The Llangollen International Eisteddfod is famous around the world for a reason

The River Dee rushes into Llangollen, racing around the rocky riverbed and speeding under the medieval bridge. The train at the riverside station snorts steam and chuffs off up the valley. The streets are bustling, too, as people fill their baskets at the butchers and bakers, or poke around for bargains on market stalls.

Visitors cross the bridge on their way up to the canal to see the narrowboats and the horses that pull them. Others head to the elegant ruin of Valle Crucis Abbey or to Thomas Telford’s soaring Pontcysyllte Aqueduct or the old farmhouse extravagantly bedecked by two 18th-century women who eloped together and won fame as the Ladies of Llangollen.

Read more

The happy activity is the stuff of everyday life in this tiny Denbighshire town, population of 3,412. Sited where the river, and later the road and railway, cut through the Berwyn Valley, it has long attracted residents, visitors, and merchants. Monks came in the Middle Ages seeking a remote site for their abbey. Later, stagecoaches taking people to Ireland stopped on their way to the Holyhead ferry. 19th-century farmers brought fleeces to the woolen mills. Those mills and the monks and the stagecoaches have long gone, but their legacy keeps the town as vibrant as ever—and never more so than in early July when musicians and dancers from around the world arrive to compete and show their skills at the weeklong International Eisteddfod.

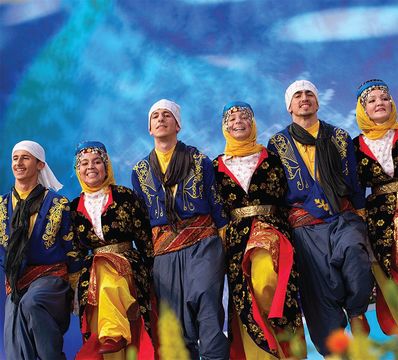

One highlight of the eisteddfod is the Tuesday evening parade through the grey stone streets. Morris dancers waving scarlet handkerchiefs clatter by. Then comes a troupe of Bretons dressed in somber black and flamboyant lace headdresses. Cheers greet the Ghanaian band dressed in orange and green dashikis, and the Irish dancers, whose crimson minidresses show off their fancy footwork. Some troupes twirl by demonstrating their steps; others throw candies to the kids. But all are thinking ahead to the time when they must perform before an audience and a panel of expert judges

Judges are essential to any eisteddfod. This Welsh word for “session” derives from “eistedd,” which means “to sit.” The people who do the sitting are the judges who listen, watch and eventually appear on stage to deliver frank critiques of every performance. Last year, the teens who dazzled audiences in the instrumental section were reminded, “The performance begins the minute you walk on stage.” The under-15 singers were advised that they should convey emotion. Dancers were warned that it was not just their choreography that counted, but their staging, which should reveal the role of the dance in the community.

Those black-garbed dancers from Brittany won the folk dance section with a dance that showed couples promenading, possibly to church, while the dancers from Northern Island, who performed immaculately, were downgraded for overemphasizing choreography. In contrast, a Welsh group was commended for its portrayal of village life with a dance that included a mari llywd—a mare’s head atop a pole used in traditional Christmas festivities. But they weren’t among the winners, because the judges thought their footwork lacked precision.

Nobody could fault the precision or staging of England’s Newcastle Kingsmen, a group of sword dancers who trailed into second place because their jeans-clad accompanists were not more integrated into the performance.

DANA HUNTLEY

Until the first International Eisteddfod in 1947, only Welsh writers and singers performing in their own language participated in an eisteddfod. Most were regional events—miners sometimes even held an eisteddfod in their mine—but the most important was, and remains, the National Eisteddfod. With these all-Welsh competitions as a model, Harold Tudor of the British Council suggested that bringing together amateur performers from around the world could help promote peace after the Second World War. Llangollen took up the challenge. Times were still bad in Europe in 1947.

Though local people offered to house competitors, how could they feed them in those days of rationed food? The Ministry of Food had to be persuaded to issue extra ration coupons. Then, a French rail strike in France threatened to strand many participants. Indeed, the Hungarian workers’ choir that eventually won had to hitchhike from Basle when their train through France was canceled.

Today the International Eisteddfod has a permanent pavilion and showground, but so many singers, musicians and dancers participate that local church and school halls host preliminary heats, and local people still provide accommodation. Indeed, the community is deeply involved at every level. For example, in 2011 Llangollen’s elementary school children took part in an evening performance of Benjamin Britten’s opera Noyes Fludde, whose libretto comes from a medieval play about the biblical story of Noah. The children sat at the back of the auditorium in their pajamas and bathrobes until it was time for Noah to gather the animals into the ark. Then, two by two, the little ones came forward bringing their soft toys—fluffy rabbits, long-armed monkeys, teddy bears—who played the parts of the animals saved from the flood.

