DurhamGetty images

What makes Durham, Durham?

Stand on Palace Green, the grassy square in Durham’s historic peninsula, and you confront an embarrassment of riches. Which way to turn first? To the south is Durham Cathedral, rising up in majesty toward the heavens. To the north is Durham Castle, now home to part of the University of Durham, an imposing stone keep converted to academic use.

These two buildings, separated by yards, are the basis of a World Heritage Site and helped create and preserve this distinctive historic city, one that has attracted visitors for centuries. But what makes Durham, Durham? The answer is to be found right here in the heart of the old city, in the two magnificent structures on either side of you.

The city won’t explore itself, so don’t stop and stare for too long. Start by heading south through the wooden doors of the cathedral. Hopefully, you won’t need to rap the sanctuary knocker, which grants those who have committed “great offenses” 37 days of sanctuary within the cathedral boundaries.

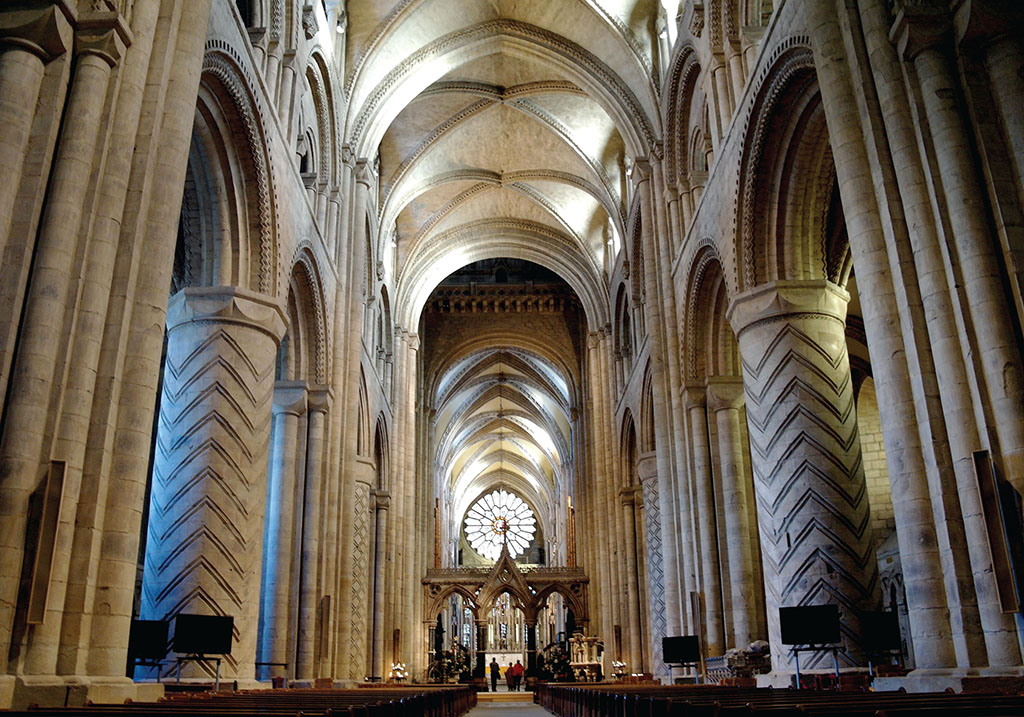

Starting in 1093, Durham Cathedral was built over the course of four decades to house the body of St. Cuthbert. Much of its original Norman architecture remains. This was the first church to use ribbed vaults with pointed arches to support a high ceiling, and it is the world’s oldest surviving large stone-vaulted ceiling. The stonework soars high into the air, reaching ever-closer to the God that the original monks wanted to praise.

SCOTT REEVES

“The nave is my favorite place in terms of architecture and aesthetics,” confides Michael Sandgrove, the cathedral dean. “I sit there and marvel at the incredibly finely proportioned nature of this building. The drum piers, the vaults, the aisles, the arcades: everything is in perfect proportion here, and you don’t often get that with Romanesque architecture. It is a Goldilocks building, it’s just right. Not too high, too low, too wide or too narrow.”

The dean is not alone in his opinion. A poll by The Guardian voted Durham Cathedral as Britain’s favorite building, while architectural historian Dan Cruikshank picked it as one of his four choices for Britain’s best building.

Yet all of this would not have existed if not for the life of Cuthbert, a Dark Ages holy man. Cuthbert was a hermit who lived on the Farne Islands, close to Lindisfarne. After his death, miracles associated with Cuthbert led to his shrine at Lindisfarne becoming the main site of pilgrimage in Britain. Viking attacks had forced the monks to transport Cuthbert’s relics around the northeast until, 200 years later, he was laid to rest at Durham after a milkmaid led the monks to a loop of the River Wear that offered a safe sanctuary.

At the east end of the Cathedral, behind the altar, is the shrine to St. Cuthbert. “You can’t go in and out of this building without being aware of the history of St. Cuthbert,” the dean says. “I go into his shrine very often. It reminds me that the emotional and spiritual heart of the cathedral is Cuthbert’s shrine.”

The gilded green marble slab would once have been surrounded by lavish jewels and expensive embroideries, but they were all disposed of during the Reformation. St. Cuthbert’s body remained, however, after the King’s commissioners were spooked by how unnaturally well-preserved it remained.

