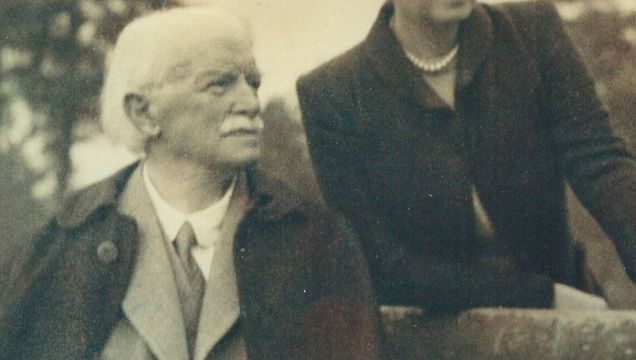

Former prime minister and 20th-century statesman David Lloyd George reflects here with Frances Stevenson, his longtime secretary, and mistress. It is 1943, the year they were marriedRuth Longford.

A political mistress and her legacy of love.

My grandmother sometimes spoke to me about the past, knowing that I planned to study history at university. Her mother had brought her up to expect that after a short period of respectable employment she would marry. At 23, Frances felt trapped as a language teacher in a girls school, and so she began training herself in typing and shorthand, hoping to become a journalist. Instead, she became a secretary to David Lloyd George.

Frances spent the summer of 1911 with the Lloyd George family, coaching the youngest daughter. She liked them all but was particularly dazzled by Lloyd George, at his peak politically as a reforming Chancellor of the Exchequer. At the end of the summer, Lloyd George continued to invite her to do small translation jobs for him. Finally, he asked her to become his secretary but explained that he could work with her only if he made her his mistress as well. A difficult choice, she went away to consider it.

Lloyd George then wrote that an insider-trading scandal over Marconi shares was about to break, and he needed her during that crisis. Feeling needed to be a persuading factor for Frances, and from then until the end of her life she was Lloyd George’s most ardent and loyal supporter.

From the seclusion of a small girl's school, Frances moved to the heart of world events. Over the weekend when the British Cabinet debated whether to enter the First World War, Frances stayed with Lloyd George because his wife, Margaret, preferred to spend a great deal of time at the family home in Wales. Frances, unlike Margaret, loved to pamper people and create a beautiful and comfortable home. And for many years, she had no children to distract her. Lloyd George’s daughter Megan became a bitter enemy when she discovered that her former tutor was having an affair with her father, but even she admitted that being with Frances was “like sinking your feet into a thick pile carpet into which you sank your feet gratefully.”

