Samuel Pepys.

On Feb 23, 1633, Samuel Pepys was born in London. Pepys bore witness to some of London's most notable events, but who exactly was the famous diarist?

To read the diary of Samuel Pepys is to be transported back into his world of 17th-century London. With enthusiasm, wit, and a keen eye for detail, Pepys brings to life the atmosphere, people, events, and places of his time. Through his diary, begun in 1660 as Pepys launched his public career, we have an “I was there” account of Restoration London—from the politics of the period to the daily fare at the table to remarks about the king’s mistresses. Through his eyes, we witness the grandeur and ceremony of Charles II’s coronation in 1661 and several years later feel terror as the plague spreads across the city.

In 1666, with the Great Fire raging for four days and nights, Pepys so carefully records the turmoil that one can almost smell the smoke from “the churches, houses, and all on fire and flaming at once…the streets full of nothing but people and horses and carts loaden with goods, ready to run over one another….”

Born of humble parents in Salisbury Court, off Fleet Street on February 23, 1633, Samuel Pepys was a quick and clever student. Awarded scholarships, he was sent to St Paul’s School and thence to Magdalene College, Cambridge, taking his degree there in 1654. Through the influence of a distant relative, young Pepys acquired a clerkship in the Exchequer, eventually working his way into advanced positions of responsibility. A diligent and successful civil servant, Pepys was equal to whatever challenges came his way and was, for much of his life, the most important administrator of the British navy.

Read more

Pepys was, by birth, career and personal inclination, the quintessential Londoner. He delighted in the city and everything it offered. With interests that ranged from music, theater, and fashion to politics and science, he knew London intimately. Whether on navy business at Whitehall or visiting the newest alehouse, Pepys made his daily rounds—walking the streets, popping in and out of buildings, and traveling the Thames by ferry.

Although time has overtaken and destroyed many of Pepys’ haunts or enclosed them with modern life, it is a fascinating pilgrimage to go in search of the great diarist. With his genius for happiness and pleasure in life, Pepys is an exciting and interesting companion, an irresistible guide to his world. Today, more than 300 years since he strode through London as an energetic young man, there is a special feeling of communion with him when surrounded by the places and things he knew.

13 April 1661: To Whitehall to the Banquet House and there saw the King heale, the first time that I ever saw him do it—which he did with great gravity, and it seemed to me to be an ugly office and a simple one.

This ceremony that Pepys observed with some disdain was the ancient custom known as “Touching for the King’s Evil”—a laying on of royal hands to cure the poor souls afflicted with scrofula, a form of tuberculosis. While Pepys may not have been impressed with the ritual, it became so popular during the reign of Charles II that special certificates of the application had to be issued to satisfy the many requests.

Image: Getty

The Banqueting House itself, built in 1622 with lavish gilt and grandeur, must have pleased the normally ebullient Pepys whose diary entries often overflowed with superlatives such as “the beautifullest” and “the noblest.” As part of the palace of Whitehall - the sovereign’s main London residence from the time of Henry VIII - the Banqueting House was designed by Inigo Jones as a sumptuous setting for royal banquets, masques, and entertainments.

In 1625 Charles I commissioned the Flemish painter Peter Paul Rubens to paint the carved and compartmented ceiling for the vast sum of £3,000. The nine magnificent paintings, completed in Antwerp over a period of several years and shipped to London, were put in place in 1636. Tragically, those paintings commissioned by the king when he ascended the throne were among the last things he would look upon. Passing beneath them in January 1649, Charles I stepped through a window at the Banqueting House onto a specially erected, black-draped scaffold to his execution. Although Pepys had not yet begun his diary at that time, he was there at that moment of history to witness the beheading of the king.

The Palace of Whitehall was destroyed by fire in 1698, leaving only Inigo Jones’ early masterpiece, the Banqueting House, surviving to stand today as a testament to the glory of a regal past.

