Jim Corbett reflects on all the barracks he has known and the life lessons he learned.

My soldiering days began, oddly enough, at school. In the 1960s, like many British schools, mine had a cadet force or Officer Training Corps as they were also known. My school experiences gave me two claims to fame. Firstly I believe I may be the last member of the British forces to have fired a Sten Sub Machine Gun.

Read more

The Sten was made very cheaply for five shillings during the first years of World War 2 and if ever the adage ‘you get what you pay for’ needed an example the Sten would be it. It was a nasty unreliable weapon that managed to fire bullets at right angles to the muzzle when it was not chopping off your fingers should they stray into the unprotected breech opening. We had one in the cadet force armory and one day came across some ammunition for it hidden in an old cupboard in the Tower of London. Yes really, that Tower of London. But that’s another story.

D-Day soldiers

Parachute Regiment

The second experience has stood to me for almost fifty years. At one summer camp at Crowborough Warren Camp in Sussex, we returned from a very muddy overnight exercise to be told we must send 10 cadets immediately on a coach for a visit to the Parachute Regiment Depot at Aldershot. So, tired and muddy as we were, we dumped our kit and clambered on to the bus. At Aldershot, we were met by a Para Corporal who commenced to march us across the parade square. After about twenty yards there was a noise like a bull bellowing and a jet taking off at the same time. The corporal promptly ran across to a corner of the square where stood a towering uniformed figure wearing a white Sam Browne belt.

I didn’t like the way this was shaping up. Another bellowing ended in a falsetto scream. I couldn’t catch a word so did what all good soldiers do and stood fast. Another scream followed from which I caught the words ‘Senior man there?’ Oh Lord, that was me. I stamped to attention and yelled ‘Sir !’ as loud as I could. This is a catch-all military phrase that means anything you want it to mean and answers all questions, even the ones you can’t hear. I certainly heard the next phrase which ended “…off my ******* square”. We needed no further bidding but took off like scalded cats.

As we perambulated around the depot visiting the 25 meter range, the assault course, and the Regimental Museum we, or at least I, bumped into this white belted figure several times. I’m sure you must have guessed but this was the Regimental Sergeant Major, RSM Dusty Miller. He excoriated my mustache, My appearance, my parentage, my closest relations. He taught me swear words I had never heard before nor since. He showed me that it was quite possible to have the skin flayed from your back by words alone. After two hours I was a broken man.

At last, the time came for us to return to camp and I slunk on to the coach with admiring glances from the other cadets who knew I had taken one…or maybe a dozen, for the team. Just as I settled into the plush seat the driver leaned over and told me the RSM wanted to see me in his office. If I could have died then I would have succumbed gladly.

I knocked on the office door and entered. He sat massive, bull-like and the embodiment of threat, behind a desk which looked several sizes too small. He spent twenty seconds telling me what a disgrace I was, how I didn’t merit any rank, and how I had better shape up quick and now! Then he said, “Sit down son,” and gave me a cigarette, I didn’t smoke but I took it anyway and it saved my life. Mind you it took me forty years to give them up.

He told me how important it was to show your troops you were in control, how as a young soldier waiting to escape across the Rhine at Arnhem he’d watched his own Sergeant Major calmly polishing his boots and how such a mundane thing created an aura of calm and confidence in the worst of circumstances. What he taught in twenty minutes over a couple of cigarettes is priceless and has stood to me ever since. For there is a truth and a beauty in the experience of the infantryman which is every bit as valid in civilian life as in the military. Still, he is my hero.

Soldier

The Territorial Army

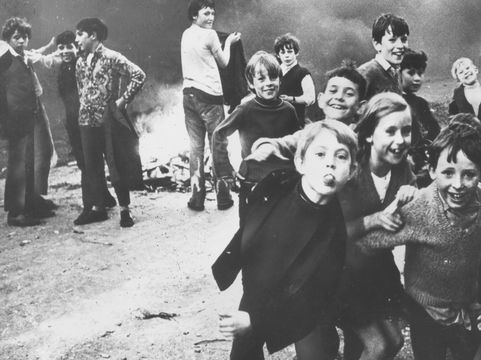

Largely as a result of my cadet experience, I went on to serve for eleven years in the Territorial Army with a number of attachments to regular army units. I have visited barracks, army camps, and campsites across the UK and elsewhere and they punctuate my experiences. How I was chucked into a huge fire tank at Crowborough Camp for a laugh; stood next to a man who was hit in the eye by a ricochet on an army range in Suffolk; took my turn on sentry duty in the middle of the Black Forest with a fully loaded rifle against the vague possibility that the Soviets might appear but the greater chance of a wild boar trying to savage me.

I have heard ghostly footsteps in the dead of night in a First World War vintage sickbay at Okehampton Camp on Dartmoor and again in an ex SS barracks near Dortmund. I have spent the night in water-filled trenches, most of which I dug myself, from Wales, via Dartmoor, Cultybraggan in Scotland, St Martin’s Plain in Kent, and the North German Plain to the central Highlands of Cyprus. I have driven Landrovers, Bedford 4 ton lorries, Armoured Personnel Carriers, a tank, and a fast patrol boat. I have flown in helicopters, light observer aircraft, a Jaguar Fighter Bomber and an old DC3 Dakota. I have fired the aforesaid sten, the Bren Gun, General Purpose Machine Gun, 2-inch mortar, Self Loading Rifle, Lee Enfield Mark 4 rifle, Browning and SIG pistols, the 84mm Carl Gustav anti-tank weapon, a 3.5-inch Rocket launcher, and a signal pistol.

Yet in all this time I never fired a shot in anger, I have been shot at but never returned fire. That is because during my time in the seventies the British army had no major campaigns to fight until the Falklands War in 1981 but few reserves were called up for that one. There was Northern Ireland of course and various Special Forces campaigns in the Arabian peninsular and the jungles of Borneo and Malaysia but I took no part in any of them.

Someone once asked me if I regretted not seeing proper action and my answer was that I regretted not being tested. But the experience was nonetheless invaluable. I suspect I understand my strengths and weaknesses better than most. I know how far I can, or could once, march in a day (56 miles). I have a few fears, I know how to look after my family, I can read a map like a book and navigate without satellites. Above all else, it made me resilient and I cultivated Dusty Miller’s doctrine of being calm in a crisis. That came in handy on many occasions in my subsequent career in hospitals. Sometimes people will try to bully or insult me. When that happens I fix them with a steely glare and just say, “I’ve been insulted by experts and I include the RSM of the Parachute Regiment in my experience, you don’t come close.” It never fails.

Comments