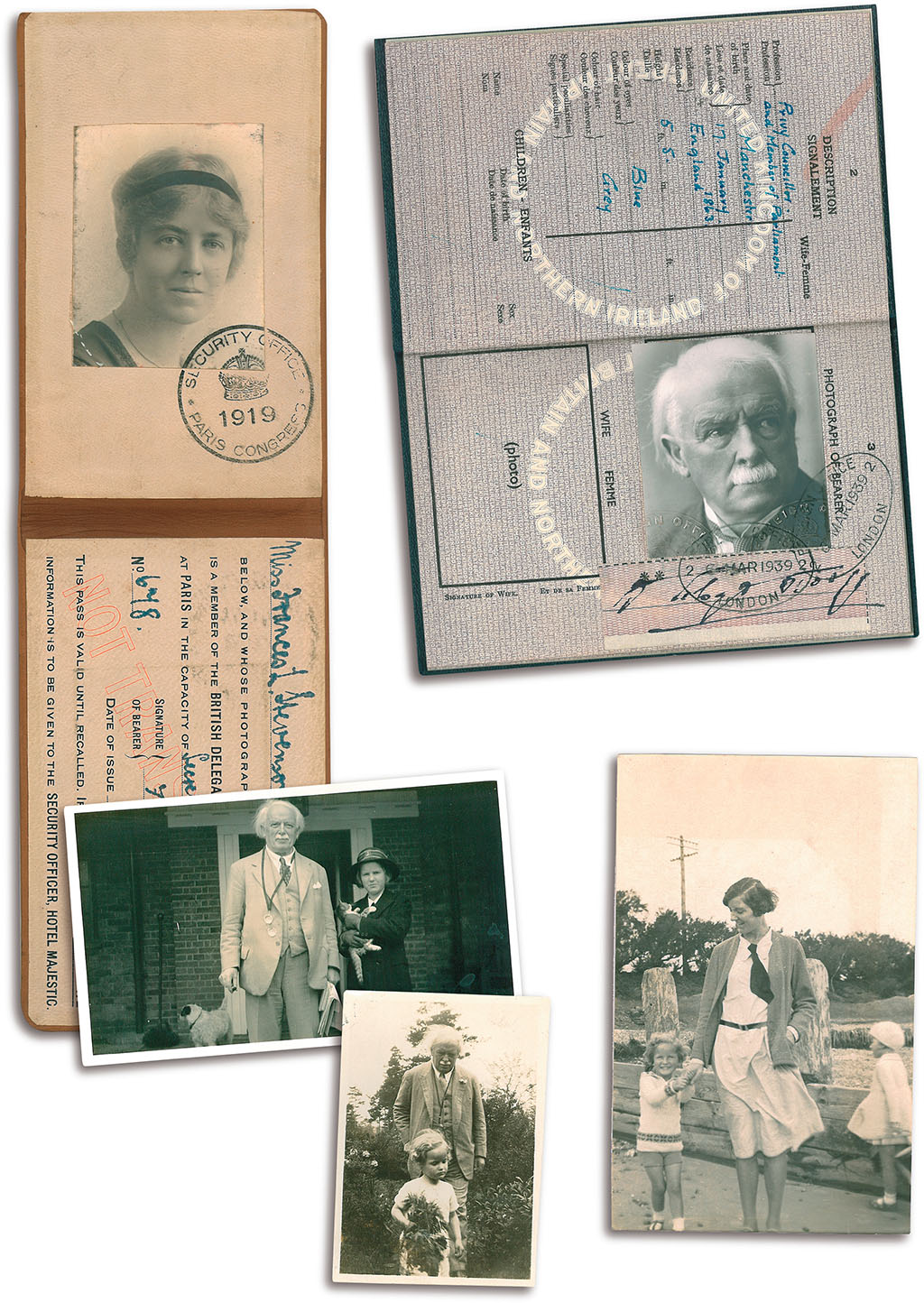

Frances Stevenson’s credentials to accompany Lloyd George to the Versailles Congress of 1919. Lloyd George’s visa for his prewar visit with Adolf Hitler. The author’s mother, Jennifer Stevenson, and her nanny enjoy a carefree day. Jennifer toddles along beside Lloyd George. At age 12, Jennifer poses with Lloyd George before returning to school.

Frances’ ability to speak fluent French made her invaluable during the long months spent in Paris discussing the peace terms at Versailles. When I studied the First World War, she told me anecdotes. Apparently, President Woodrow Wilson irritated Parisians because he turned his rented house into a little bit of America; French governesses had to cross the road with their prams when they reached the pavement outside his house so that he would not be bothered by the noise.

One poignant story I remember was about Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the Polish prime minister, and former concert pianist. He was asked to play the piano for relaxation one evening after a long day of discussion, and he said that he could not. According to him, if he did not play for one day, he noticed the difference; two days and his critics noticed; and if he did not play for three, his public noticed. Since he had not played since the start of the war, his refusal to perform prompted Frances to sit down at the piano instead, and she entertained the guests—far less skillfully, but well enough for everyone to sing along.

Lloyd George was faithful to neither his wife nor his mistress, but Frances nonetheless kept her position with him, always putting his interests first—even above those of the child she eventually chose to bear him at the age of 40. Frances and Lloyd George’s daughter, Jennifer Mary, was born on October 4, 1929.

Jennifer felt loved by both Lloyd George and Frances but, although they did visit her, she lived separately from them and was brought up mainly by nannies. Though relations between mother and daughter were never easy, I, Jennifer’s daughter, loved my indulgent grandmother uncritically.

COURTESY OF RUTH LONGFORD

At university, I was able to use my inside information to write a dissertation about Lloyd George and his controversial attitude toward World War II. Winston Churchill, to Lloyd George’s intense chagrin, once suggested that Lloyd George might emulate Vichy France’s Premier Henri Philippe Pétain and collaborate.