26 May 1667: [To church at St. Margaret’s and did] entertain myself with my perspective glass up and down the church, by which I had the pleasure of seeing and gazing at a great many fine women: and what with that and sleeping, I passed away the time till sermon was done….

Pepys always had a lusty appreciation for women, many women, and even a solemn worship service could not deter him from casting an admiring eye at some pretty maidens, as he did on this particular spring day.

Twelve years earlier in this same church, Samuel Pepys looked upon one particular maiden - an attractive “portionless” girl named Elizabeth - as they were married in 1655. Only 15 at the time, Elizabeth emerges from Pepys’ diary over the following years as a lively, spirited wife who often gave as good as she got. The Marriage Register at St. Margaret’s Westminster records December 1, 1655, as the day of their marriage, but Pepys and his wife always kept October 10 as their anniversary.

Although St. Margaret’s was not the church Pepys attended regularly, he had many occasions to visit this church so near the center of government. Consecrated in 1523, the present church is graced by a remarkable stained glass window filtering light over the altar. Commemorating the marriage of King Henry VIII and his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, this window is especially notable for containing some of the finest pre-Reformation Flemish glass in London. Opposite this window, over the west door, is another significant window commemorating both the fact that Sir Walter Raleigh was executed just a few yards from the church and that he was subsequently buried underneath the altar. Known since 1614 as “the Parish Church of the House of Commons,” St. Margaret’s Westminster has a rich history that includes not only Samuel Pepys and Raleigh but also a strong tradition of many parliamentary religious observances that continue to the present time.

24 May 1663: To church and over against our gallery I espied Pemberton and saw him leer upon my wife all the sermon….

Poor Pepys! Such distractions of jealousy and in his own parish church of St. Olave’s! From the time Samuel Pepys was appointed Clerk of the Acts in 1660 and moved his household from Axe Yard to Seething Lane, he regularly attended St. Olave’s Church. Standing at the corner of Hart Street and Seething Lane, just a stone’s throw from the Tower of London, the present church, built about 1450, is one of the few churches that escaped the Great Fire of 1666. While the area around the church is dominated now by large, modern office buildings, nearby streets with names such as Mincing Lane, Fenchurch, Jewry Lane and Crutched Friars still evoke a bit of the world that Pepys knew.

Medieval church of St Olave on Hart Street in The City surrounded by modern structures in London England

It is when you enter the gateway of the churchyard, though, that you can almost imagine the short, dark, keen-eyed, periwigged Pepys at your elbow, recounting the latest piece of news. Pepys refers several times to this churchyard, which he found quite frightening to pass through after 1665 because of the many interments of plague victims. But pass through he did to reach the outside staircase—no longer there—leading to his seat in the navy pew. From his place in the south gallery, Pepys could, following Elizabeth’s death in 1669, look directly across at the charming bust of his wife, placed high up on the wall near the altar. Elizabeth died childless at the age of 29 and was buried in a vault in the little church.

Pepys died on May 26, 1703, and on June 5 - after nearly 40 years as a parishioner at St. Olave’s - was buried at 9 o’clock at night, “in a vault by ye Communion-table.” Each year, a special service commemorating Samuel Pepys is held on or near May 26 at St. Olave’s Church. During the service—attended by the Master and Wardens of the Clothworkers Company (Pepys was a master clothworker in 1677) and others who honor the diarist - the Lord Mayor places a wreath of laurel leaves in front of the communion rails and an address is given, usually by a recognized Pepys authority. It is a tribute Pepys would have enjoyed.

5 September 1666: About 2 in the morning my wife calls me up and tells of new cryes of ‘Fyre!’—it being come to Barkeing Church which is the bottom of our lane. I up to the top of Barkeing steeple, and there saw the saddest sight of desolation that I ever saw. Everywhere great fires. Oyle cellars and brimstone and other things burning. I became afeared to stay there long; and therefore down again as fast as I could….

