Across the High Seas in Search of Adventure.

Britain’s island nation has always looked across the high seas of history for adventure. Meet up with her most famous explorers when you drop anchor at some great attractions.

The world’s largest maritime museum, set in the lovely Greenwich World Heritage Site, is the perfect place to find your sea legs. Head straight for the Explorers gallery that reviews searches for new land and knowledge, trade and booty across the eras. Meet the dashing figures of Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh from Elizabeth I’s golden age of adventure, and lesser-known heroes like Sir John Franklin (1786–1847): the veteran of Trafalgar who surveyed the Arctic, mapping over 3,000 miles of north Canadian coastline before he and his crew perished on a final Arctic expedition.

Without these adventurers, we wouldn’t have our modern ships and navigational equipment, knowledge of the world and its inhabitants. Plunge deeper into the theme in the Oceans of Discovery and Atlantic Worlds galleries.

John Cabot

It’s impossible to shrink what you know of the world and imagine setting sail like John Cabot did into uncharted waters with little more than almanacs, astrolabes and nocturnals to navigate. Clamber aboard the replica of his ship Matthew moored in Bristol’s Harborside, and you’ll at least get a flavor of crew life. Seventy-eight feet long, the jauntily painted, square-rigged caravel is a compact wooden vessel just like its Bristol-built original. It looks majestic with mainsail and foresails set for a trip offshore. Or join a harbor cruise (and try to ignore the modern engine).

In 1497 Italian-born Cabot sailed from Bristol with merchant backing and 18 crew in search of a westerly route to Asia (quicker than heading east), hoping to lay hands on gold, spices and other luxuries. Success would enhance England’s position as a major trading center. He actually stumbled across Newfoundland—he wasn’t to know it would be in the way; Europeans didn’t yet grasp the existence of mainland America. Cabot’s adventure made him famous, and Henry VII granted him an annual pension. He sailed again the following year and vanished, his fate unknown.

Cabot wasn’t the first European to sail to the New World, but he certainly spurred others to voyage across the Atlantic. He also contributed to the historic development of Bristol as a thriving transatlantic port—renowned for the import of Newfoundland cod.

Sir Francis Drake (c. 1540–96)

As the Spanish Armada approached England’s shores on the afternoon of July 19, 1588, Francis Drake coolly finished his game of bowls on Plymouth Hoe. That’s the tale, anyway. Mention Drake’s name, and adjectives like swashbuckling and buccaneering come tumbling: he epitomized the spirit of an age when state-sponsored piracy went hand in hand with exploration and warfare.

Peel away the legends, and what do we have? Buckland Abbey in Devon holds some of the answers. Drake lived in the monastery-turned-stately home for 15 years from 1582, and Journeys, a modern interactive gallery here, sets us on the trail of his career.

A straight-talking Devon lad of yeoman stock, Drake took to the seas at an early age. His belly was fired by his Protestant faith, intense patriotism and hatred of the Spanish, who once ambushed him when he was on an African slave-collecting mission.

In 1577 he crossed the Atlantic on Pelican, renamed en route Golden Hinde, raiding Spanish ports along the South American coast. When you’re in London, look up the replica Golden Hinde at St. Mary Overie Dock. www.goldenhinde.co.uk. The first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe, Drake found Cape Horn, disproved the existence of a continent stretching southward from Tierra del Fuego and claimed Nova Albion (California) for Queen Elizabeth I.

He returned in 1580, a hero enriched with plunder that the Queen shared. A knighthood followed, and Drake spent £3,400 acquiring Buckland Abbey.

The adventurer went on to “singe the King of Spain’s beard” by destroying many of the king’s vessels in Cadiz harbor in 1587, and he played a crucial part in seeing-off the Armada in 1588. After that, it was down hill: he was court martialed for a campaign gone wrong, and in 1596 he died of dysentery in the West Indies. In Buckland Abbey’s Treasures gallery is the drum he used on his last voyage. It’s said it’ll beat of its own accord to summon the Elizabethan sea dog back from the dead should England be in danger.

Francis Drake

Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1552–1618)

Visit: Sherborne Castle, Sherborne, Dorset

www.sherbornecastle.com

Walter Raleigh once threw down his cloak to prevent Queen Elizabeth I muddying her royal toes in a puddle—and if the vignette isn’t true, it should be. The comely courtier was fond of the flamboyant gesture. Even on the scaffold in 1618, he played to the crowds, testing the ax with his finger and declaring, “This is a sharp medicine.” He eschewed a blindfold: demonstrating courage as well as charisma.

