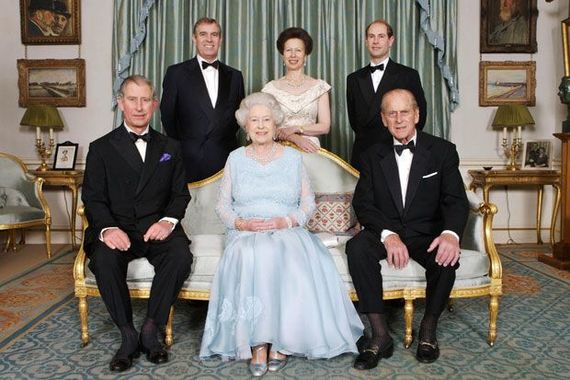

HRH Queen Elizabeth II.Getty

Queen Elizabeth II was the world's longest-reigning monarch but what comparisons can be made between her reign and that of Queen Elizabeth I?

Editor's note: Queen Elizabeth II, Britain's longest-serving monarch passed away on Sept 8, 2022, aged 96. Now, BHT takes a look back at some of the most popular stories which arose during her 70-year reign.

When a youthful, pretty Elizabeth II acceded to the throne in 1952, she was hailed by newspapers as a fairytale queen, “the hope of our nation.” And who can deny the glamor and spectacle of carriages and costumes at her coronation the following year? Here was a “New Elizabethan Age” that promised to chase away the shadows of postwar gloom.

Beneath her flowing frocks of state, Elizabeth herself seemed to have kept her feet firmly on the ground, and she took a rather less than twinkly view of her Tudor namesake, whose reign is celebrated as a Golden Age of British history.

“Frankly,” she intoned in her second Christmas broadcast to the nation, “I do not myself feel at all like my great Tudor forebear, who was blessed with neither husband nor children, who ruled as a despot and was never able to leave her native shores.”

Fast forward six decades, will history judge her reign to have shone as brightly as Elizabeth I’s Golden Age?

THE GRANGER COLLECTION, NYC

The reign of Queen Elizabeth I

Tudor Elizabeth’s path to the throne had been fraught with danger. Declared illegitimate following the execution of her mother, Anne Boleyn, she was raised a Protestant and endured imprisonment in the Tower of London during her Catholic sister Mary’s reign. When Elizabeth became Queen in 1558, she was welcomed with enthusiasm by a nation sick of “Bloody Mary’s” persecutions.

The challenges she inherited were breathtaking, not least how to rule as a 25-year-old woman in a man’s world. Capricious and headstrong, Elizabeth had nevertheless honed her survival skills. Urged to marry and produce an heir, she preferred to coquette with grandees at home and abroad: The royal hand was coveted, but never won. She presented the selfless image of the Virgin Queen, married to the throne and her nation. Elizabeth also had a great talent for surrounding herself with clever, accomplished ministers.

In religious matters, Elizabeth sought a “middle way” between the rampant Protestantism of her brother Edward VI’s reign and the rabid Catholicism of Mary’s rule. Compromise suited extremists on neither side of the ideological divide, and her reign was barbed in part by conspiracies and persecution. Nor did Good Queen Bess shrink from signing the death warrant for Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, after the latter had been implicated in treasonable plotting.

This hand-tinted illustration depicts the “invincible” fleet of ships comprising the Spanish Armada. The original hangs in the National Maritime Museum PHOTO©PHILIP MOULD LTD, LONDON/THE BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY

All the while, England continued to expand its influence, through voyages of discovery, trade, and piracy, encouraged and sometimes financed by the queen. Sea captains and adventurers like Francis Drake, who circumnavigated the world, and Walter Raleigh, who organized expeditions to North America, sprinkled a salty shimmer of derring-do across the times.

When England faced Catholic Spain’s “invincible” Armada in 1588, Elizabeth the Warrior Queen famously addressed her troops at Tilbury: “I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a King, and of a King of England, too; and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain or any Prince of Europe should dare invade the border of my realm.”

Her fleet, and the weather, defeated the Armada; Elizabeth “ruled the waves.” Feast your eyes on George Gower’s iconic Armada Portrait that hangs at Woburn Abbey in Bedfordshire, showing the Queen resplendent, her hand on a globe, pointing symbolically to Virginia, while the doomed Armada sails behind her imperiously coiffed head.

Elizabeth was the mistress of spin, all right, and there were plenty of adoring subjects ready to polish her image. Edmund Spenser portrayed her as Gloriana in his Faerie Queene and Shakespeare entertained her. She patronized composers such as William Byrd and Thomas Tallis, and the arts flourished.

Elizabeth paraded her dazzling image around the country on her famous annual progresses, and the crowds lapped it up. Wealthy hosts at stately homes were less joyous, often finding the costs of hospitality ruinous.