At the opposite end of Seething Lane, just a short stroll from St. Olave’s and past the site of Pepys’ house—now marked by a small, enclosed garden and bust of Pepys—is the church with the delightful name of All Hallows, Barking by the Tower. Rebuilt in the Middle Ages over a Saxon church dated from around 675, there is, preserved in the crypt, a Saxon arch said to be the oldest arch in London as well as pieces of two Saxon crosses and a Roman pavement.

Given its position atop a rise, it is easy to understand why Pepys dashed to All Hallows in the middle of the night to survey the spread of the fire as it moved ever closer to his own home. Certainly, with the perspective gained from the steeple, he could look over the entire area and judge “the whole city almost on fire.”

Although the church survived the raging flames of 1666, it was not so fortunate during World War II. Suffering extensive bomb damage, All Hallows was restored in 1950 and stands today next to the rushing traffic of Byward Street—a small church made famous by a diary entry written more than three centuries ago.

Despite his history with women, Pepys never remarried but went on with his official career until 1688, regarded for as long as he lived as a great authority on naval matters. For 10 years following Elizabeth’s death, Pepys continued to live in Seething Lane, close by his work at the Naval Office. In 1679 he moved his household to 12 Buckingham St., Westminster—a narrow, dead-end street overlooking the embankment by the Thames. Begun less than a decade after the Great Fire, the street’s tall 17th-and 18th-century houses were built with an eye toward fire prevention, using brick and minimal timber.

The cream-colored house at No. 12—not open to the public but identified with a plaque noting its association with Pepys—has changed little since the days when he climbed the steps opposite the water gate as he made his way home at the end of the day.

Nine years later, in 1688, Pepys once more moved, just down the street to a somewhat grander house at No. 14. The original house has not survived the years, but a plaque marks the site as Pepys’ residence until 1701. It was here on Buckingham Street that Pepys lived for most of his retirement from public service, beginning in 1689. A passionate bookman, Pepys now had the leisure to read, search for just the right volume for his library, make music and meet and exchange letters with friends such as John Evelyn, Isaac Newton, Christopher Wren, and William Penn.