Court favorite, politician, explorer, businessman, historian, poet and peacock, Devonshire-born Raleigh was a man of many parts. In the 1580s he organized expeditions to North America in search of trade and gold, and named Virginia in honor of the Virgin Queen. Colonization of Roanoke Island ultimately failed, but gave later travellers an inkling of what to expect. Raleigh also is said to have introduced tobacco and potatoes to England.

After a spell in the Tower of London—he had incurred the Queen’s wrath by secretly marrying royal maid Bess Throckmorton—he sailed in 1595 to South America to look for the fabled E1 Dorado and its gold without success.

Later accused of treason against King James I, he spent another decade-plus in the Tower, where he wrote his History of the World. Released to look again for E1 Dorado, to enrich royal coffers, Raleigh faced the executioner’s block after his men harmed Spanish settlements in contravention of the King’s wishes.

Follow in Raleigh’s steps to Sherborne in Dorset, his “Fortune’s Fold.” He acquired what’s now called the Old Castle in 1592, but finding it too damp he built a new mansion, today’s Sherborne Castle. Although much altered, it still bears his coat of arms and device of the buck in the plaster ceilings, and the kitchens and bakehouse date from his time.

The pipe Raleigh reputedly puffed on the scaffold is here, too—and the stone seat where a servant doused him with ale, fearing his smoke-wreathed master was on fire.

Wander Sherborne’s quaint old town streets to the museum, where you’ll find plans and drawings relating to Raleigh’s castle, and the abbey where Sir Walter and Bess worshipped. www.sherbornetown.com.

Bartholomew Gosnold (c. 1572–1607)

Gather around the impressive English oak fireplace in the Great Hall at 16th-century Otley Hall and imagine the animated conversations as Bartholomew Gosnold and his colleagues planned their voyages to the New World. This former Gosnold family seat, with its magnificent wooden panelling and carved beams, is just the place to pick up history’s echoes.

Gosnold, a Suffolk councilman, lawyer, explorer and privateer, embarked on two great expeditions. In 1602 he crossed the Atlantic in Concord, chartered by Raleigh among others, with the intention of establishing a colony in Northern Virginia (New England). In the process he pioneered a direct route due west from the Azores, arriving at Cape Elizabeth in Maine. He then followed the coast to anchor in York Harbor, before progressing to and naming Cape Cod, as well as Martha’s Vineyard—so-called for his daughter who had died in infancy. He built a fort on Elizabeth’s Island: now Cuttyhunk and part of the town of Gosnold.

Lack of provisions sent the would-be settlers home, but accounts of their travels stirred great interest. Gosnold became a prime mover in the 1606–07 voyage that led to the establishment of Jamestown, the first permanent English-speaking settlement in the New World. Sadly, he died from dysentery that deadly first summer in Jamestown and is something of an unsung hero of this chapter in Anglo-American heritage.

Captain James Cook (1728–79)

Captain James Cook really made headway in the Pacific, with three momentous voyages that would see him chart that ocean, opening up New Zealand and Australia to later settlement. Over more than eight years, he recorded previously unknown islands, radically changed perceptions of world geography and set a new standard for maps.

As befits the man, there’s an accurately plotted, 70-mile circular tour visitors can follow around Captain Cook Country if you wish to trace his early life: from the birthplace museum in Marton, North Yorkshire, to the Captain Cook Memorial Museum, Whitby. www.captaincook.org.uk/tour. The latter is in the harborside house where young James lodged as a collier’s apprentice with shipmaster John Walker and trained as a seaman. It’s packed with artifacts and information, including Cook’s pioneering voyages and their scientific studies of flora and fauna.

James Cook joined the Royal Navy when he was 27 and later surveyed the St. Lawrence River and Newfoundland, in preparation for the capture of Quebec. His Pacific voyages began in 1768, aboard Endeavour, when he took scientists to Tahiti to observe the transit of Venus. He then continued on to look for the continent rumored to lie in the southern ocean, circumnavigating New Zealand and surveying the east coast of Australia.

On his second expedition, when he also tested a copy of John Harrison’s new marine chronometer, Cook sailed the icy fringes of the Antarctic, noted more Pacific islands and travelled farther south than anyone before him, laying to rest the myth of the great southern continent.

