A quirky interlude in the Marcher Borderlands. “Queen sells church for £1” is one of the more curious newspaper headlines back in 2015.

This strange headline was all the more so because the chapel in question is just a short jaunt from two of South Wales’ most charismatic medieval attractions, Chepstow Castle and Tintern Abbey. Curiouser still, the forgotten ruin of St. James’s at Lancaut even has links to its famous neighbors—offering a quirky interlude to add to an itinerary from Chepstow, the gateway to the Marcher borderlands of England and Wales.

While 18th-century devotees of the Picturesque Movement that worshipped all things wild, romantic, and ruined would have viewed St. James’ while gliding past on fashionable Wye Valley riverboats, today it’s a walk or a drive from Chepstow’s market town. A six-mile Lancaut Loop hike, not for the fainthearted or weak-kneed, takes in sheer limestone cliffs and dramatic vistas. Or simply drive a couple of miles to Lancaut and ramble the signposted track plunging through woodlands to the most tranquil of church settings in the Wye gorge.

Read more

St. James'

St. James' stands roofless in splendid isolation, eerie traces of the abandoned medieval hamlet that it once served discernible only as bumps in the riverside fields. James Chapman, chairman of Forest of Dean Buildings Preservation Trust, told me that the neglected church had become “ownerless” and through the old feudal system of escheat reverted to the Crown. By petitioning the Queen to create a new title to the church, the Trust was able to buy it for a mere £1 from the Crown Estate. Legal bills at £2,500 were less of a bargain, and the Trust estimates £40,000– £50,000 for immediate conservation works.

Why bother, apart from maintaining the Wye Valley’s tradition of the Picturesque? Because the Grade II-listed building has such tremendous historical interest and should be preserved for future generations, Chapman says. A Celtic chapel was sited here as early as AD 625, dedicated to an obscure Welsh saint, Cewydd. Set on a peninsula loop of the River Wye, it was also in a strategically important—and dangerous—position. Offa’s Dyke cuts between England and Wales nearby, and from the 11th century conquering Normans advanced into Wales from bases like Chepstow Castle. Lancaut was on the Welsh side of the border until the late 10th century, on the English thereafter.

Chapman thinks Viking incursions destroyed the original chapel. St. James’ dates from circa 1120, built according to one theory, by a lord of Striguil, as the Normans called Chepstow. Indeed some of the stone used for St. James’ seems to have come from Chepstow Castle during rebuilding work there, and Lancaut was the site of a leper colony or infirmary for the castle.

The settlement at St. James’ has also been linked to Tintern Abbey, a foundation endowed by successive lords of Chepstow Castle. Research by Chapman and the Trust aims to clarify claims—and investigate counter-claims that, on the contrary, St. James’ belonged more to the spread of Celtic chapels up the River Wye. Whatever is revealed, stories of war and peace, of marriages of ancient and arriviste new cultures are the warp and weft of the Marcher lands, and the thread is the River Wye: bringing troubles and trade-in equal measure throughout history.

Chepstow

Back down in Chepstow, the castle dominates the town and visitor interest. The country’s oldest stone castle was built just after the Battle of Hastings by William Fitz Osborn, one of William the Conqueror’s closest and wealthiest allies. Towering above the River Wye on its draughty cliff, it was perfectly sited for supplies by ship—at 40 feet the Wye has the second-highest tidal range in the world—as well as to fight the Welsh.

The impressive ramparts of Chepstow Castle guard the entrance from the Severn Estuary into the River Wye.

From 1067 to 1690, successive owners pursued the latest fashions in military architecture: “the greatest knight” William Marshal’s massive main gatehouse built to a revolutionary design, with two towers, arrow loops, murder holes and portcullis, and the 5th Earl of Norfolk’s 13th-century palatial apartments.

The only real military test to the castle came during the English Civil War when it was besieged in 1645 and 1648, and fell to Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarians. The castle’s garrisons finally left in the 1680s and the great edifice fell slowly into ruin, to be rediscovered a century later when William Gilpin, the high priest of the Picturesque Movement, published his Observations on the River Wye (1782), creating the craze for Wye Valley tours that has long outlived him. Chepstow Castle Inn and Castle View Hotel were converted from townhouses to serve growing visitor numbers, and those pubs, tearooms and accommodation remain in fair supply around town today.

As gateway to the Wye Valley, Chepstow has long fed and lodged visitors.

Key to understanding Chepstow and its history is that the whole region was ruled from Chepstow Castle by the Marcher lords uniquely created by William the Conqueror to defend and extend his borders from England. As long as they stayed loyal, these lords ruled independently over their territories, with their own armies, courts, laws and powers to impose taxes. When Roger Bigod constructed the 15-feet high town wall—large stretches are still here, with several stocky round towers surviving and a town gate—it was as much to ensure traders coming and going to the market paid the lord’s dues as to defend against the marauding Welsh.

