Virginia’s dynamic governor, Sir William Berkeley, spells out his clear vision to the colonial assembly

As England lurched toward civil war and the puritan commonwealth, the colony of Virginia became a refuge for royalists loyal to the Stuart monarchy. Through the middle decades of the 17th century, aristocrats and adventurers sought a new life in a new world.

By 1649 Sir William Berkeley’s home, Green Spring was finished, and he was entertaining on a grand scale. Situated on a high natural terrace above the James River, Green Spring was the first English stately mansion built in the colonies. The plantation of Virginia’s colonial governor was one of many such English manor houses established across Virginia and the southern colonies in the late 17th and 18th centuries. They were built by the families of aristocratic Cavaliers who had followed the siren-call of Sir William across the Atlantic to the colony of Virginia.

If England was a difficult place for Puritans and Dissenters in the 1620s and ’30s, by the early 1640s the tide had turned considerably. King Charles I had tried desperately to preserve the “royal prerogative” and hold on to the power of the monarchy as his father, James I, had taught him. Increasingly, however, the elected House of Commons of his Parliament represented Puritan interests religiously, socially, and economically. Crown and Commons became locked in a battle for control of England and its constitution.

Read more

When civil war seemed inevitable in the early 1640s, London itself was a Parliamentarian stronghold, like the counties of East Anglia and the East Midlands. The court of King Charles removed to Oxford, where many noble families flocked to his standard. One such family was the Berkeleys. Having had their seat at Berkeley Castle since the 1200s, the Berkeleys were among the richest and strongest families in England. They owned castles, manors, and land all over the western counties of Gloucestershire, Wiltshire, Somerset, and Devon. In fact, it is said that at one time the Earl of Berkeley could ride from his castle at Farleigh Hungerford, near Bath, to Berkeley Square in Westminster without leaving his own land.

Sir William Berkeley came from a cadet branch of the family. His father, Sir Maurice, was of the Somerset Berkeley, and William grew up in their home at Bruton Abbey. After being schooled at Oxford and taking the Grand Tour, William secured an appointment at court and established something of a minor reputation writing plays. He was knighted for serving the king in the Bishops’ Wars of 1639-40, but saw also that the king’s policies were edging the country toward civil war. Using the influence of his relations and court connections, Sir William purchased the office of governor of Virginia and, commissioned by King Charles in August 1641, set sail for Jamestown to seek his fortune.

Berkeley wasted no time putting his personal imprint on his new colony. When he landed in Jamestown, Virginia was a small and marginal community of only 8,000 English settlers. Berkeley immediately became one the colony’s planting elite, arriving with easy access to land and a sizable contingent of servants and laborers. By 1643 Berkeley had acquired the property of Green Spring, some three miles upriver from Jamestown. In addition to building the first Anglo-American stately mansion there, Berkeley determined to make his plantation a showplace of the agricultural industry and economic diversity. Within five years, he was exporting rice, liquor, silk, fruit, potash, and flax, as well as the principal Virginia commodity—tobacco. In the long run, Berkeley’s attempts to diversify Virginia’s tobacco-bound agrarian economy failed. In the short run, however, Sir William became exceedingly prosperous and influential. It was he, indeed, who almost single-handedly recruited the colonists and formulated the society and culture of colonial Virginia.