Elizabeth’s Golden Age lives on, too, in the great prodigy houses built by those who prospered, like Hardwick Hall, “more glass than wall,” in Derbyshire. Yet a lot of many folks went unimproved; dingy dwellings, the threat of plague, bad roads and economic depression in the 1590s made life a struggle. Elizabeth herself left large debts to her successor, King James I.

Yet, history paints a kind picture. It forgets the vain, hook-nosed old biddy of later years that wore a wig, whitened her face and applied urine to try to erase the wrinkles. History remembers Elizabeth’s Golden Speech before the House of Commons in November 1601, scarcely 16 months before her death at 69. “There is no prince that loves his subjects better, or whose love can countervail our love,” she trilled. For such a brilliant self-publicist, so in touch with her times, it is no wonder she became a national treasure and her 44-year reign, a Golden Age.

Queen Elizabeth II

Leap forward again to Elizabeth II, who, like her namesake, was 25 years old when she became Queen on the death of her father in February 1952. This Elizabeth, too, was welcomed to the throne, though for very different reasons and by a very different world.

Hers had been a stable upbringing with her younger sister, Margaret, in a tight-knit family: “We Four,” as King George VI had fondly called his brood. Such an idyllic family image restored the nation’s faith in the monarchy, coming on the heels of the constitutional crisis provoked by uncrowned Edward VIII’s abdication in favor of marriage to divorcée Wallis Simpson in 1936.

Elizabeth II, conformist, conservative and with a deep sense of duty, was determined to consolidate the gain. Her coronation in 1953, televised for the first time, was a glorious affair, the Queen radiant amid her young family, which already included Charles and Anne.

Both Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Victoria had set the bar high as icons of female leadership, and Elizabeth II didn’t have to contend with all those concerns over “female weakness” that troubled previous ages when might equalled right. Twentieth-century monarchy meant she was constitutional sovereign of a democratic United Kingdom, and she took on an awesome array of responsibilities: Head of State and the legislature, Head of the Church of England and Armed Forces, Head of State of the overseas realms and Head of the Commonwealth, not to mention chief ambassador for the UK and figurehead of a top tourism brand.

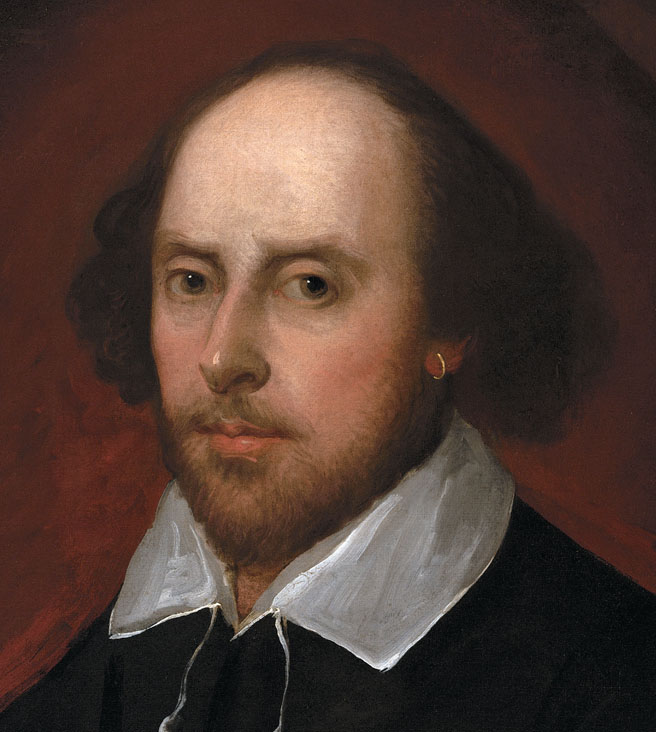

Elizabeth I’s Golden Age in the arts is best symbolized by the iconic William Shakespeare CORBIS WIRE/WONG MAYE-E

Sovereignty may have been shorn of executive powers over the centuries in favor of a more symbolic role, but Her Majesty ploughs through Red Boxes of documents regarding matters of the state most days. She may encourage, warn and be consulted by Government, but she must remain politically neutral, and all British prime ministers—12 different ones have come for weekly audiences over the years—speak of the wise experience she brings to national and global problems.

As others pass by, the Queen has represented stability and continuity, a focus for national identity—now there’s a shape-shifting beast—unity and pride. She heads up the pomp and splendor of traditions like Trooping the Colour, and confers a regal air to all the big occasions like the State Opening of Parliament. Quite what she thinks of devolution of political powers to the Scottish Parliament and Welsh Assembly, she keeps hidden behind that dignified smile.

The Queen has proved particularly passionate about her role as Head of State of 15 Commonwealth realms (in addition to the UK), and Head of the Commonwealth itself, embracing 53 independent countries. While many have grumbled about ridding themselves of vestiges of Empire, Her Majesty continues to apply the royal glue and, more often than not, her visits go well. Indeed, she has traveled the world on a scale unparalleled by any preceding sovereign, touring for months at a time to represent Britain. In her Golden Jubilee year of 2002, she circumnavigated the globe, the sixth time she had done so in a single tour.