Exempted from paying duty to the Crown, Chepstow flourished as a peacetime port. Drop into Chepstow Museum opposite the castle, and displays reveal more about the privileges of the Marcher lords, finally abolished in the reign of Henry VIII, as well as the prosperity brought by shipbuilding and salmon fishing. Tourism and bridge building are two further leitmotifs: the current cast-iron Old Wye Bridge of 1816 is at least the sixth bridge on the site; halfway across, you pass from Chepstow and Wales to Gloucestershire and England.

Visitors to Tintern Abbey relax today in the beer garden of the Anchor Inn on the grounds of the picturesque medieval monastary.

What else to do in Chepstow?

There’s a riverside walk and town trail for architecture buffs, while Beaufort Square, with its artworks, is the area to people-watch. Pedestrianized St. Mary Street is the place for cafés, while Chepstow Racecourse is the venue for a flutter.

Do also visit the Priory Church of St. Mary, a place of Christian worship for more than 900 years. The early 12th-century arched doorway with characteristic zig-zag decoration remains a wonder.

Warmongers and the wealthy, it seems, have always been eager to make down payments on a blessed afterlife through the foundation of religious houses, and that’s certainly also true at nearby Tintern Abbey, whose great benefactors included lords of Chepstow Walter de Clare, William Marshal, and Roger Bigod. Of course, such benevolences were cultural expressions of conquest, complementing castle and sword, as well.

Tintern Abbey

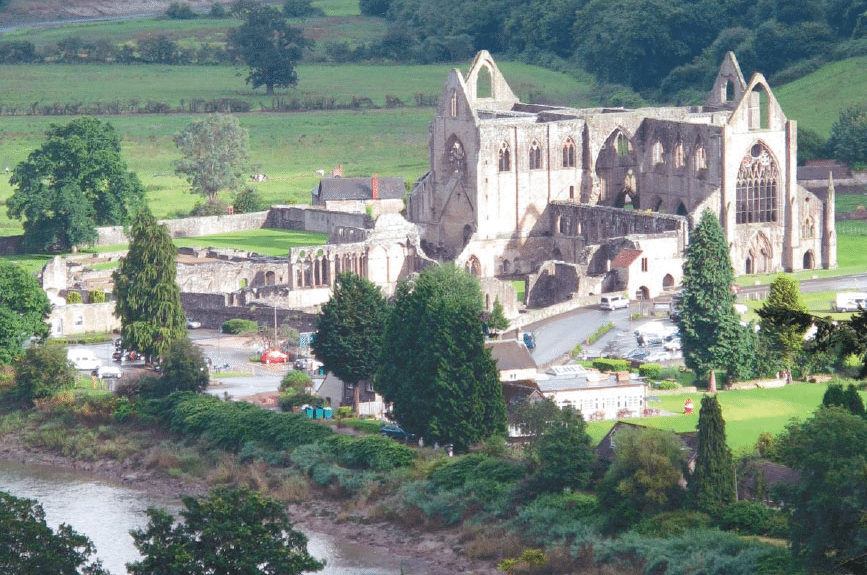

You can reach Tintern Abbey from Chepstow along the Wye Valley Walk, or sit back and enjoy the scenic five-mile wooded drive north along the A466. Begun in 1131 and dissolved by Henry VIII in 1536, the abbey was only the second Cistercian foundation in Britain and the first imported from France to Wales. Ever since painter J.M.W. Turner captured the ruin in watercolor and William Wordsworth composed his lines to the “sylvan Wye” during his 1798 tour here, the abbey has been a honeypot, picturesque destination. Early morning is best to catch the peacefulness that attracted the White Monks, walking within the shadows of the sublimely soaring Gothic church and cloister remains.

The Anchor Inn, within the abbey’s original grounds, and the Abbey Mill on the site of the monks’ original corn mill, both offer welcome refreshment, and along the river, Tintern Old Station, where rail-borne Victorian tourists once alighted, is now a pretty spot for a cream tea.

The village of Tintern Parva sweeping along the Wye’s banks is a quaint bumble with superb bookshop and more inns, and above the abbey amid trees is the ruin of St. Mary’s Church on the site of a chapel that served as a retreat for the monks. Medieval St. Michael’s Church whispers—like St. James’s at Lancaut— vernacular tales that pre-date the Norman-era grandeur of Chepstow Castle and Tintern Abbey. Put these hidden gems on your itinerary, too, if you’ve time, all pieces in the jigsaw broken and remade when the Normans arrived.

Getting to Chepstow

Take the train to Chepstow from London Paddington via Newport, journey time circa 2.5 hours. By road, head west on the M4 to the Severn Crossing (about 120 miles).

For Chepstow, see www.chepstow.co.uk. St. James’ Church is a two-mile drive up the B4228 to the village of Woodcroft, then turn left following signs to Lancaut and walk (50 minutes) down through Lancaut Nature Reserve.

Tintern Abbey is 5 miles from Chepstow along the A466, www.cadw.wales.gov.uk.

* Originally published in July 2015.

Comments