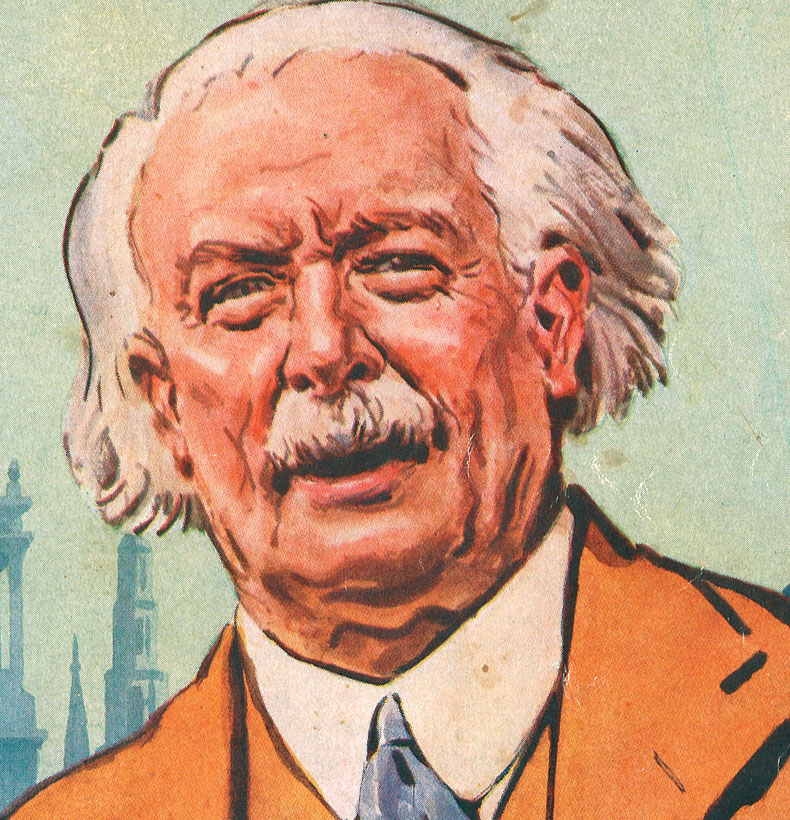

Indeed, Lloyd George was publicly pessimistic about the outcome of this war, and only too aware of how close to defeat the British had been in the First World War. He was horrified by the alliance Adolf Hitler managed to broker with Josef Stalin in 1939 and saw Britain standing alone and ill-prepared. Hitler’s mistakes, and Japan’s causing the United States to enter the war, were lucky for Britain. After meeting Hitler in 1936, Lloyd George had not expected him to make mistakes.

During the depression of the 1930s, Lloyd George yearned to do what Franklin D. Roosevelt was doing in America, or indeed what Hitler was doing in Germany—invest in schemes that would put people back to work. He traveled around Britain campaigning for votes to support his own “New Deal,” and just as he had copied the German insurance schemes for his reforming innovations in 1906, he went to study what Hitler was doing to restore Germany’s economy in 1936.

No one outside Germany in the ’30s fully understood the lengths to which Hitler would go. Lloyd George had no idea of how far Hitler’s tyranny and control were already beginning to reach, but he did condemn Hitler’s anti-Jewish stance. He thought it was wrong and wrote forcefully to that effect in a magazine called The Standard in April 1937.

Lloyd George was 76 when World War II began. He was not fit enough to work as he had in World War I, but he did make a significant contribution. When Neville Chamberlain appealed for loyalty from the House of Commons, Lloyd George stood up and said: “He has appealed for sacrifice…. I say solemnly that the Prime Minister should give an example of sacrifice because there is nothing that can contribute more to victory in this war than that he should sacrifice the seals of office.” Chamberlain resigned the next day, and Churchill became prime minister.

On June 19, 1940, Lloyd George was asked to join the Cabinet, and he refused. My mother wrote to him from school begging him to reconsider, and asking why he was staying out when his contribution was so vital. Lloyd George replied that he was unhappy with the way the war was being fought and felt he would be powerless within the current Cabinet. He probably thought he should stay available to provide alternative leadership if required. In the meantime, as he aged, he became happier to spend time on his farm in Surrey.

In 1945 Frances, left, and Jennifer, 15, stand in the doorway of Ty Newydd, the house where Lloyd George died.

In 1941 Margaret Lloyd George died, and in 1943 Frances finally became Lloyd George’s wife and publicly nursed him through his final illness. He died in 1945.

For the 30 years, she was a widow, Frances’ greatest pleasure was still talking about David Lloyd George, explaining his ideas and helping historians in any way that she could. She set up a museum about him in Wales and, as an old lady, she brought history alive for her granddaughter.

Read more

* Originally published in 2005.

Comments