Roman Fortifications in the Museum Gardens of York.

Eboracum to Jorvik to York - Where the streets are called gates, the gates are called bars and the bars are called pubs.

From the days of the Romans, York has been the political and ecclesiastical capital of the North. Packed into its 14th-century city walls, York contains a microcosm of English history and architecture. If any place outside of London deserves to be put on a list of must-see places in England, York it is. I have been returning to York for 30 years, and recently returned again to see whether my convictions held up.

They did. York never loses its magic.

Read more

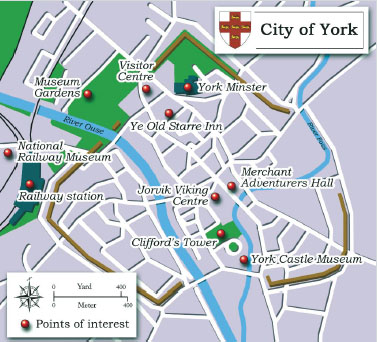

York is an easy two-hour train ride from London, with hourly trains from King’s Cross. From the arrival point at York Railway Station, the city quickly hints at its treasures. One of Victorian England’s great buildings itself, York Station was the largest train station in the world when it was built in the 1870s. You emerge from the station to face York’s crenelated 14th-century city walls.

York’s largely pedestrianized city center is a cornucopia of crooked alleys, broad tree-lined squares, narrow streets and surprising byways, some dating back to the 1300s. Now as then, York is a posh shopping mecca. High Street marques like Marks & Spencer receive plenty of competition from a dizzying array of specialty shops, boutiques, tearooms, and eateries. A street market enlivens Newgate daily, while talented buskers amuse the pulsing crowds. On The Shambles, a cobbled lane named for medieval butchers’ shops, I spotted in one shop window the appropriate slogan Veni, Vedi, Visa: “I came, I saw; I did a little shopping.”

Like many ancient towns in Britain, York owes its origins to the Romans. They called it Eboracum and used the river port as both an administrative capital of this farthest outpost of the Roman Empire and as a military staging area for administering Hadrian’s Wall and governing unruly northern tribes. A bit of the Roman wall still stands on St. Leonard’s Place near the City Art Gallery. The undercroft of York Minster reveals Roman foundations as well.

Like so many Roman urban areas, Eboracum drifted into decline after the Roman departure in the 4th century. Its location on the navigable River Ouse, however, kept the town vital as a trading base. In the 9th century, alas, the Vikings discovered its prime location and relative wealth. During the Viking occupation of the 900s, Eboracum became Jorvik, a principal Viking port and control and command center.

The Viking Danes left a sure mark on the city. It was their language that called streets gaedes or gates, and their word for gates of the walled city, bar. At the Jorvik Viking Centre off Coppergate, you can ride in a time tunnel back to a quay of the Ouse in the Jorvik of 989. It is a remarkable recreation of Jorvik’s 10th-century daily life, smells and all. Then, ride through the actual archaeological laboratory of the dig on which Jorvik was recreated. It’s a fascinating multisensory story.

After the Norman arrival in the 11th century, William the Conqueror built a castle at York and the city officially entered the Middle Ages. What remains of the castle today is the keep, Cliffords Tower, rebuilt in the 13th century and now in the care of English Heritage. If you climb the mound and the ramparts of the tower, you’ll find remarkable views of the city in all directions. You are looking at the teeming medieval city, within the most completely intact medieval city walls in the country.

Down at street level again, York has all the accouterments of a fashionable modern town. But its plethora of medieval buildings and unaltered, narrow streets and alleys give York a more pervasive sense of medieval English town life than anywhere else I know. I stopped at Café Nero for a cappuccino.

York has many attractions, but three top the list. Most striking—and most visible from anywhere in the city—is majestic York Minster. The largest Gothic cathedral in northern Europe, the Minster was completed in 1472 after 250 years of craftsmen’s work.

GREGORY PROCH

The Minster is the seat of the northern archdiocese of York and “home” to the archbishop, now the popular Rt. Rev. Dr. John Sentamu. The magnificent Great East Window, created from 1404 to 1408 and the size of a tennis court, is the largest stretch of medieval stained glass in the world. A full-size print of the window currently hangs in front of it while the 15th-century panes are being restored in a major two-year touching-up project.

What I love best about York Minster, especially compared to many of England’s great medieval cathedrals, is its lightness. The soaring tracery and colorful ceiling bosses stand out with light from the high clerestory windows and the pale building stone.

Outside the city walls near York Station sits the National Railway Museum. It is simply the largest railway museum in the world, and it offers free admission. The huge exhibition halls house virtually everything imaginable for train buffs’ delight. From Stephenson’s 1829 Rocket to a car from the Japanese “bullet train,” if it rolled on rails, it is represented here.

