In the crypt of ancient Whithorn Priory lie the bones of the Celtic missionary St. Ninian—among the first men to bring Christianity to Scotland. Inset: A rusting anchor rests in the Whithorn sun.Chris Sharp

From the archaeological wonders of St. Ninian's priory to Scotland's book capital - a journey of exploration and education.

Soft swirling mist obscured my view of the archaeological dig, as water droplets condensed on my spectacles. The archaeologists were gray figures shifting in and out of focus, as the vapor wove about them. They were like apparitions from the past, into which they were painstakingly delving, slowly exposing skeletons and artifacts with their brushes and trowels. Skeletons. A chaotic jumble of real skeletons. This excited my youthful imagination—a thrill that was heightened when an archaeologist invited me to brush away earth from the remains of a 10th-century man.

That was several decades ago; now I stand, in the early morning sun, surveying the former excavation site. The archaeologists’ trenches are filled and covered by close-cropped grass that is spiked with wooden staves outlining a Northumbrian burial chamber. Several information plaques summarize the dig’s findings regarding the ecclesiastical community that flourished here at Whithorn, in southwest Scotland. The plaques, though, give scant information about one of the dig’s objectives: to learn more about St. Ninian.

Exactly who Ninian was is a mystery. There are few written references to the saint, and those are not from his contemporaries. Some sources say he was born of noble parents, on the banks of the Solway Firth, in AD 360. The Venerable Bede described Ninian as “a most reverend and holy man of the British nation,” in his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written in AD 731. This statement places Ninian’s origins anywhere in the British-Celtic world of Cornwall, Wales, southern Scotland or Ireland.

Research compounds the mystery by proposing that St. Ninian was in fact St. Finian; Ninian being a corruption of the Irish saint’s name.

Ninian was certainly educated in Europe, and “had been regularly instructed at Rome,” according to Bede. He spent some time at Martin de Tours in France and returned to Britain with the expressed mandate to take Christianity to the southern Picts. For the proselytization of the Picts, he established a ni at Whithorn in AD 374.

As Ninian’s evangelical work radiated out from Whithorn Priory, the town became known as the cradle of Scottish Christianity. This surprised many visitors, who frequently associate Scottish Christianity’s origins with Colomba’s Abbey on Iona. When Colomba founded the Iona monastery, Whithorn had been established for 166 years and was a recognized place of pilgrimage and a center of Celtic education.

Leaving the small graveyard, where 1,500 graves have been excavated from a total exceeding 4,000, a small path rises to the remains of Whithorn’s medieval cathedral. Historians believed that Ninian’s original church was constructed solely of timber, until excavations in the 1980s unearthed lime-washed stones, dating from the 7th and 8th centuries.

This intriguing discovery threw light on several obscure references to Whithorn. Ptolemy, the Greek geographer, refers to a place in southwest Scotland called Leukophibia—“Shining Place.” St. Ninian’s church has historically been referred to as Candida Casa, which has been translated as White House or Shining Place. Confusingly, St. Ninian has also been referred to as “the shining light of the north.” In the 8th century, the Northumbrians translated Candida Casa into their own tongue as Hwit Aerne (Wit Herne), which has been corrupted into the modern Whithorn. Lime-washed stones shine brightly, as is beautifully attested by the picturesque, whitewashed cottages that dot the Galloway countryside today.

Now, all that remains of the medieval cathedral is the ruined but still splendid nave, which is hemmed in by a plethora of toppled and decapitated, ivy-shrouded and lichen-crusted gravestones. The cathedral was built upon the shrine of St. Ninian, which from the 5th century onward, for 1,000 years, was a place of pilgrimage.

The roofless nave is a glorious hodgepodge of ecclesiastical architectural styles that reflect the evolving needs of a thriving church whose walls were constantly shifted and reassembled over the centuries—evident along the nave’s south wall. The nave’s base is a stringcourse of 12th-century sandstone. At the east end is a doorway constructed of 15th-century arches over 13th-century arches, which have been inserted into the 17th-century wall, probably done to accommodate the rising ground level outside the church—growing approximately 75 centimeters over the course of five centuries. A doorway in this position would have been perfect, too, for the officiating priest’s entrance into the Episcopalian cathedral.

