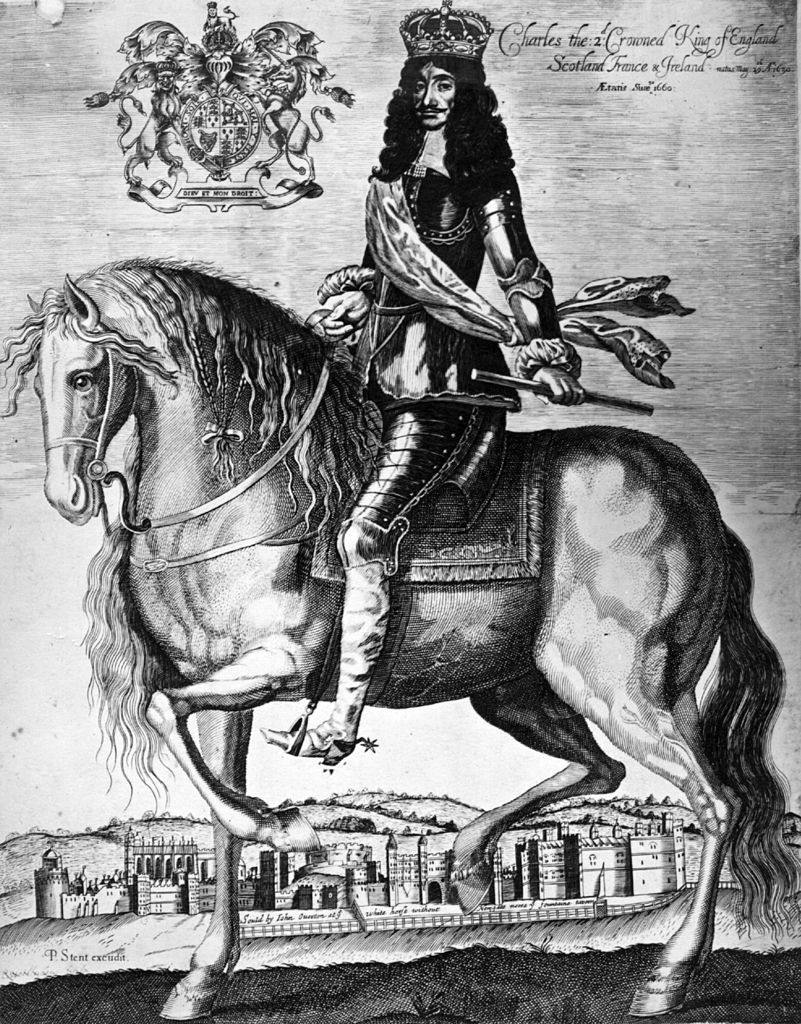

King Charles II Getty

The Merry Monarch kept the royal show on the road. Charles II was a polarizing figure. How much do you know about the former King?

Was the Restoration period of English history a tragedy or comedy, or both? The Merry Monarch who took the lead role for this Act, in the performance that was the House of Stuart, still divides opinion 350 years after he was restored to England’s throne.

From the drama of regicide to the bedroom farce of royal mistresses, Charles II stepped the boards with élan. Even on his deathbed, he was reluctant to vacate the stage, playing to the audience with, “I am sorry, gentlemen, for being such an unconscionable time a-dying.”

King Charles II

Charles' reign

Some commentators have called Charles’ reign the worst in English history. That’s too harsh a judgment on a man who kept the royal show on the road when kings before and after him so spectacularly derailed. He at least survived the stage traps of religion and power struggles with Parliament. And he gave us a dazzling interlude whose fruits can still be enjoyed today.

Both Charles’ grandfather James I (VI of Scotland) and father Charles I had displayed overconfident contempt for Parliament. Charles I, of course, lost his head in 1649 following the bitter civil war. Charles junior, born May 29, 1630, and just 12 years old when the Roundhead-Cavalier skirmishes kicked off, took part in the fighting. He was in exile in Holland when news came through that his father had been executed; he rushed sobbing to his chamber.