Renowned for maintaining the wellbeing of his crews, Cook kept scurvy at bay with a ship’s diet rich in pickled cabbage. He cared also for the natives he met, making it tragic irony that, on his final voyage in search of the Northwest Passage linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, he was killed by islanders on Hawaii during an unfortunate confrontation.

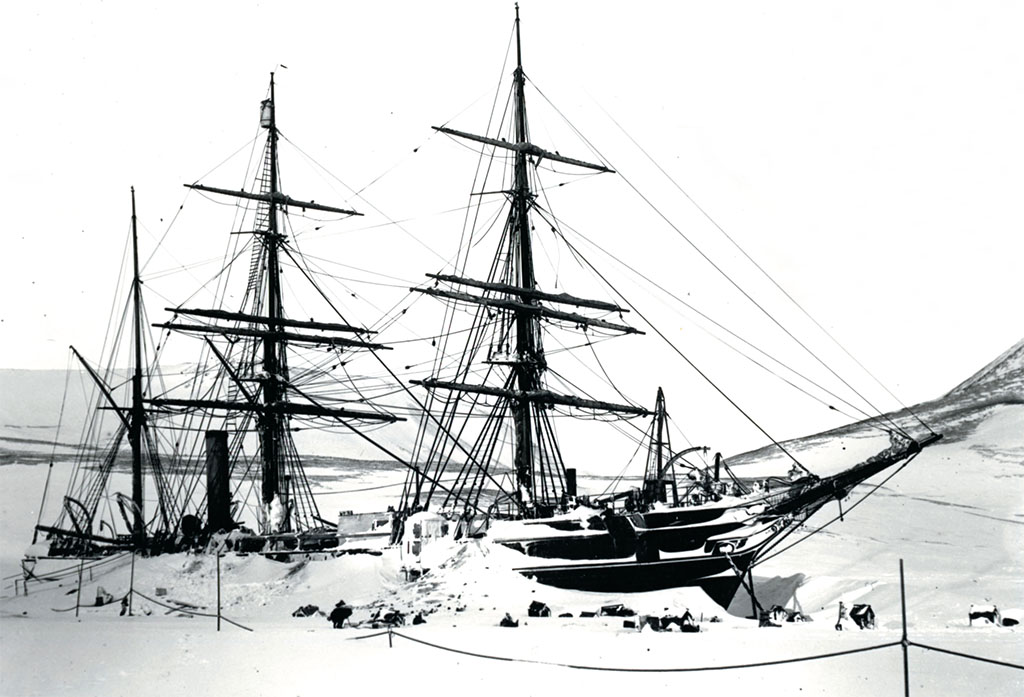

COURTESY OF DUNDEE HERITAGE TRUST

Dr. David Livingstone (1813–73)

“Dr. Livingstone, I presume?” Henry Morton Stanley, sent by the New York Herald, made the famously courteous enquiry on happening across a red-jacketed gent at Ujiji on the shore of Lake Tanganyika on November 10, 1871. David Livingstone had set off to Africa in 1866 and been unheard of since.

In fact, the trip was the intrepid explorer-missionary’s third venture into “darkest Africa,” as it was then widely known: travels that filled in more gaps on the continent’s map than anyone had previously done. Livingstone furthered scientific discovery and paved the way for British colonization in east Africa.

The venerable Scotsman was born in a humble Blantyre tenement in 1813, where today you’ll find the atmospheric David Livingstone Centre that puts his childhood in context and highlights his travels in Africa. In his 20s he decided to become a missionary and qualified as a doctor in 1840. There’s a fascinating range of Livingstone’s possessions on display, from medical and navigational equipment to letters and, not least, his iconic red shirt.

During his expeditions “to make an open path for commerce and Christianity,” the Victoria Falls on the Zambezi River were discovered, as well as Lake Nyasa (now Lake Malawi). The horrors of the Portuguese slave trade were also exposed, and Livingstone campaigned against the practice on his third trip when he went in search of the source of the Nile. He spiked such feelings against the trade as to deal it a fatal blow.

Having endured much danger and suffering, Livingstone died in 1873 not far from another of his discoveries, Lake Bagweulu. His careful recording of his geographical and scientific findings wrote him into the history books; the fact that even the slave traders he opposed called him “the very great doctor” speaks for itself.

Comments