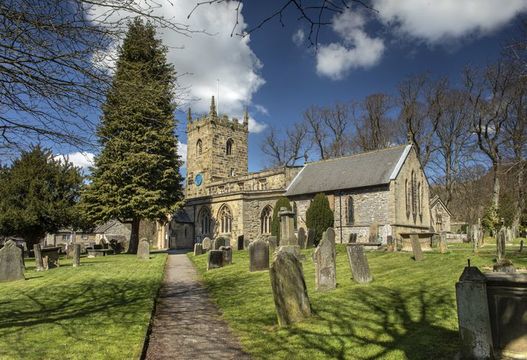

Eyam.Getty: Images

Dana Huntley looks at the history of the Derbyshire village of Eyam, whose community sacrificed to stop the plague’s spread

In 1665, the bubonic plague raged across Europe to Great Britain. The terrifying disease’s arrival on English shores was nothing new. Called the Great Plague, this was the last of the periodic eruptions of the Black Death pandemic that decimated the populations of Europe and Great Britain for 400 years. The bacterium Yersinia pestis is believed to have originated in China in 1331 and migrated west along the Silk Road. The fatal disease reached Western Europe in full force in the late 1340s, striking England in 1348.

Before the Black Death abated, over the next few years the bacteria brought death to a third of Europe’s population and took half of the people in densely crowded cities such as London. Across the English countryside, whole villages were virtually wiped out, their few remaining survivors taking refuge in neighboring communities. Over time, the physical remains of the deserted village dissolved into the earth and the place name was erased from maps and forgotten. There are countryside vistas today, particularly in East Anglia, where across the flat fields stands a small stone church, seemingly in the middle of nowhere. The Norman parish church was many times the only stone structure in a village that disappeared in the 14th century.

Across Europe and the Middle East, plague epidemics flared often over the next centuries. London itself had seen several outbreaks in the early 1600s. Then came the Great Plague.

Great Plague hits London

In 18 months of 1665-1666, the Great Plague claimed the death of 100,000 Londoners – estimated at nearly one out of four people. Daniel Defoe recorded death’s ravishment of London in his evocative Journal of the Plague Year. Samuel Pepys described it in daily detail in his diary.

The vector of this fatal bacteria was fleas that lived on black rats. In the 17th century, not unlike other large cities of its time, London was a crowded, walled metropolis teeming with people, most of them dirt poor. The city’s narrow streets and the roads leading into London’s six city gates bore a constant, jostling mass of wagons, horses, carriages and pedestrians. In ramshackle suburbs and crowded slum tenements many families lived in a single room. Muck and slops filled the narrow streets and the fuel for cooking or heating was high sulfur coal. Clean water and sanitation of any kind were non-existent, as was any space for social distancing. What the city had in abundance was rats. What the rats had in abundance was fleas.

Reports of the plague on the continent began arriving in London in the early 1660s. There was no way of preparing for the epidemic to come. No one knew how the disease was transmitted or caused. Nor could much have been done had they understood. There were no antibiotics or efficacious drugs of any kind. There was certainly no place to quarantine an infected population the size of London’s.

Apparently, the plague arrived first in the London docks on a Dutch merchant ship in the spring of 1665 and took its first hold in St. Giles-in-the-Field, a crowded slum suburb just outside the city gate. With only a four to six-day incubation period, the disease quickly spread throughout the London metropolis. During the summer months the plague raged, and the death rate rose. When plague was found in a house, a red cross was painted on the door and it was nailed shut trapping all those inside and condemning them to the painful death. Corpses were removed from doorsteps at night and unceremonious buried in “plague pits.” The situation was grim.

Lawyers, merchants and peers – anyone with means and a destination – fled the stricken city. King Charles II and his court left for Hampton Court, eventually taking refuge in Oxford. Parliament followed and sat that October in Oxford. London and its poor were left to their fate. Samuel Pepys records on October 16th: “How empty the streets are, and melancholy, so many poor sick people in the streets, full of sores, and so many sad stories overheard as I walk. . . . And they tell me that in Westminster there is never a physician, and but one apothecary left, all being dead.”

