, Arthur Rackham, Robinson built a solid reputation. His fortunes suffered, though, when his publisher, Grant Richards, went bankrupt, leaving Will unpaid for 254 black-and-white illustrations, and without an outlet for his work. In need of some quick income, he turned to comic drawings that he could sell to newspapers and magazines. This genre would eventually become the one Robinson is most strongly remembered for, but his eccentric sense of humour initially left publishers more bewildered than amused.

Ironically, the event that may have done more than anything else to establish Robinson as a comic genius proved to be the Great War. There was precious little about life and death in the trenches to laugh about, but somehow Robinson culled humour even from such an unlikely source. “The much-advertised frightfulness and efficiency of the German army, and its many terrifying inventions, gave me one of the best opportunities I ever enjoyed,” he remembered. And his success at lampooning the enemy proved a great boost to the morale of the front-line troops.

Many of Robinson’s war-time cartoons featured primitive incarnations of the contraptions that later made him famous. Satirizing the pre-war fear of German deviousness and technological know-how, Robinson depicted the enemy’s employment of a wide range of improbable “secret weapons,” from the Tommy Scalder, designed to dowse British troops with hot water, to the diabolical “Tatcho Bomb,” which demonstrated how hair tonic could be employed as an offensive weapon.

Heath Robinson at work, surrounded by examples of the many genres in which he achieved success, including a cover for Nash’s magazine.HULTON/ARCHIVE

If Will’s cartoon of a German officer poorly disguised as Father Christmas, leaving bombs in the stockings of sleeping British soldiers, seems a little grim in retrospect, to Robinson and the soldiers themselves it was all in good fun: “I believe that our sense of humour played a greater part than we were always aware of in saving us from despair during those days of trial,” he later wrote.

‘THE MUCH-ADVERTISED FRIGHTFULNESS AND EFFICIENCY OF THE GERMAN ARMY, AND ITS MANY TERRIFYING INVENTIONS, GAVE ME ONE OF THE BEST OPPORTUNITIES I EVER ENJOYED’

The outbreak of peace in 1918 put an end to this great opportunity for comic expression, but it also allowed him to expand his work into a different arena. Between the World Wars he was highly sought-after by manufacturing companies to design their advertisements and brochures. Johnny Walker whisky, Mackintosh Toffee, and many other firms featured his work, and one, Newton Chamber, Lid., went so far as to print his artwork on its Izal Medicated Toilet Paper.

During these inter-war years, his trademark “contraptions” came to full flower. Pen-and-ink drawings like “An elegant and Interesting apparatus designed to overcome once and for all the difficulties of conveying green peas to the mouth,” and “A convenient magnetic contraption (with mirror attachment) for reducing the figure. Recently placed on the market,” soared to new heights of comic absurdity.

The Britain of the 1930s grew increasingly industrialized, congested, and mobile, and many social commentators looked upon these trends with a wary, even disapproving eye. But while pessimists viewed this brand of progress as dehumanizing and decadent, Robinson’s illustrations seemed to hail humankind’s innate ability to cope. Much as his wartime cartoons had drawn humour out of suffering, his series “How to Live in a Flat,” “How to be a Motorist,” and “How to be a Perfect Husband” provided satirical insights into overcoming the many challenges of modern life—how, for instance, to enjoy the pleasures of a garden when you live on the top floor of a multi-storey building.

As might be expected, the rise of Nazi Germany and England’s declaration of war in 1939 prompted Robinson to take a fresh look at the military potential of his contraptions. His satires of Hitler, Goring, and the rest of the Nazi party bigwigs, including the decidedly disrespectful illustrations done for R.F. Patterson’s parody, Mein Rant, earned Robinson a place on a Nazi list of civilians to be arrested should Britain fall to invasion.

Robinson may have grown a bit wistful about his own popularity, which had diverted him from his dream of becoming a serious artist and left him “type-cast” as simply a jokester. This seemingly inescapable fate might have inspired his 1920 sketch for The Bystander, titled “A Heath Robinson drawing of Heath Robinson drawing a Heath Robinson drawing.”

His final act amounted to the last commentary on the marvels of modern living, which he so often satirized. In September 1944 he underwent exploratory surgery in anticipation of a more extensive operation on his prostate. He returned home with tubes and catheters attached to his body and feeling in all likelihood like one of the unwieldy machines he had so often created. Apparently thinking it an undignified fate, he pulled out the tubes and quietly died.

It may be incorrect, though, to presume that Will’s quirky artistic style does not continue to influence the world. Following his death, his son, a Benedictine monk, presented copies of two of his father’s how-to books, How to Build a New World and How to Make the Best of Things to Pope John Paul II, who willingly added them to the Vatican’s library.

* Originally published in July 2016.

Comments