St. John the Bapist, at Cirencester.

Join Dana Huntley as he traverses through Devon and Essex

Social policy was admittedly not on my mind as I landed at Heathrow and headed west on the M4 looking for what adventures might befall. Old friends and long-time British Heritage readers, Tad and Norm Berkowitz, joined me on the road. Our first destination was the aged seaside resort town of Weston-super-Mare. That evening, Siân Ellis and her mate Dave and my good friends from the Valleys, Carol and Norman Jarrett, all crossed the Severn from Wales to join us for a delightful evening of badinage, good beer and a setting to rights of the Atlantic alliance. I could be very au courant for a journalist and call it a “focus group.”

Read more

The seafront at Weston-super-Mare was torn asunder with construction works and preparations for the much-heralded reopening of Weston’s pier the next weekend, following its virtual destruction by fire a few years ago. Norman and Carol opined that Weston was indeed a much revived and improved place since their last visit a couple of decades ago. That’s always nice to hear.

The weather picked up an autumnal chill the next day as we headed down the Bristol Channel and turned to the west on the A39 at Bridgenorth toward Exmoor and the North Devon coast. Those tall Devon hedgerows gave way soon enough for the dramatic coastline. We pottered about a little at medieval Dunster to see its early 17th-century yarn market, and at Minehead to circle its late 20th-century Butlins holiday camp.

As anyone who has ever been down on that coast will recall, its most memorable feature is probably Porlock Hill. After all, it’s not every day you drive up a two-mile corkscrew at a 25 percent gradient. It’s not every day, either, that you find such dramatic views when you reach the top—across the channel to South Wales to the north and over the stark heath of Exmoor to the south.

The stunning little harbour town of Lynmouth made a great base for a couple of days exploring Lorna Doone Country. We hugged the coast on single-track roads through Valley of the Rocks and made it as far south as the famous picture-postcard village of Clovelly. The health and safety mavens must have nightmares just thinking of Clovelly’s steep, cobbled, traffic-free street leading down to the tiny harbor—where residents transport their groceries to the cottage door on wooden sleds.

Harbour town of Lynmouth.

Having had quite sufficient of the motorways, I charted next a cross-country dogleg toward Gloucestershire. That found us having morning coffee in Glastonbury and lunch in Trowbridge with a final destination of Cirencester. Long one of my favorite market towns, Cirencester makes a great base for dawdling around in the Cotswolds—especially during the off-season. Then again, there is nowhere in the Cotswolds that is free from the crowds during the popular summer. A good bit of Keats’ “mellow fruitfulness” hung in the bright October skies as we traveled the pretty lanes of The Slaughters and deep into the countryside to Ched-worth Roman Villa.

Cheltenham, on the other hand, has always been a traffic boondoggle and, eh, navigational challenge. It was doubly so since the Cheltenham Literary Festival and a race meeting were both in full swing when I met British Heritage writer Becky Gardner in town for lunch and some story-building plans.

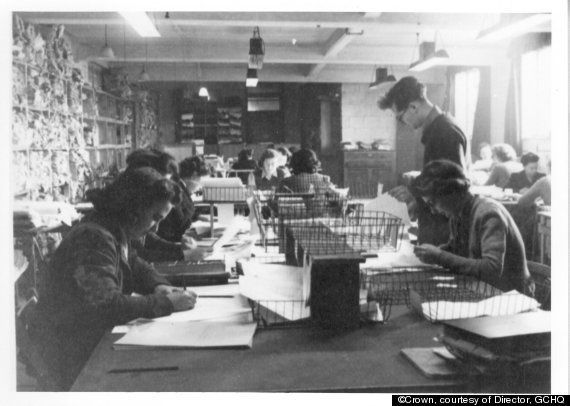

From the pastoral landscapes of the Cotswolds, it’s a fair drive and a world away to the Essex coast and the old Cockney seaside playground of Southend-on-Sea. We broke the journey with a visit to Bletchley Park. You can read all about the secretive World War II code-breaking center in Jean Paschke’s story coming in the next issue. I got the excellent tour, however—and the pictures. And what a fascinating tale it is.

Code breakers at Bletchley Park.

It’s a bit of wishful thinking, really, to call the town Southend-on-Sea. More like Southend-on-the-Thames-Estuary, since the lights of Canvey Island and its power station are always visible upriver, and the views across the water are of Sheerness and Kent’s Isle of Sheppey.

I’d never explored the flat fens of the Essex coast. We zigzagged through Southend’s undistinguished suburbs into the country, meandering with seeming aimlessness north through the fertile farmland as far as Burnham-on-Crouch. Along one low ridge overlooking the alluvial plain toward the sea a huge derelict cement bunker stood perched upon reinforced concrete plinths on the high ground. I learned later that it was a World War II observation post, where coast watchers scanned the skies toward Nazi-occupied Europe to provide early warning of bomber squadrons heading for London or the airfields of East Anglia.

Back in London, the political atmosphere was powering up in anticipation of the Government’s promised “spending review.” While I wanted a day in town, I also wanted a run around the Chilterns. So, we encamped in the suburbs just outside the M25, easily accessible to both. On the way, we paused at Hatfield House, where the parkland and shops were open even if the Tudor mansion where Elizabeth I learned she was queen was closed for the season.

The courtyard was full of the lorries, trailers and accouterments of film-making. It seems they were making a movie about Marilyn Monroe, unlikely as that sounds in the context.

The headline read “Ax Wednesday” in Second-Coming type as the papers reported on Chancellor George Osborne’s announcements of the Government’s austere fiscal measures to address Britain’s deficit-ridden public purse. The loss of some 490,000 public sector jobs seems staggering, but then one out five British workers serves on the public payroll. The Government plans also seek to curtail Britain’s generous “benefits” program to provide greater incentive for folks to actually seek jobs.

Remarkably enough, on the day this was going on across the street in the Commons, MP Patrick Mercer of Newark actually took more than an hour of his time to visit with me in his office at Portcullis House. As a military historian and former army officer, Mercer was understandably shaking his head at defense cuts that will leave Britain with an aircraft carrier expected to lack for eight years any fighter jets to fly from its deck. We had a most genial visit swapping tales of history and politics until the division bell rang summoning him back to the floor for a vote.

I had another first the next day, driving down through northwestern London—Harrow, Wembley and Ealing—instead of around it, to Kew Gardens. Yes, it took a little longer. It had been many years since I visited the Royal Botanical Garden, but Kew certainly has not lost its charm. Somehow, though, its hundreds of acres seem larger than they used to. The highlight for me was the Treetop Walk, roughly 10 stories into the air through a canopy of hardwoods. The views were fabulous over the garden and London’s sprawling cityscape. ’Tis not an exercise to be recommended for those souls timid of heights, however; the walkway flooring is simply of steel mesh. Some folks just couldn’t pry their hands from the railing.

The tea is always reliable, and the coffee is generally better than it used to be. There’s something unreasonably comforting about the “full English breakfast,” even if one of its standard components is tinned beans they insist upon calling “baked.” It is a rare privilege to leave my oatmeal behind and indulge in those breakfasts on behalf of British Heritage—and I am ever conscious and ever delighted that you choose to come along.

* Originally published in 2018.

Comments