Enjoy the wonderful protected vistas around London.Loop / Pawel Libera

London’s protected vistas! No one had heard of him today, and back in 1937, not that many people knew who he was either. But the citizens of London owe W. Godfrey Allen the raising of a glass for an exercise of foresight that has kept our city beautiful for nigh-on 75 years.

Allen was Surveyor to the Fabric of St. Pauls, and it was he who first crystallized growing fears that views of the cathedral would be obscured by increasingly lofty structures. People had been getting edgy about the impact of tall buildings ever since new construction techniques had enabled giant art deco novelties such as the Unilever Building and Faraday House, but it was Allen who actually started working out what had to be done on a practical basis to ensure that progress didn’t throw the heritage baby out with the developer’s bathwater.

Allen surveyed all the remaining views of the cathedral, worked out the best ones and proposed areas of control, or “eight-corridors,” where developers would have to maintain those views. There was also a proposal for set-backs, where builders would have to make sure new construction allowed continued “slot-views” of the cathedral at ground level. In 1937 Allen’s proposals, now rather more sexily entitled “St. Paul’s Heights,” were submitted to the Corporation of London, which acknowledged them to be a good idea.

Read more

The City was a different place then. Most agreements, from financial deals to building regulations in those days were of the gentleman’s variety, with a handshake the most popular form of seal. St. Paul’s Heights were adopted, and, by and large were remarkably successful in keeping the buildings low in sensitive places. There were a couple of unsporting chaps who reneged, but given that the period immediately post-WWII saw the biggest redevelopment of the City since the Great Fire, Allen’s calculations proved effective—so much so that they are still with us, only slightly altered.

The argument of how to maintain London’s great panoramas came to a head with a rather unlikely piece of legislation. Up to the early 1950s, buildings were not allowed by law to grow any higher than the reach of a fireman’s ladder (indeed, London’s first skyscraper, the magnificent art deco London Transport Headquarters at St. James’s, was unable to use its top floors for many years because of this). In 1954 the London Building Act was amended so that firemen would be allowed to use elevators. With that restraint lifted, the only thing stopping developers from engulfing London was legislation, and not everyone thought that that was a good idea. Many wanted to see progress, wanted to see a modern, vibrant city unencumbered by the past. There has been a tug o’ war between the two sides ever since.

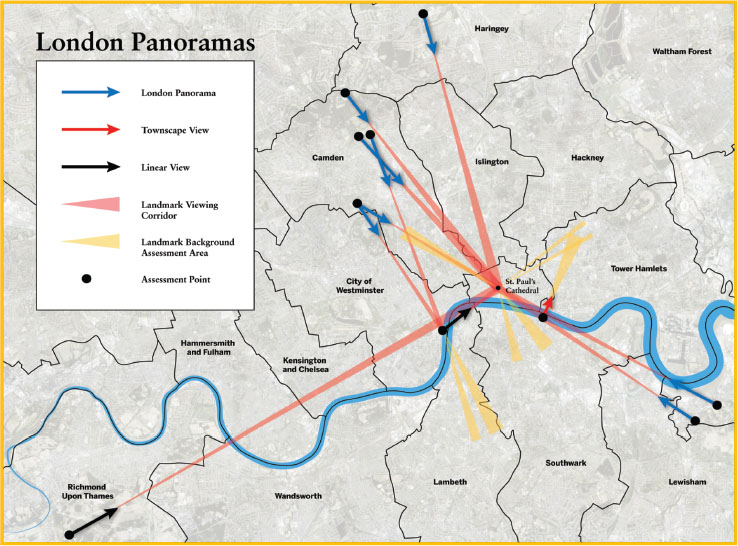

It would take a month of Sundays and a very boring list of inquiries, legislation, strategies, frameworks, initiatives, law suits, appendices and other governmental paraphernalia to go into what governs London’s protected views today (the book, produced by the Mayor of London for the use of developers, runs to 332 searing-hot pages of the very heaviest form of bedtime reading), but the upshot is this: There are 26 locations in the city where the public must be able to enjoy a clear view of landmarks (St. Paul’s Cathedral or other heritage big-hitters) without their being obscured or interrupted by tall buildings. Many of these locations are beauty spots in themselves, but a big part of their charm is in the panorama or vista that they frame.

Sometimes you’ve just got to have a clear view of St. Paul’s dome; other times, the backdrop or silhouette is included in the regulations.

Some of these spots are miles away from the City itself, and as can be imagined, developers hate them with a passion. They commission some world-renowned architect to design them a 40-story tower block in Bermondsey only to be told by Greenwich Council that picnickers in Blackheath can’t see the Old Bailey anymore.

Read more

But—what’s the point of having these protected views if we don’t enjoy them? Instead of just being a stick to hit developers, we should be using The Spatial Development Strategy for Greater London as a guidebook to the very best views to be had in town.

The 26 protected vistas are classified under four headings. Linear Views are just that—a line between two points that must not be crossed. The vista up the Mall toward Buckingham Palace and the line from Westminster Pier up to St. Paul’s Cathedral, for instance, are both officially protected. But there is, believe it or not, a regularly pruned hole in a hedge atop a Bronze-age barrow called King Henry’s Mount, in the middle of Richmond Park, through which any rambler who cares to do so, can spot St. Paul’s dome more than 10 miles away. To me, this is one of the most exciting of the statutory views, as it is somehow “secret,” an outdoor keyhole in the middle of a Royal Park that has been used by architecture lovers in-the-know for nearly 300 years.