The museum exhibits early passenger coaches, which were really just stagecoach bodies mounted on a rail undercarriage, and The Mallard, which holds the world’s record as the fastest steam locomotive ever (125 mph). A featured exhibit highlights The Flying Scotsman, the famous express service between London and Edinburgh begun in 1862. The daily 10 a.m. express from London Kings Cross to Edinburgh is still officially The Flying Scotsman. The journey took 101½ hours in 1862; today it can be done in just over four.

Among the most popular exhibits is the collection of “Royal trains,” which have carried the country’s monarchs all over the island. The plush carriages of Queen Victoria and King Edward VII are just fun to see.

As if one world-class museum were not enough for York, across the river, behind Clifford’s Tower, is the Castle Museum. One of the greatest folk museums anywhere, the Castle is a veritable warren of eclectic galleries depicting York and Yorkshire’s populist past. Following the natural trail of galleries leads first to period rooms, furnished as they would be in successive periods of history. A Moorland Cottage of the 1850s, for instance, represents the family living area of a rural cottage of the northeast of Yorkshire. We also see the living room of a typical home in the 1950s—celebrating Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation in 1953.

Harry Humberstone guards the delectables at Little Betty’s on Stonegate. Dana Huntley

After galleries displaying domestic appliances through the decades, we emerge onto Kirkgate, a complete Victorian High Street of about the 1870s.

Caroline Richardson, in costume as a clerk in a shabby neighborhood shop, chatted with me about the retail realities for the Victorian masses. “There would have been rats and vermin,” she advised. “In posh shops, these canisters would be full of tea and things like that. Here we sell tea dust. Here, people get things like rice and tapioca, all your dry goods.” Richardson comes into the museum on call to play her role. Meeting the people, especially the schoolchildren who visit Kirkgate, is “great, just great,” she enthuses.

But we’ve got to keep going. There is still a greatly touted Museum of Costume, galleries on the Civil War and more. The newest exhibition gallery in the Castle is devoted to the Sixties. It does seem so dated now to look back at the fashion, music, home décor, pop art and themes of those colorful, hurly-burly years.

The trail leads unblinkingly from the Sixties to the old debtor's prison, where the old cells are now craftsmen’s workshops: the gunsmith, the cobbler, the brushmaker and such. Besides debtors, the prison held felons, and, in 1746, Jacobite captives after the Battle of Culloden. A lot of them were hanged here. Chartists and Luddites were imprisoned here as well. Somehow we end up in the cell of the famous highwayman Dick Turpin. They hanged him, too. After any one of those Big Three Visits, it’s apt to be time for lunch. There are options everywhere in York. I ate a late lunch one day at The Punch Bowl in Stonegate, widely heralded as having the best pies in York. From 10 different pies and a seasonal specialty on the chalkboard menu, I chose the steak and Guinness pie. It arrived steaming on a huge trencher with mash and steamed vegetables. Chicken, bacon and leek; game pie; chicken, red wine and baby onions all sounded great. The Punch Bowl has been here 400 years, so it has had time to get food right. And it did.

But the place to have lunch in York—or morning coffee, afternoon tea or a light supper—is Bettys on Davygate. Bettys has been a Yorkshire institution since its first shop in Harrogate opened in 1919. Both a bakery and tearoom, Bettys serves up classic English teas and lunches with its own specialties (like Yorkshire rarebit) and imaginative sweet concoctions. A marzipan-robed cream cake looking just like a fresh pear will accompany that rarebit nicely, thank you. Be forewarned, however, there is always a queue out the door from late morning until dark to get a seat at Bettys.

Whether you are following a purposeful plan to “see” York or just randomly exploring the city’s streets, it is impossible to turn any corner or wander any “gate” of the old city without stumbling upon a museum, monument or attraction of some sort.

The Merchant Adventurers Hall on Piccadilly is one place well worth seeking out. It is the finest surviving medieval guildhall in England, built between 1357 and 1361, with an impressive open oak-beamed roof. Originally a religious guild, the Merchant Adventurers Hall includes the only medieval guild chapel surviving in Britain. The undercroft, or ground floor, was supported as a hospital or hospice from 1373 until 1900. The “inmates” were infirm men and women, cared for by chaplains.

Most remarkably, the building has remained in the hands of the Merchant Adventurers from the time it was first commissioned.

‘IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TOTURN ANY CORNER WITHOUT STUMBLING ON A MUSEUM OR MONUMENT OF SOME SORT’

One of the greatest folk museums in the world, the Castle Museum is a warren of eclectic galleries depicting York’s populist past . Dana Huntley

Yes, the guild still exists. Though it no longer is an active trading organization, the civic group of businessmen and women promotes commerce in York and a greater understanding of enterprise in society. They also take care of the building.