In an age when most people still believed that kings ruled by Divine Right, this regicide was shocking. Glimpse, though, the mettle of the new claimant to the throne: Charles set about engineering his return, throwing in his lot with the Scots who crowned him king in 1651. The price of the deal was that Charles swore to uphold the Scottish Covenant and impose the Presbyterian faith on his other two kingdoms, England and Ireland. It was a disingenuous deal that would never have worked, but Charles, devious and pragmatic, was biding his time.

Meanwhile, in England, Oliver Cromwell and his Parliament had abolished the monarchy. Charles marched south with an army and was soundly defeated at Worcester, September 3, 1651—visit the city’s Commandery, the former Royalist HQ, for a stirring account of the route. Drop into Boscobel House in Shropshire, too, where the Catholic Penderel family concealed Charles during his flight. As Parliamentarian troops scoured the countryside he famously hid up an oak tree before escaping into exile: All part of the romantic aura that would surround his return.

Maverick

While the Commonwealth government of the interregnum (1649-60) stamped its Puritanical weight on England, Charles combined happy-go-lucky philandering in Europe with continuing resolve to claim his crown. Towering well over 6 feet tall, with dark curly hair, he cut a striking figure, and his familiarity—his “common touch”—endeared him to all he met. By 1649 he had already sired James, future Duke of Monmouth, by one of his mistresses: He would have at least 16 illegitimate children by eight different lovers, unfortunately, none of them his Queen, Katherine of Braganza, whom he married in 1662.

When Cromwell died in 1658 and his son Richard proved unequal to taking over, England was ready to give royalty another try. Charles entered London on his 30th birthday in May 1660 amid joyous scenes. What did people expect? Release from 11 years of Puritan austerity, a return perhaps to partying, to sports and theater that had been proscribed. The Merry Monarch did not disappoint.

Charles' lifestyle

Just look at the sensual portraits of Restoration beaux and courtesans by Sir Peter Lely for a flavor of the racy new regime. Charles reveled in the limelight. He re-established and patronized theaters, and had a ready eye for the actresses, too: Nell Gwyn was his most famous mistress. He loved sports, particularly horseracing, and established the course at Newmarket in 1667—he even raced there as a jockey in 1675 and won the Twelve-Stone Plate. His nickname, Old Rowley, was taken from a stallion in the royal stud.

But the court’s loose morals and extravagant lifestyle soon caused a public scandal. As early as August 1661, the diarist Samuel Pepys was commenting on “the lewdness and beggary of the court, which I am feared will bring all to ruin again.”

At the same time, Charles’ tolerant, libertarian spirit allowed the arts and sciences to flourish anew. Dryden, Etheredge, and Sedley penned their witty, immoral comedies that tickled the King’s fancy. The masterpieces of Bunyan and Milton, Pilgrim’s Progress and Paradise Lost, chimed less with the spirit of the age, but the authors at least enjoyed free rein to express themselves.

Nell Gwyn

Scientific advancements

Charles’ passion for science translated into the patronage of the Royal Observatory at Greenwich under the first astronomer-royal, John Flamsteed. He also set up the Royal Society in London in 1660 with a view to “improving Natural Knowledge.” Isaac Newton formulated his theories on gravity; Robert Boyle steered modern chemistry out of ancient alchemy; Richard Lower performed the first blood transfusion between animals and Edmund Halley correctly predicted the return of the comet that bears his name. It was the birth of a scientific reformation.

After plague and then fire ravaged London 1665-6, Charles appointed Sir Christopher Wren as “Surveyor-General and Principal Architect for rebuilding the whole city.” Can you imagine the capital today without the magnificent St Paul’s Cathedral? Admire, too, Chelsea Hospital and other highlights of the age, like Wren’s sublime Sheldonian Theatre, Oxford.