Beyond the 13th-century wall, buttressed to strengthen it as the church was extended westward, is an exquisite 12th-century doorway of decorated stone. That, too, is not what it seems: The arches were originally the cathedral’s west doorway. Entering the nave through this relocated door, I was surprised to find myself standing on a raised lawn floor. The elevated position incongruously cuts off several tomb recesses, which contained the remains of ancient Whithorn bishops. Curiously, if the nave had been intact, I would have had to stoop to avoid banging my head on the floor of an 18th-century gallery, whose supporting corbel stones were at eye level.

Equally intriguing as the architectural jigsaw is the story that the archaeologists have pieced together. Artifacts have revealed that Whithorn had widespread trading links: amphora from the eastern Mediterranean, tableware from North Africa, cooking pots from France and pottery from Rome. Such finds indicate that Whithorn was probably a well-established trading center before Ninian’s arrival; indeed this might have attracted Ninian to establish his base here.

Studies of graves, crypts and spoil heaps have revealed that Whithorn was the focus of shifting ecclesiastical power in Dark Ages Scotland. The power successively, and peacefully, passed from the Celts to the Northumbrians, then to the Vikings and finally to the Scots. Testimony to this includes written records of the Northumbrian Church and Celtic stone crosses. A remarkable collection of these Celtic crosses is displayed in Whithorn’s museum, which includes the Latinus Stone—Scotland’s oldest Christian monument.

Archaeologists working on grave artifacts are slowly developing a picture of 9th- and 10th-century life in Whithorn. Accumulating evidence indicates that there was a thriving community around the priory.

June Butterworth, a director of the Whithorn Trust, describes the community as a proto-town, “a community which was in transition from an agricultural to early industrial society.” Certainly Whithorn was involved in red deer farming, using antlers to produce religious artifacts; and raising cats, whose fur was sold for the trimming on cloaks and jackets. Much of the evidence for this is displayed in Whithorn’s Discovery Centre, a small museum with many hands-on exhibits designed especially for children to explore the challenge of archaeological discovery and interpretation. Like many adults, I too succumbed to playing with the instructive toys.

From the 12th to 16th centuries, Whithorn flourished as a religious center. Encouraged by the patronage of King David I, Whithorn became a major focus for Christian pilgrimage in Britain. Every Scottish monarch made at least one pilgrimage to Whithorn. James IV was a particularly lavish patron who made an annual pilgrimage, donating much land and money to the priory. Indeed, the priory’s ecclesiastical power probably originated from the wealth generated by the pilgrimage trade. So many pilgrims visited Whithorn, in fact, that the priory successfully petitioned the Scottish Parliament for an exemption on the importation of bee’s wax, used to make votive candles for sale to the pilgrims.

Pilgrimages where not all somber affairs. Certainly, those of James IV, and other noblemen, were colorful occasions. Whithorn’s market square, today’s main street, would have been filled with stalls selling divine bric-a-brac and food, and roving jesters, magicians and musicians would have entertained the weary pilgrims. The pilgrims were of many nationalities, including the hated English, who were given special passes to visit Whithorn; this early visa system limited their pilgrimage on Scottish soil to 14 days.

Many of the pilgrims would have arrived at the Isle of Whithorn, a small fishing village, a few miles south of Whithorn. Today, the Isle of Whithorn is a quaint harbor, surrounded by gaily painted fishermen’s cottages. The harbor is an anchorage for yachts and a small fishing fleet. In medieval times, its single quay would have been vibrant with the hustle and bustle of traders, sail makers and fishermen, mixing with the pilgrims’ multiple languages and accents. The pilgrims might have visited a simple 12th-century chapel at the harbor entrance, to give thanks for their safe arrival. Local custom maintains that the chapel occupies its position because it commands a view of five kingdoms: Scotland, England, Ireland, the Isle of Man and the Kingdom of God above.

The Whithorn pilgrims might have also visited St. Ninian’s Cave and Kirkmaiden Church. The cave is a secluded grotto in which Ninian reputedly lived for several years. Given that Whithorn was an established village when Ninian arrived in Galloway, this seems unlikely, though it appears to be a requirement that many of the venerated lived simple lives in some geological recess. Alternatively, perhaps it was a retreat, common among northern saints, where he could privately contemplate divine matters.

Kirkmaiden Church is nestled below the cliffs on Monreith Bay. Before descending a steep cliff path, I was distracted by an incongruously placed statue of an otter on the cliff tops—not exactly otter habitat. The statue is a memorial to Gavin Maxwell, author of A Ring of Bright Water, who was born nearby. As I admired the statue, the sunlight brightly illuminated the sea; perhaps the statue’s location was not so incongruous after all.

