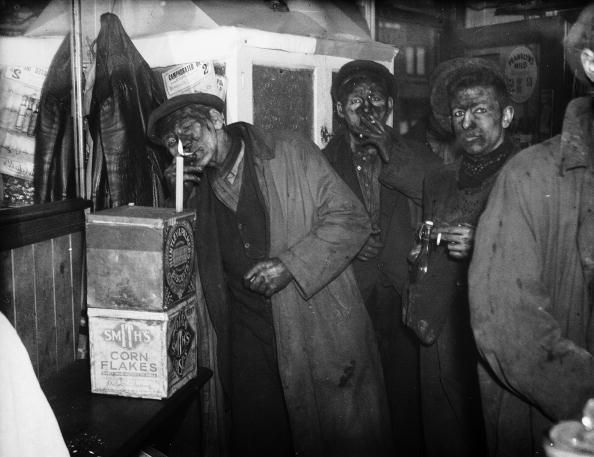

Taking a moment: Two Welsh miners pause for cigarette.Getty

The scars left behind by the collieries of Wales’ Rhondda Valley are beginning to heal, but some things never change.

Scarcely an hour's drive west of the pristine villages, prosperous cottage gardens, and sylvan landscapes of the Cotswolds lies the southern Welsh county of mid-Glamorgan. Throngs of touring coaches, camera-wielding photojournalists, and well-heeled tourists don’t come here. These are the valleys of the Rhondda.

In the Valleys

Fanning out above the Welsh capital of Cardiff, these valleys are the coalfields of South Wales, narrow glens snaking their way south to north, from the Bristol Channel coast toward the Brecon Beacons. Every few miles up and down the hills lie the skeletal remains of a pit head, rusting silently, majestic.

Though in popular parlance the name Rhondda has become synonymous with the mining district, the Rhondda itself is a dual-pronged valley rising north of Pontypridd. The “Little Rhondda” threads its way from Trehafod north to Maerdy, where the road runs over the hills to Aberdare. The “Great Rhondda” branches west to Treorchy and Treherdert, then winds north to meet the Head of the Valleys Road at Hirwaun. The people here just call them “The Valleys.”

6

6

The blackened faces of the hardworking Welsh coal miners.

The blackened faces of the hardworking Welsh coal miners.

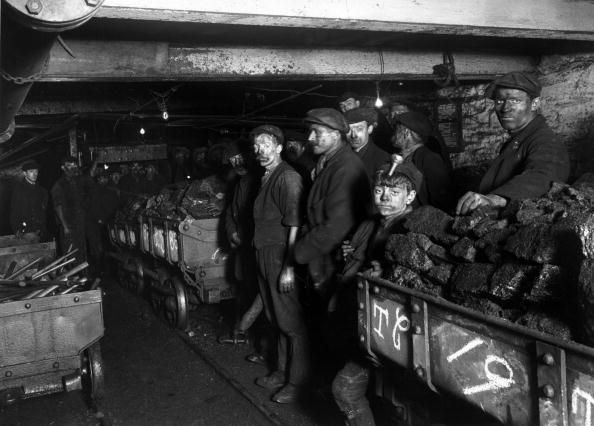

For more than a century, high quality, smokeless coal was extracted from the earth here. Collieries dotted the valleys, and tens of thousands of men made their livelihood cutting coal from the rich seams that ran from several feet to more than a quarter-mile under the surface. This huge economic engine built the industrial port cities of Cardiff and Newport and fueled the British navy from the later years of Victoria almost until the Second World War. Today the coal mines are silent, unprofitable in the modern economy. Though the pits have closed, however, the people remain in populous, serpentine towns lining the vales.

Read more

Life in the valleys has always been hard. During the winter, a collier never saw the sun except on Sunday, going into the pits before daybreak and emerging again after dark. Boys followed their fathers down in their early teens. With little cash and no modern conveniences, women made home and hearth for large families in two-room-up, two-room-down stone row-houses without garden or lawn. The mines yielded a death, on average, every six hours, and a serious injury every 12 minutes.

Mining communities

In Senghynydd at the head of the Aber Valley, local historian Basil Philips recounts the story of the deep pit explosion of 1913, when 434 men and boys in this village of less than 5,000 met their deaths in the greatest colliery disaster in British history. His own father was in the mine that day.

The Valleys

Philips tells how the mining communities were built. As a pit was sunk, it drew men off the land, swapping the bleak agrarian life in the hardscrabble Welsh hills for the steady cash wages of the mine. As hard as life might have been, it was an enviable step up from subsistence farming.

“A man looked for four things coming to work in the pits,” Philips recalls. “A roof over his family’s head, a chapel, a men’s choir, and a rugby team.” While life has inevitably changed here in South Wales, the legacy is easy to see. The terraced houses are still home, though it is hard to find a block where several of them are not adorned with “For Sale” signs.