Tensions appear

However, the Restoration was not all rave reviews. Religious conflicts unleashed by the Reformation, and the Tudor oscillations between Roman Catholic and Anglican rule, had never been resolved. Relations between king and parliament also remained uneasy. By the Declaration of Breda 1660, laying out the terms of restoration, Charles had pledged to uphold the Anglican Church but allow religious tolerance. Yet many in Parliament were distinctly intolerant, and that served only to push him back toward Catholic sympathies nourished on the Continent. His mother, wife, favorite sister, and brother James were all acknowledged Catholics; there were rumors that Charles had secretly converted, too.

Parliament feared—increasingly as the royal marriage failed to produce an heir—that a Catholic might yet bag the throne. Matters came to a head when Charles was forced to agree to a Test Act (1673) excluding all Roman Catholics from public office. Three times between 1679 and 1681 he thwarted Parliament in attempts to pass an Exclusion Bill that would debar his brother from the Crown: Charles’ habit of dissolving Parliaments unsatisfactory to his wishes brought back unhappy memories of his father.

Religious tensions were further inflamed by the hoax Popish Plot (1678) that warned of an imminent Catholic rebellion to put James on the throne, and the real Rye House Plot (1683) to murder Charles and crown his illegitimate son, the Duke of Monmouth. Over 35 Catholics were executed on trumped-up charges during the first frenzy, and the notorious Judge Jeffreys ruthlessly carried out Charles’ revenge on conspirators and other royal enemies following the second.

YALE CENTER FOR BRITISH ART, PAUL MELLON COLLECTION/THE BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

Things go south

Behind the scenes Charles had been striking covert deals with England’s old enemy, France: In return for much-needed money that Parliament failed to provide him, he had agreed to openly declare himself Catholic and, using force if required, impose his will on his country—all at some unspecified future point. France helped finance Charles’ wars with the Dutch in an ongoing battle for maritime and trade supremacy. Two treaties had concluded the financial arrangement: A secret one and another that was shown to Parliament’s Protestant ministers, the latter omitting all reference to Charles’ conversion. Had the duplicity leaked out, civil war would have ensued. Ever the consummate actor, the King successfully dissembled. But was the puppet master Stuart or French?

When things went wrong, Charles made scapegoats of his ministers. His mentor, the Earl of Clarendon, took the blame for the unpopular Dutch war; the King also deceived and used his five advisers known as the Cabal. It was Clarendon’s son, Laurence, First Lord of the Treasury, who nicknamed Charles the Merry Monarch. He also quipped, “He never said a foolish thing and never did a wise one.” The King delivered a double-edged riposte, “My words are my own, and my actions are those of my ministers.”

There was, however, one admirable headline from Parliamentary entanglements: The 1679 Act of Habeas Corpus, protecting the individual’s freedom from unlawful imprisonment—one of the country’s most significant pieces of legislation. It was rumored at the time that it only succeeded because lords in the Upper House amused themselves by counting an exceedingly corpulent member as 10.

Charles' legacy

Charles II succumbed to a stroke, February 6, 1685, aged 54. He died in the Roman Catholic faith. Although he had failed to beget a legitimate heir, he left a near-absolute, solvent monarchy. England was enjoying peace while other European countries were at war; her seamen were building an Empire; the arts and sciences were in robust health. The criticisms remain that Charles was unprincipled, prepared to sell his country and his religion to the French; he ducked and dived.

But consider the alternatives: His father Charles I’s haughty principles set him on a collision course with Parliament. Charles II’s successor, Catholic James II, equally arrogant, would be ousted in the Glorious Revolution. Stuart encores to regain the throne would fail in two Jacobite Rebellions. Old Rowley alone kept extremist factions around him at bay, and throughout his reign retained his popular, common touch. To this day the image of the Merry Monarch plays well to the gallery. He was neither a good nor an excessively bad king. The real question is—would the monarchy have survived had a different Stuart been restored to the throne?

Charles II

* Originally published in 2016.

Comments