Kirkmaiden Church, built in the 10th century, was generally visited by pilgrims who were going on to other Scottish holy places. Having admired its fine Anglo-Norman doorway, I sat in the graveyard surrounded by stumps and fragments of 10th-century crosses. There, in the sun’s warmth, I contemplated the life of the pilgrims who had passed by here, and other religious events that occurred in this corner of Scotland.

Pilgrimages in Scotland were banned in the 16th century.

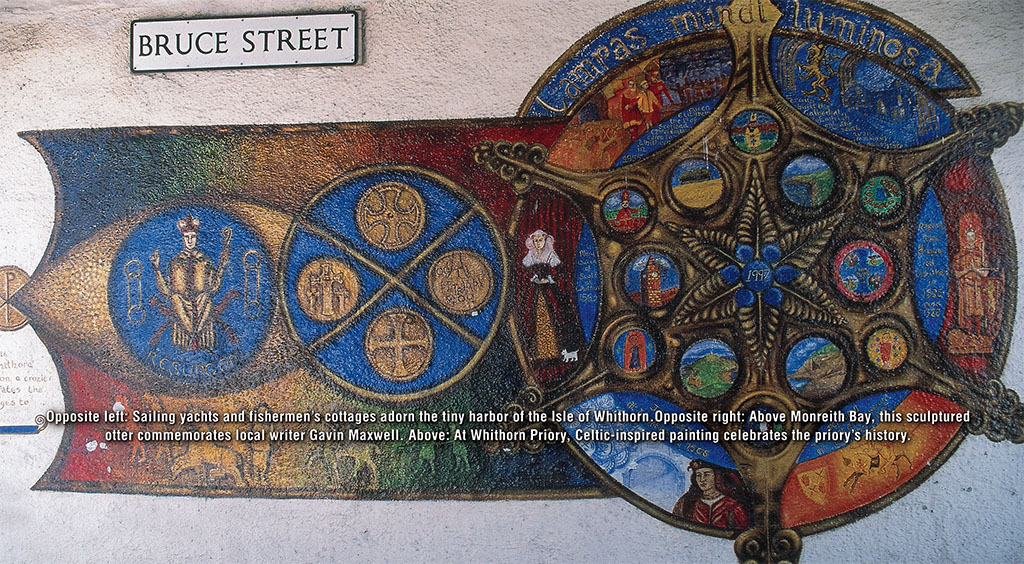

At Whithorn Priory, Celtic-inspired painting celebrates the priory’s history.

Deprived of its income, Whithorn’s influence in Scottish ecclesiastical development waned. However, this area of Galloway has long been a bed of religious rebellion and development. In the 17th century, religious issues once more came to the fore in the region’s history.

For 50 years, Galloway was a center of the Covenanter movement. Covenanters vehemently rejected the notion that the king was the head of the Presbyterian church in Scotland. They believed that Christ alone was the head of the church. Additionally, they refused to submit to the introduction of Episcopalian bishops and to use the liturgy in their services.

The whole issue came to an ugly climax on May 11, 1685, when two local women, Mary McLaughlan, 63, and Margaret Wilson, 18, were executed by drowning. Wigtown’s foreshore overlooks the bleak salt marsh and the martyr’s stake—the place of execution. For the women, their families and friends, it must have been horrific, watching the tide slowly, inexorably rising to extinguish the women’s lives.

Wigtown has become Scotland’s book capital. Browsing around the 16 second-hand bookshops was a pleasant change of pace, and several of the shops double as charming cafes too; books, good coffee and a sugary treat—perfect.

Nonetheless, religion in some guise is never far away on the Whithorn peninsula. Leaving Wigtown, with thoughts of execution by drowning still on my mind, I drove to Torhouse Stone Circle, which stands in the peninsula’s center. Even 4,000 years before Christianity, this area was inhabited by people with unknown religious convictions who constructed religious monuments. Throughout the region there are numerous standing stones and stone circles; Torhouse is my favorite.

Torhouse Stone Circle comprises 19 granite boulders set around three massive central stones. This arrangement has stood for more than 6,000 years, a silent testament to unknown pagans and their gods. With the day’s final light gilding the granite boulders, it was awe-inspiring to consider the intensity of the religious passion that has been expressed in this part of Scotland: of ancient peoples hauling heavy stones to hilltops; of a man called Ninian, whose convictions took him amongst the quarrelsome Picts; of innumerable pilgrims, who made arduous journeys to reach Whithorn; of two women who stoically drowned for their beliefs. It is quite humbling.

* Originally published in 2006, updated in 2023.

Comments