At home, she takes public visits seriously, too, and has some 430 public engagements a year. If she loses interest in opening yet another venue, she never shows it. She has been the person to crown moments of national triumph: from presenting England’s soccer team with the World Cup in 1966 to holding a reception for the country’s Rugby World Cup winners at Buckingham Palace in 2003. When disaster strikes, she has been there to channel public grief: from visiting Aberfan in south Wales after the slag heap disaster that killed 144 people in 1966, to attending a service of remembrance at St. Paul’s Cathedral for the victims of the July 7 London bombings in 2005. Both her son, Andrew, and grandson Harry have seen active service, in the Falklands War and Afghanistan, and she has shared her subjects’ hopes for safe returns.

As Head of the Church of England - a role cobbled together by her Tudor forebears amid much religious strife - she is devout in her calling. With a nod to modernity, she “recognizes and supports” other faiths in a changing, multicultural Britain. She long ago stole a march on David Cameron’s Big Society idea: she is patron of more than 620 charities and organizations.

There is no doubt that the Queen has presided over revolutionary times, socially, politically and technologically. Now, even the monarchy is on Facebook. Quite how the UK’s multicultural society will pan out, how they move from a manufacturing to a services economy will shape up, or how history will contextualize modern architecture and arts—urban regeneration, John Betjeman, Francis Bacon et al.—can not yet be judged. For sure, general living standards have improved more during the time of Elizabeth II than of Elizabeth I.

And so to the Royal Family and the greatest crises of the Queen’s reign, the point and cost of it all. From the outset, the image was sold of a happy family monarchy, though the affectionate “We Four” has become the more businesslike “The Firm,” and for no little reason. It is estimated the Royal Family has a “brand value” of £5 billion. Yet, in this age of shrill scrutiny and lack of deference, the cost to the taxpayer is constantly questioned. An uproar followed the suggestion that the public would fund repairs to Windsor Castle following the 1992 fire, for example. Instead, Buckingham Palace was opened to summer visitors to help raise cash, a move so popular that it has continued.

Concessions have been made - the Queen now pays tax on her personal income, the royal yacht Britannia was decommissioned - and recent accounts (it’s all “transparent” these days) show the Queen reduced the overall bill for the monarchy during 2009/10 by £3.3m, from £41.5m to £38.2m. The royals now cost each person in the UK, “shareholders in The Firm,” around 62p - less than a loaf of bread. Further cuts are promised, but how much stardust can be shed before the Crown loses its luster?

“Image management” has been a huge problem. The 19th-century writer Walter Bagehot famously warned that the monarchy should “never let daylight in,” and the Queen, one suspects, agrees, while modernizers (including Prince Philip) have argued for greater accessibility. The Queen was reluctant to allow TV into Westminster Abbey for her coronation, lest the occasion is trivialized; in that, she was wrong. Other PR exercises have been disasters, notably, the documentary Royal Family screened in 1969, which revealed the royals in cringe-making scenes around the breakfast table: ordinary people devoid of mystique - a reinvention that bombed.

The genie was out of the bottle, though, and the long lenses of the paparazzi have considered the royals fair game ever since, most cruelly exposing the disintegrating marriages of the Queen’s children. Anne, Andrew, and Charles have all been mired in divorce; in fact, the Queen required Charles and Diana to divorce after they separated, to put an end to their damaging bickering and revelations of affairs. How times change.

Does the nation expect exemplars of morality or a royal soap opera? The only time the Queen’s emotions slipped in public occurred in the 40th year of her reign, as three marriages and Windsor Castle were going up in smoke. She called it her annus horribilis and pleaded for public criticism to be leavened by kindness.

Worse came. When Princess Diana was killed in the Paris car crash of 1997—charismatic, touchy-feely, volatile Di, so in tune with the times - the Queen and Palace were slow to put their grief on public parade, and the public didn’t like that at all. The Queen later admitted to the nation that there were “lessons to be drawn from Diana’s life and from the extraordinary and moving reaction to her death.”

Elizabeth II is actually a shy and intensely private person, a countrywoman who loves horses and dogs. It’s said she is a good mimic. She likes Scottish dancing. But she prefers to remain enigmatic in public, to preserve the mystery of sovereignty. The fact that she hasn’t changed is both a great strength and a weakness.

It is easy to look back to Elizabeth I’s Golden Age and celebrate the shiny highlights; less easy to predict what will really matter in the long run when a reign is ongoing. Elizabeth I seemed to personify her times: flamboyant, progressive, ruthless, strong. Elizabeth II has always seemed old-fashioned but has maintained a reassuring rocklike stance in a cynical, runaway world.

* Originally published in July 2016, updated in Sept 2022.

Comments