Jane Austen knew the Peak District and the journey of Ms. Elizabeth Bennett in Pride and Prejudice illustrates that brilliantly.

There are two famous shots in the 1995 BBC adaptation of Pride and Prejudice. One involves the then-unknown Colin Firth, a wet chemise, breeches, and riding boots. The other is far more evocative, when Jennifer Ehle, as Elizabeth Bennet, stands on the great rocks of what is now the Peak District National Park, contemplating the prospect of an awkward visit the next day.

It should have been so easy: A trip to the Lake District with her Aunt and Uncle Gardiner. Lizzie can’t wait. When business prevents her uncle from traveling so far north, however, they end up in the Derbyshire Peaks instead. Lizzie travels, desperate to avoid Mr. Darcy, and ends up in the Peak District location of his country estate, Pemberley.

DANA HUNTLEY

Jane Austen knew the Peak District. Pemberley might be fictitious, as is Lambton, the estate village, but the other places the Pride and Prejudice party visits are real enough, making following in Lizzie’s footsteps a tantalizing possibility.

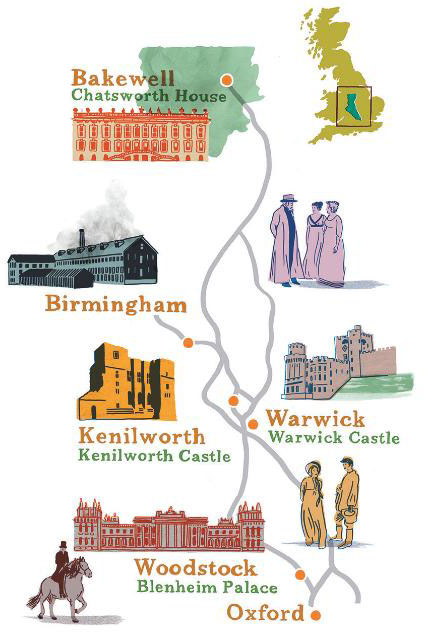

“It is not the object of this work to give a description of Derbyshire, nor of any of the remarkable places through which their route thither lay; Oxford, Blenheim, Warwick, Kenilworth, Birmingham, &c. are sufficiently known,” writes Austen.

Read more

And to some extent they still are. Oxford’s dreaming spires are as much on the tourist trail today as they have been since medieval times. The great castle at Warwick might not have had today’s commercial vision, but its stout walls, solid turrets and sumptuous interiors are essentially the same as Austen would have known them. The massive walls of Kenilworth Castle were romantic ruins for a good 150 years before Lizzie wanders their outlines.

Granted, Birmingham comes as a bit of a surprise on Jane Austen’s list of must-sees. While it might not seem much of a tourist attraction now, the city’s steam-fuelled blast furnaces, mechanized cotton mills and chemical factories were wonders of the Industrial Age to the curious Georgian traveler.

At first sight, Blenheim might also fit the sufficiently known category. But viewed through the eyes of an early 19th-century visitor a different image emerges. The Bennets are gentry, but not the high-born, upper-crust who would have been welcomed as guests. Lizzie arrived, like we do today, as a tourist. Walking up those famous golden-stone steps, the palace’s sheer splendor, massive columns and very finest of fine art are spectacular, but also somehow intimidating.

There is no evidence Austen was inspired to base Mr. Darcy’s terrifying relative Lady Catherine de Bourgh’s “Rosings” on Blenheim, but the magnificence of that banqueting table and the opulence of the ceiling above it is enough to make even Austen heroines take a deep breath.

Some of Blenheim’s delightful moments are to be found in its more intimate spaces. The exquisitely-painted Indian Room’s glass doors look across the formal gardens, conjuring lazy afternoon teas for visiting ladies. The murals arrived in 1820, so Lizzie would have just missed them; the room was called the Stone Gallery in her day. Nibbling a finger sandwich and sipping a cup of Assam at one of their afternoon teas, though, it’s easy to dream Jane Austen might have tasted something similar.

The terraced gardens of Blenheim Palace gleam much as they did in Jane Austen’s day.

The cable car operator called the day “murk-some.” The day I visited, Matlock’s Heights of Abraham (named for the scene of Wolfe’s Battle of Quebec) were so shrouded in wet, white fog there was no view Whatsoever. Inclemency notwithstanding, by the early 19th century Matlock’s views were a major draw. The Great Rutland Cavern was opened to the public in 1810, three years before Pride and Prejudice was published. Doughty travelers were lowered in buckets into what was a working lead mine, frocks, bonnets and all for a penny. It was another penny if you wanted to go up again, though this vital information was not advertised on the way down. There’s a walk-in entrance now.

On a rare sunny day, Sandra overlooks the prospect of Dovedale and the Peaks.

As every visitor to Derbyshire knows, the weather changes by the hour. The next day the sun was shining, the rivers sparkling and the blue skies above Dovedale warm and inviting. It’s easy to see why Elizabeth and her relatives fell in love with the soft, rolling hills tumbling into the two-mile valley embracing the river Dove. The mellow dry-stone walls, spring greenery, and woolly white lambs are enchanting.

Many scholars argue that Bakewell, four miles from Chatsworth House, was the inspiration for the village of Lambton where Elizabeth stays before her visit to Pemberley. The town remains compact, quaint and, apart from the constant traffic, not unlike Jane Austen would have known it, with tiny courtyards, meandering alleys, and several bakeries, each claiming to be the one and only home of the original Bakewell pudding. Elizabeth wouldn’t have tasted the delights of the delicate almond pastry invented in 1820, but I was entranced to find a ribbon shop in a pink, half-timbered courtyard that would have kept Lizzie’s sisters Kitty and Lydia in enough lace to drive Mr. Bennet to distraction.

“I believe I must date it from my first seeing his beautiful grounds at Pemberley,” quips Elizabeth when her sister asks when she first loved Mr. Darcy. And it’s easy to imagine how she might have felt when you first glimpse Chatsworth House in all its magnificence. It’s widely agreed Austen had Chatsworth in mind when inventing Pemberley: “neither gaudy nor uselessly fine.” Like Elizabeth, we can tour parts of the house “open to a general inspection,” pausing, as she did, “to enjoy its prospect.”

“And of this place,” thought she, “I might have been mistress.”

Finally, the peaks. Bleak on the sunniest day, their stark beauty is captivating and awesome in equal measures. In a moment of flippancy, I suggested to our esteemed editor that I emulate Lizzie’s famous BBC shot, digging out the clothes I wore for the Regency Ball a few years ago to find out what it might have been like to visit a natural wonder the way our ancestors might have done. Of course, he called my bluff.

Elizabeth Bennet would have worn thin, kid-leather boots, flimsy muslin dresses and short cotton spencer and fine wool shawl to clamber over the millennia-smoothed rocks piled together by the melting of ice ages. I attempted similar. If I learned anything from the experience—wind, cold, bursts of rain, sudden rays of sun—it was to admire the hardiness of our 19th-century forebears determined to enjoy the sights of England in spite of their clothes.

But gosh, the Derbyshire Peaks are inspiring, no matter what period you are visiting them in, and however you might be dressed.

Catch the details

PEAK DISTRICT: For information on the Peak District visit www.visitpeakdistrict.com

BLENHEIM PALACE: Afternoon Tea is served each day from 1 p.m. to 5 p.m., £19.95. Booking is essential.www.blenheimpalace.com.

CHATSWORTH HOUSE: Visit www.chatsworth.org.

* Originally published in 2015.

Comments