The dissenting chapels, Baptist, Methodist, Congregational, and Presbyterian, certainly punctuated every neighborhood. Today, most of the chapels are as silent as the mines. Many sit derelict or converted to other uses in the secularism of late-20th-century Britain. Fewer than three percent of the Welsh people now attend. This remnant keeps alive an important part of the valley’s history, a dissenting gospel, and many of the grand Welsh hymns for which the region is renowned.

Welsh miners

Choir culture

The justly acclaimed male voice choirs of Wales remain. In fact, Senghenydd itself is home to one of the best, the Aber Valley Male Voice Choir. Every valley and village has its own choir. Their music continues to be one of the great defining cultural institutions of Wales; opera choruses and Welsh hymns, folk songs, and show music. As well as maintaining active concert schedules, most of the men’s choirs are happy to welcome visitors to their rehearsals.

As to rugby, it is the national sport. Girls and boys pick up the game early in instructional leagues, and the great players are national folk heroes. Wales proudly hosted the quadrennial Rugby World Cup in 1999. In the sprawling valley towns, signs of economic depression and need may abound next to an immaculately maintained, flood-lit rugby pitch.

Life in the valleys is still hard. The pit closures through the ’80s brought massive unemployment to an already depressed region. Vast amounts of investment capital poured into the region from elsewhere in Britain, the European Community, the United States, and Japan. Though new factories have risen along with the Head of the Valleys Road and across the jagged southern end, unemployment remains very high in some places.

Despite this story of hard industrial life and general economic depression, the people of the valleys are warm, good-humoured, resilient, and hospitable. Visitors fortunate enough to discover the valleys find an open welcome, a unique culture, and a great deal of interest.

As Wales is a bilingual principality, of course, that friendly greeting could come in either English or Welsh. The only living Celtic language, and the oldest living European language, Welsh is visible on highway signs, in shop windows, and in print. Many schoolchildren in the Rhondda area attend schools where Welsh is the language of instruction.

Welsh choir at a rugby match

Gateway to the Valleys

The market town of Pontypridd lies in the centre of the region and calls itself “Gateway to the Valleys.” The Historical Centre in the heart of Pontypridd exhibits the social and cultural history of the town and doubles as the Tourist Information Centre. It is located in a former chapel. The magnificent pipe organ, still used for recitals, is the one feature that remains of the building’s chapel years. It was once the instrument of John Hughes, who composed the classic hymn Cym Rhondda, still sung throughout the world as Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah.

Just a few miles up the road at Trehafod, the Lewis Merthyr Colliery has found new life as the Rhondda Heritage Park. Here among the rusting relics of busier days, the unique industrial heritage and way of life is kept alive. In multimedia and reconstructions of village life, the Heritage Park tells the history of the Rhondda. Former colliers, who worked these pits for years, lead visitors underground to experience working life in the mine during the 1950s.

Half a dozen miles to the south, the prosperous market town of Caerphilly had already been around for centuries. It sprang up in the shadow of Caerphilly Castle, the largest castle in Wales. Built in the 13th century by the Norman lord “Red Gilbert” de Clare, the fortress stands on three artificial islands in a 30-acre lake. Its usefulness as a fortification is long past, but the castle still dominates the town. Local folks take the mammoth castle and its unique display of medieval siege engines quite for granted. Their greater interest is fishing in the lake.

Just across the street, the Caerphilly Visitor Centre not only provides tourist information, but exhibits the local history and offers Welsh crafts, gifts, and a ready source for the famous white Caerphilly cheese.

The hills are greener now around here than they were when Richard Llewellyn described them in his famous, heart-warming novel of the coalfields, How Green Was My Valley. They are greener than they were a generation ago. The mountains of coal slag are now swaddled with vegetation. Stands of farmed evergreens run along many of the ridges. Still, there is no pretending that the valleys are a beautiful place, or that they will ever rival the Yorkshire Dales or the Cotswolds for the devotion of visitors, infusion of tourist spending, and creeping gentrification. Unfortunately, those seeking the pastoral Britain of popular imagination will have to look elsewhere.

The Valleys

The power and attraction of the Valleys lie in the warmth of her people and in an identity forged over centuries: in her homes and chapels, on the playing fields, and in the strong magical voices of her men’s choirs raised in Welsh anthems like Calon Lan:

Oh pure heart, so true and tender,

Fairer than the lilies white,

The pure heart alone can render

Songs of joy both day and night.

That song of the heart alone makes the valleys worth the visit.

Dana Huntley is the president of Lord Addison Travel and a frequent contributor to British Heritage.

Read more

* Originally published in Sept 2004.

Comments