The River Prospects are a series of excellent views of the Thames, principally from London’s best bridges, but also including the Victoria and Albert Embankments and the Jubilee Gardens in front of City Hall. It’s likely that many readers will have experienced at least some of these seemingly ephemeral vistas without realising that they are very carefully managed.

KEVIN JOHNSON

If you have ever taken a photograph of the Tower of London from across the river on the Queen’s Walk, snapped the view from the bridge over the Serpentine to Westminster, bought a postcard of Horse Guards via St. James’s Park or copied Canaletto and painted the view of Greenwich from Island Gardens, you will have the Townscape Views to thank. The third category of protected vista claims some of the most loved general scenes before the fourth and final section, the real heavyweights, the London Panoramas.

The Panoramas are truly breathtaking, usually high-up places from which the visitor just stands and wonders at the enormity and beauty of the capital, and I recommend a visit to at least one of these in any visitor’s stay. They really are worth it.

Alexandra Palace was built in 1873 as a northern counterpart to the Crystal Palace, which had been moved to South London. It’s fared slightly better than its more famous sister in that although it, too, has seen its fair share of fires, it has been restored and is now a fabulous late-Victorian pleasure palace set in massive parkland high on a hill. It’s currently an events venue; if you can get inside to the palm court, do try.

Apart from its own intrinsic interest and quirky 1930s additions from when it was used as a transmitter by the BBC, Ally Pally has sumptuous views from its gigantic balcony. It’s a doddle to get to, just a short walk from Alexandra Palace railway station—no need to ask directions, it will be very obvious where to go.

Parliament Hill, part of Hampstead Heath, is probably London’s most famous outdoor space, and it is always massively popular with locals. It, too, is easy to get to with Gospel Oak, Kentish Town and Tuffnel Park stations all very close. To me, it’s one of the less interesting places; you go there chiefly for the view and the lovely countryside. But it does throw up a real challenge for the city planners of tomorrow. London’s latest—and, by some way, tallest—new building, the Shard of Glass at London Bridge, isn’t finished yet, and already, if you view St. Paul’s from it, the cathedral nestles exactly within the silhouette of the new skyscraper. There were many objections to this building, because it directly challenged protected vistas and no one is really sure quite how they were overridden. Personally, I like the Shard very much. It’s a fantastic design, and beautifully delicate, but I worry that it has already set a precedent for other, less worthy constructions, whittling away at an already delicate planning system.

The avenue up The Mall toward Buckingham Palace is protected as a Linear View. LOOP IMAGES/MALCOLM PARK

If you’re only going to see one panorama, I’d recommend the one at Kenwood. Not because it’s necessarily the best (they’re all pretty spectacular), but because while you’re up there you can visit gorgeous Kenwood House, on whose grounds the viewing gazebo (a delightful little chinoiserie confection) stands. So you can see a grand, sweeping view of unusually undeveloped greenery, with the city in the background, and then float around a beautiful Palladian villa—before having a snackerel of something in the excellent tea rooms. It’s a bit of a walk from Gospel Oak or Hampstead Heath railway stations, but well worth it.

Primrose Hill is extremely popular. It’s very good for seeing the buildings close up—or as close as you’ll get while still keeping a big vista. When I was last there, they were busy trying to re-seed the grass after a winter of heavy snow had brought out every child and toboggan in the area; the scene must have been Christmas-card perfect (not that the kids would have noticed). Primrose Hill is an adjunct to Regent’s Park, so tubes to Camden or Chalk Farm are perfect.

There are two superb vistas south of the river, both in Greenwich. The most famous is just outside the Observatory, looking out over the Queen’s House, Greenwich Hospital, and, from there, the rest of London. In a planning anomaly from the 1980s, the London Dockland Development Corporation was given carte-blanche to build anything it liked on the old East End Docks. This led to a little colony of skyscrapers, the largest of which is the iconic Canary Wharf. Here, of course, protected vistas could whistle, and, if you stand on Greenwich Hill, the buildings at Canary Wharf lie smack in between the two Christopher Wren towers of the Old Royal Naval College. But you know what? Somehow, in some weird way, they work. I have come to love that view, modern building and all.

The final panorama, at Blackheath Point is by far the least-known of all the protected vistas. Even on a sunny day you’ll be likely to find at most a few kids kicking a football or an old chap with his dog. Cross the road out of Greenwich Station, head for the junction and ask a local. It rewards the sharp climb, the rural, overgrown country lanes and punishing last few steps with one of the best and most ancient scenes of all. This is where the Romans would have first viewed Londinium. And while you’re up there, spare a thought for the giant lost cavern (literally, they don’t know where the entrance is) under your feet, where once were held notorious masked balls and riotous drinking sessions.

There are all manner of fabulous vistas across London, and not all of them are protected. One such view is in the romantically overgrown Nunhead Cemetery in South London. Here, as well as rescuing cherubs and angels from the all-consuming undergrowth, a dedicated group of friends keep trimmed a view through the trees framing St. Paul’s Cathedral that is, I believe, one of the best sights in London.

More easily accessible is one superb example of a modern building sticking to the planning guidelines and being the greater for it. The new commercial complex at New Change, just east of St. Paul’s itself has a secret. If you go to the glass elevator and travel up (it’s free to all) you will have the most wonderful “slot view” of the cathedral. When you arrive at the top, there is a wide balcony, also free to the public, from which you can get a fabulous, close-up vision of St. Paul’s. If you don’t get to see any of the panoramas, this short detour is a must. W. Godfrey Allen would have approved.

Read more: Our favorite facts about The National Trust - preserving Britain's beauty

Comments