The pestilence spreads to the peaks

Of course, it was impossible to confine the disease to London. The Great North Road from Scotland and major arteries from East Anglia, the west and the south coast supplied the city with most of its food and goods and carried back the plague. Late that summer, a bale of cloth, perhaps cargo from a continental ship and unknowingly infested with plague-carrying fleas was sent to a tailor in the Derbyshire village of Eyam, six miles north of the market town of Bakewell. The tailor’s assistant, George Viccars, opened and aired the parcel, unleashing the bacteria-ridden fleas. Less than a week later, on September 5, 1665, Viccars was dead and others in the household soon followed.

Dozens died in Eyam over the coming autumn and winter. Those left by spring prepared to flee for their lives. The new parish rector, Rev. William Mompesson, and the previous pastor Thomas Stanley (removed because of his Puritanism) developed a plan to fight the contagion and convinced the understandably reluctant survivors to agree. The village would practice “social distancing.”

Among the steps villagers took was to hold church in the open air. They gathered for worship just a short walk from the village center at a natural amphitheatre called Cucklet Delf and stood separated in family groups at a distance from each other. Burials in St. Lawrence churchyard ceased. Each family would bury its own dead to minimize the plague’s contagion.

Most drastically of all, however, they agreed to completely quarantine and enclose the village to keep the plague from spreading to other villages and nearby towns of Bakewell, Sheffield and beyond. None would be allowed to leave or enter Eyam. The Duke of Devonshire, who owned much of the surrounding region, agreed to supply Eyam with food and other necessities from his Chatsworth estate just a few miles away. All transactions were done at the edge of the village; there was no person-to-person contact.

By August 1666, the contagion reached its peak – a half dozen people a day were dying. One woman, Elizabeth Hancock, is recorded as burying her husband and six children in a span of eight days. That same month Rev. Mompesson’s wife died and he buried her alone in the churchyard. Mompesson believed he himself would inevitably die in pain. But he did not.

Through September and October, the plague had run its course and new cases fell off. The last Eyam villager thus to die was Abraham Morten, a farm laborer, on November 1, 1666. In 14 months from the plague’s arrival, of an estimated population of 350-500, the St. Lawrence parish records identify 260 people from nearly 80 families who died from the plague.

Eyam’s self-imposed quarantine had worked. The sacrifice of the Eyam people did keep the bubonic plague from spreading beyond the village. It is impossible, of course, to know ultimately how many lives were saved, but historians agree that it must have been thousands.

Rural track near the village of Eyam in the Peak District national park.

Visiting Eyam today

On the A623 in the Derbyshire Dales, Eyam lies within the Peak District National Park just a few miles from the market town of Bakewell. Today, the village of roughly 1,000 claims its history as its principal industry. The entire village is a living history museum where a few hours walk on the Plague Trail around town unpacks its remarkable story.

The perfect place to begin is the Village Plague Museum and 12th-century St. Lawrence Church. There is plenty of parking. Plague cottages along the street tell their families’ tale in plaques next to the door. In the fields along the back, you can find the home burial grounds of several families. A short stroll along a well-worn path leads into Cucklet Delf, where the St. Lawrence parish gathered to worship during those dark months of quarantine. On Church Street, and a commanding presence in the village, stands Eyam Hall. The Jacobean manor house has been in the Wright family since 1672.

At a break for refreshments or lunch, in The Square find the Eyam Tea Rooms and the Café Village Green. Or head for a pub lunch at The Miners Arms on Water Lane, built in 1630. The inn offers comfortable accommodation as well.

In the neighborhood

Nearby Bakewell has had a market since 1254, traditionally every Monday. It is impossible to miss the unusual five-arch 13th-century stone bridge across the River Wye. All Saints Church dates from Saxon times, complete with 10th-century Saxon crosses in the churchyard. Bakewell’s chief claim to fame, however, is culinary, as the home of both Bakewell tarts and Bakewell pudding, both rich with almond and jam. Three shops in town claim the original recipe. Among them is the Rutland Arms Hotel, a comfortable, classic 3-star market town hostelry.

Much of the countryside around belongs to Chatsworth, the estate of the Duke of Devonshire. Chatsworth House, known as the “Palace of the Peaks,” sits surrounded by 2,000 acres of Parkland in a 150-acre garden about three miles north of town. Plan at least a half day to visit, but don’t miss Chatsworth.

Comments