The shrine remains a place of pilgrimage. More than 600,000 people pass through the doors each year, many to attend one of the 1,700 services. Tourists who flock to the cathedral join the worshippers in a quiet, reverential atmosphere.

“We don’t call them tourists. They are visitors,” the dean interjects, “and it is a very big management task to give our visitors the best possible experience. We want to help them appreciate what it is they are coming into, that it is still a place of worship. Some of them even ask, ‘do you still hold services here?’”

The cathedral caters to its visitors in a number of ways. All are greeted as they enter by volunteer stewards who are on hand to answer questions and lead guided tours. Yet they are a subtle bunch, happy to slip into the background, allowing the cathedral to retain an atmosphere of reverence and devotion.

Durham has not fallen into the modern trend of placing a desk clerk by the door to demand an entry fee, which can feel more like entering a theme park rather than a medieval cathedral. There are still many ways to contribute to the upkeep of the building. Donations are welcome, and visitors can also pay to climb the tower, explore the exhibitions in the cloisters or enjoy refreshment in the Undercroft Restaurant.

SCOTT REEVES

Be careful not to stay too long, however, because Durham Castle, the other half of the World Heritage Site, patiently awaits your attention. Construction of the castle began before the cathedral, in 1072.

Within three years it came under the control of the church and was the principal residence of Durham’s Prince-Bishops. For 750 years, the Prince-Bishops oversaw the protection of northern England from the troublesome Danes and Scots, and the stone walls deterred attacks against Durham.

In the 1830s, the Bishop of Durham was stripped of his temporal powers and moved a few miles down the road to Auckland Castle. That left the Castle free to house the newly created University of Durham, an institution that owes its origins to two clerical patrons, Archdeacon Charles Thorp and Bishop William van Mildert.

Durham became home to the third-oldest university in England after Oxford and Cambridge. Students moved in to Durham Castle (officially named University College, often just called “Castle” by its students) and began to transform the old building to suit their needs.

The juxtaposition of castle, bishop’s residence and university can be seen on one of the daily tours. Each is led by a student volunteer, one of whom is Kaja Marczewska, a Castle student studying for a Ph.D. in English Literature. Her knowledge and enthusiasm would put professional tour guides to shame.

“We want to show off where we live and study,” Marczewska explains. “Such magnificent surroundings create a sense of pride; it gives us an identity. The undergraduates have a different attitude to the place compared to other universities. It draws people in, gets them involved.”

Three meals a day are served to the student community in the Great Hall. Though slightly shortened nowadays, features such as the trumpeters’ gallery make it easy to picture this grand hall being the center of the medieval castle. Rather than college tutors sitting at the top table, it would have been reserved for the Prince-Bishop and his entourage. Elements of older tradition remain. Formal dinners are held twice a week, during which careless students can be fined £60 if they leave their seat before the college master has finished his meal. Seating is hierarchical, with tables designated for tutors, postgraduates and undergraduates. “It might sound old-fashioned, but it adds to the experience of studying here,” Marczewska says. “Most students like the quirky rules.”

Such segregation is seen elsewhere, too. Only postgraduates and tutors (and guided tours) use the Black Staircase, which leads from the Great Hall to the Tunstall Gallery. The stairs lean alarmingly. Initially designed as a flying staircase with no pillars for support, the builders soon realized their mistake and were forced to add wooden posts to hold it up. Their repairs did the job, and the staircase still stands more than 300 years later.

Up another level is the student accommodation in the Norman Gallery, but this is off limits to tours. “The rooms are beautiful, but access to bathrooms is not great,” Marczewska confides. More students are housed in the old keep, with an enviable view across Palace Green toward the cathedral.

At the end of the Tunstall Gallery is the Tunstall Chapel. Built during the first days of the Reformation, like all areas of the castle, it is still used by modern students. Less used is the Norman chapel underneath. Historians are still arguing about whether this was the original chapel, or an undercroft or crypt that survived when the original place of worship was superseded by the Tunstall Chapel. Whatever the case, it is an atmospheric spot still used for church services, theatrical performances and concerts.

The new university did not just take over the old castle. Over the next few years, the university’s reach spread into buildings which were constructed during the heyday of Durham’s Prince-Bishops. The second university college, Hatfield College, partly occupies a 17th-century inn, while St. Chad’s College, St. John’s College and St. Cuthbert’s Society are housed in decadent Georgian townhouses. An amble along North Bailey and South Bailey, streets whose names indicate that this whole area was once part of the castle, takes in each of these places of learning.

Discovering Durham

Durham is a straight-line trip from London. By road, take the M1 north and keep following as it turns into the A1(M) at Leeds. Alternatively, take the direct train from King’s Cross (eastcoast.co.uk).

There are plenty of hotels to stay in around the city, but a visitor looking for the authentic World Heritage Site experience should consider staying in one of the state rooms at Durham Castle (dur.ac.uk/event.durham/tourism). Other colleges also offer bed and breakfast, especially during university vacations.

Information about visiting Durham Cathedral and Durham Castle can be found on their websites (durhamcathedral.co.uk and dur.ac.uk). Opening times and tours may vary depending on the time of year and sundry special events, so be sure to check in advance. Both are also featured on the dedicated Durham World Heritage Site website (durhamworldheritagesite.com).

SCOTT REEVES

The dean of the Cathedral sums it up well. “The university is a child of the cathedral, and there has always been a close relationship between the two. We are very close partners.”

Comments