Terry Waite, the Anglican peace activist, took the role of God. He’s certainly not the only famous person to perform at the eisteddfod’s popular evening concerts. Joan Baez and operatic stars Dame Kiri Te Kanawa and Wales’s own Bryn Terfel have given concerts in recent years. No star is more beloved in Llangollen than the late Luciano Pavarotti. Along with his father, he first performed at the Eisteddfod in 1955 as a 19-year-old member of Societa Corale Gioachino Rossini, a male-voice choir from their hometown of Modena. The choir won, and when Pavarotti returned to perform in Llangollen 40 years later, he said that early success had convinced him to pursue an operatic career.

The young Pavarotti stayed with a resident of Froncysyllte, which lies at one end of the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct. Having mugged up his English, he recalled his surprise at finding his hosts speaking Welsh. He must have also been surprised to discover that their house had a World Heritage Site on its doorstep. Designed by Thomas Telford and completed in 1805, the Pontcy-syllte Aqueduct carries the Llangollen canal and its traffic for 1,007 feet over the Dee Valley. The longest and highest (126 feet) aqueduct in Britain, it sped coal and slate from North Wales to the industrial towns of England. Though that trade is long gone, the aquaduct remains as busy as ever, because Britain’s canal-lovers enjoy nothing more than taking their boats over this most beautiful of engineering marvels.

You don’t have to own a boat to share the experience. You can take a two-hour trip starting from Llangollen Wharf, eating lunch or taking tea as you pass along flowery banks and soar over the aqueduct’s 19 pillars. Or you can simply drive to Froncysyllte and walk across. The views across the valley are glorious, and unlike boat passengers, walkers can take time to feast their eyes on the view or admire the intrepid ducks, who dive unfazed beneath oncoming boats.

While Pontcysyllte is a monument to Britain’s industrial age, the ruined abbey of Valle Crucis recalls earlier days.

Like Monmouthshire’s Tintern Abbey, it was built by the Cistercians. Typically, they settled in remote valleys, with grazing for animals and a river for drinking and power. From 1201, when they acquired the land, until 1536, when Henry VIII seized their monastery, the Dee and the nearby hills of the Horseshoe Pass served the monks’ purpose well. Today the elegance of the ruined east and west fronts of the abbey and glories of its setting make a soothing contrast to the bustle of Llangollen’s busy street.

The serene beauty of Valle Crucis draws many visitors to the next-door campsite. Indeed, Llangollen has a history of persuading people to stay a while. Among them were the Ladies of Llangollen: the Anglo--Irish aristocrats Lady Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby, whose friendship alarmed their families because it suggested that they would not marry. Various stratagems were attempted to keep them apart, but in 1778 they eloped, planning to live in England. Their route from Holyhead took them through Llangollen, which they found so alluring that they stayed and acquired a farmhouse.

Having refurbished the outside in black and white and the inside with Gothic-style wood and leather wall coverings, they renamed it Plas Newydd—New Place. Materials for their embellishments often came from their visitors, which included the Duke of Wellington, Sir Walter Scott, William Wordsworth and Robert Southey. Today Plas Newydd is a museum with many of the ladies’ furnishings and bibelots, and guided tours telling visitors about the singular women and the maid who helped them.

They are buried in a single grave at 13th-century St. Collen’s church, whose square Victorian tower rises above the roofs of the town. It’s dedicated to a 6th-century Celtic saint who killed a murderous giantess who lived on the Horseshoe Pass. Long after the giantess’ day, the pass had slate mines, and in the 19th century, a road followed a horseshoe-shaped route into Llangollen so the slate could be shipped along the canal. Today the 1,368-foot-high Horseshoe Pass is home to heather and sheep. They gazed curiously at the humans who stop to admire the vistas before entering the town named after the saint who killed the local giantess: “Llangollen” literally means “Collen’s church yard.”

Having been saved from the giantess, Llangollen still seems to be blessed. It has both the riches of its history and the modern energy that created the International Eisteddfod and more recently, the annual October Llangollen Food Festival. It features cookery demonstrations, a beer trail around Llangollen’s many bars and pubs, and the products of inventive food makers. In 2011, an Anglesey ice-cream company highlighted their newest flavor: Hellish Relish. Powered with chili and spices, it sounds like something cooked up by the ancient giantess, but along with other good local fare it’s just one of the many vivid elements in the mosaic of this most interesting of little towns.

COURTESY OF LLANGOLLEN INTERNATIONAL EISTEDDFOD

Comments