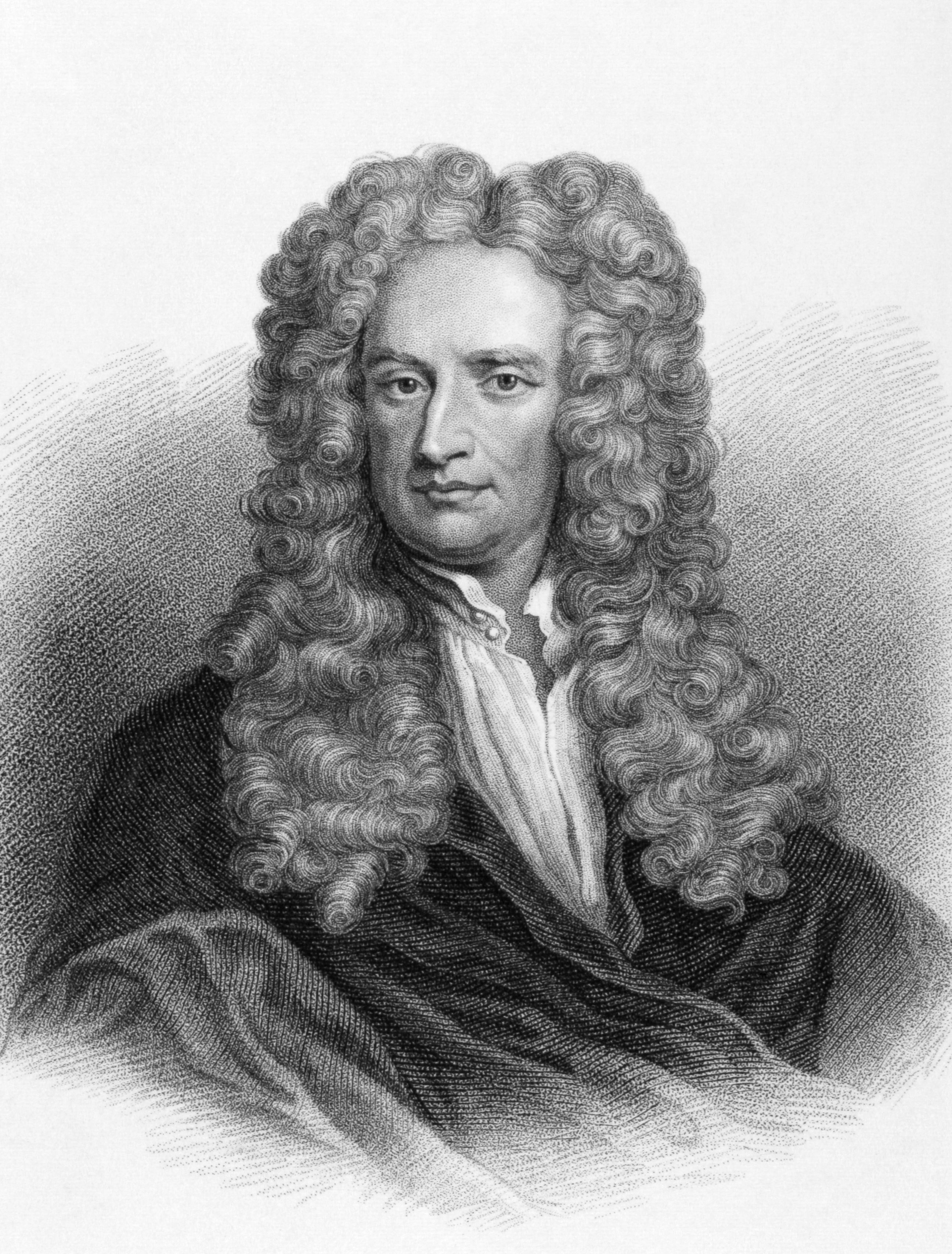

Image: Isaac Newton

Elsewhere in the city, in an area where Pepys would have felt right at home, a small museum dedicated to his memory was opened in 1975 in one of the few timber-framed buildings to have survived the Great Fire. Overlooking busy Fleet Street with its constant flow of traffic, the large room—known as Prince Henry’s Room—is a peaceful reflection of another time. With richly carved wooden paneling, windows flourished with stained glass and an ornate 17th-century ceiling said to be the finest example of Jacobean plasterwork in London, it is an appropriate setting for this interesting collection of Pepys memorabilia. Along with prints, maps and documents pertinent to Pepys and some furniture said to have been his, there is a framed letter written by him in 1669 and a page from a 17th-century satire attacking Pepys and his clerk Will Hewer for the bribes they took at the Navy Office. Although this site at 17 Fleet St. is arbitrary since Pepys is not known to have had any connection with the building, it is nonetheless a charming museum that fittingly celebrates the life of the great diarist.

There can be finally, no better end to one’s tour of Pepys’ world than a visit to the Pepys Library at Magdalene College, Cambridge. His library survives there—intact and complete—just as he directed in his will. Beautifully bound in calf and tooled in gold, the 3,000 volumes are arranged in the exact order Pepys specified in the oak bookcases that he had made over the years by dockyard joiners. Here too is Pepys’ own library table where he wrote and pored over the books that meant so much to him. Of special interest, of course, is the original manuscript of his great diary—neatly handwritten in ink in shorthand, with occasional personal or place names in longhand. It is a remarkable accomplishment.

It has been said that Samuel Pepys would be remembered today even if he had not written his immortal diary. As the great administrator of the navy, president of the Royal Society and friend to many of the great intellects of his time, his place in history is secure. But to stand in the Pepys Library, surrounded by his books, the presses and the diary he so meticulously labored over, is to feel the essence of Samuel Pepys. It is that which remains his most eloquent and enduring memorial.

* Originally published in July 2016.

Comments