Many of York’s ancient churches are open to visitors, and each of them has a story to tell. St. Martin-le-Grand on Coney Street, dating back before the Norman Conquest and once one of York’s most splendid churches, was gutted by German incendiary bombs in April 1942 and slumbered in ruins until 1968. It was restored and rehallowed as a Chapel of Reconciliation between nations and between peoples. The beautiful pipe organ was donated by the German government and the German Evangelical Church.

Constructed in 1535-36, St. Michael-le-Belfry on Low Petergate is the only pre-Reformation church in York built in one go. The infamous Guy Fawkes was baptized here; he was born across the street. Today, the active parish has 800 regular congregants.

All this footwork, however, is bound to create a powerful thirst. Long ago I made my York “local” Ye Old Starre Inn on Stonegate. York’s oldest pub, the Starre was licensed in 1644, though they reckon it might have been a pub for 200 years before that. Cromwell’s troops took over the inn for use as a hospital during the Civil War, ticking off the Royalist landlord. I am happy to report the real ale is as good as ever.

Another option for giving the feet a rest is taking a boat ride. You can get an entirely different perspective on the ancient city from the River Ouse. York Boats offers 45-minute cruises with live commentary on well-furnished riverboats. Grab a drink from the bar and let the city and country sail by. You can catch the boat at either Lendal Bridge or Kings Staith Landing.

At some point, every visitor ought to walk at least a stretch of York’s 14th-century city walls.

My favorite segment runs from Bootham Bar, near the West front of York Minster, in back of the cathedral close and townhouse gardens to Monk’s Bar. The gatehouse at Monk’s Bar houses a modest but informative museum of King Richard III. He may have been a bad ’un, but he was Yorkshire’s own. Visitors are invited to vote on whether the hapless king deserves his rather onerous reputation.

Always a good place to start a visit, York’s Tourist Information Centre lies on St. Leonard’s Place, conveniently between the railway station and the Minster. Across the street are the City Art Gallery, the grounds and ruins of St. Mary’s Abbey and Yorkshire Museum. Next door is the Theatre Royal. It is a beautiful small theater, with a full program of top quality productions throughout the year.

I spoke to friendly Rebecca, one of more than 40 staff members of York’s tourist operation, at the information center. She reported that the city receives 4 million visitors a year, and reminded me that York is the most haunted city in Britain.

Indeed, after dark, York’s ghosts—or at least the ghost hunters—take over. Several competing companies now offer nightly ghost tours, including World Famous Original Ghost Walk, which claims to have been “Disturbing people since 1973.”

I expect the specters have a sense of humor.

Kebab carts also appear on the street after dark, replacing the daytime sausage wagons and ice cream carts along Parliament Street. They serve up kebabs to folks emerging from the pubs until well after midnight.

From Thai to Tapas, Turkish to TexMex, every kind of ethnic dining is available in York. Always on the lookout for a good curry, I sought out Bombay Spice on Goodramgate one evening. It finely proffers all the classics, from kormas to jalfrezis. On another evening, I ate at Russells of Coppergate, something of a York institution. Russells’ traditional carvery serves up joints of beef, pork, lamb, gammon and turkey for the slicing, with all the traditional accompaniments, vegetables, and salads.

Whatever the adventures of the day, I am apt to end up back at Ye Olde Starre Inn for a pint and some good conversation. You can meet visitors from all over the world in York’s pubs, and many pubs have full programs of live music in the evening. York’s own people, though, are easy to talk to, full of a native Yorkshire friendliness and good nature. It’s a fine way to finish the day in one of the world’s most exciting small cities.

Planning for York

▪ National Railway Museum, Leeman Rd. Open daily from 10 a.m.; Admission free www.nrm.org.uk

▪ York Castle Museum, Castle Area Open daily from 9:30 a.m.; Admission £7.50 www.yorkcastlemuseum.org.uk

▪ York Minster, High Petergate Open daily from 9 a.m.; Admission £5.50 www.yorkminster.org

▪ Jorvik Viking Centre; Coppergate Open daily from 10 a.m., Admission £8.50 www.jorvik-viking-centre.co.uk

▪ The York Pass

The York Pass is a great, cost-saving way to see the city. Purchased for a varying number of days, the York Pass offers entrances to more than 30 attractions in York and the surrounding area. www.yorkpass.com

▪ Visiting York The excellent, official tourism Web site for York includes comprehensive information on accommodation, shopping, current events, and York’s many visitor attractions. www.visityork.org

* Originally published in May 2009.

Comments