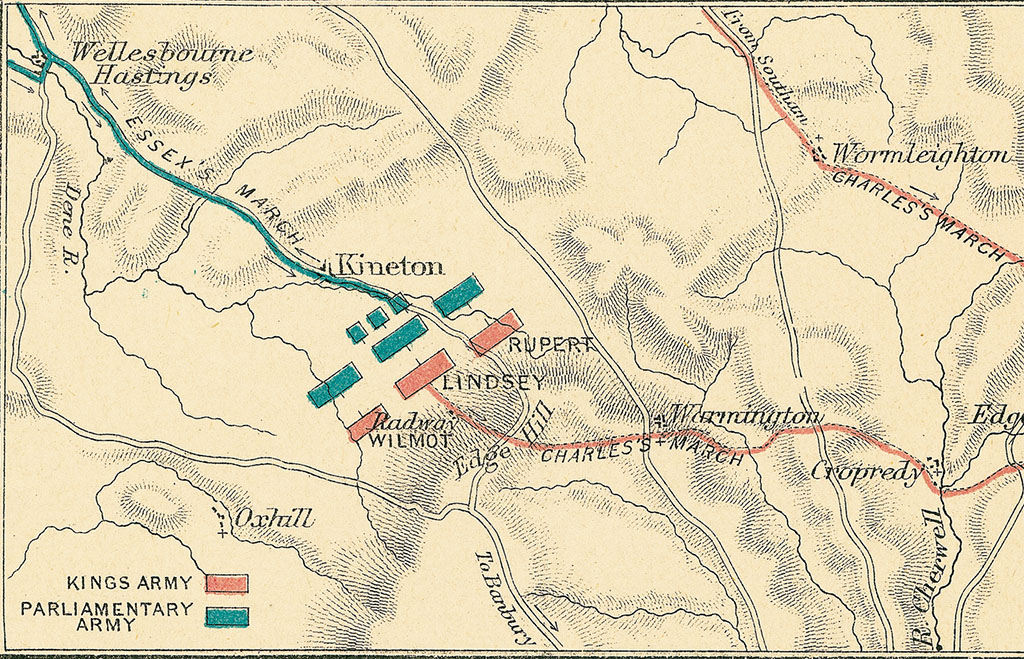

Back in the mother country, shortly after Sir William landed in Jamestown, Parliament and the Crown did exchange mortal blows. In the autumn of 1642, the respective armies of Royalists and Parliamentarians came to serious engagement at the Battle of Edgehill near Banbury. The country would be in open warfare for the next 10 years. The cause of Parliament was the Puritan manifesto of representative government and godly order. The king was supported by the High Church and by the nobility and landed aristocracy whose vested interests, influence and wealth rested with the Crown.

Though the Battle of Edgehill was a tactical draw, the withdrawal of a weakened Parliamentarian force gave the advantage to the king.

Being a Royalist and a conforming Anglican were synonymous for those followers of the Stuart monarchy and King Charles I. Just as Puritan partisans became known as Roundheads, among other names, so Royalists became known as Cavaliers. And cavalier they were, too. The young bucks of Charles’ hereditary officers corps and the highborn camp followers of the king’s cause had a swagger and moral confidence about themselves and their world. They were men who had grown up with power and wealth, accustomed to receiving deference from their tenant farmers and the rest of the lower class folk who comprised 90 percent of society.

No one of his days was more the Cavalier than Sir William Berkeley. Sir William, and hence the Virginia colony, remained loyal and Royalist. Certainly, holding his commission from the king gave Berkeley a strong motive for his loyalty. Beyond that, however, the Royalist cause defended the only world Sir William knew—a hierarchical society where the accident of birth did legitimately convey both fortune and authority.

Fought near the Warwickshire town of Banbury on October 23, 1642, Edgehill was the first major armed conflict of the English Civil War.

Well before King Charles’ own fortunes finally fell with his head in early 1649, the Cavalier cause was lost for many landed lords. As the rump of the New Model Army mopped up the war for the victorious Puritan legislature, England got hotter still for the scions of the Royalist upper class. Throughout these years, Sir William waved the flag for king and colony. He actively recruited a Royalist elite for emigration to Virginia. In a time of great insecurity for Royalist landed gentry, Virginia became a beacon of safety, comradeship, and opportunity.

In the words of one contemporary observer, Virginia was “the only city of refuge left in His Majesty’s Dominions, in those times, for distressed cavaliers.” So, they came to Virginia. During the 35 years of Sir William Berkeley’s intermittent tenure as governor, many families of the English ascendancy established footholds in the colony. It became a particularly attractive home for the younger sons of Royalist families, whose own prospects were dimmed in England by the accident of birth order as well as the changing political fortunes of their families. The Royalist and Anglican colonists of Virginia, however, differed in several ways from the Puritans whose emigration created New England.

At the most fundamental level, the New England Puritans and Virginia Cavaliers were on opposite sides in the English Civil War. Not only did they not share the same vision for the English government at home, but they also did not possess the same ordered view of the world and of society. Beyond that, they came from very different parts of Britain—at a time when regional differences in society were far more culturally significant than in today’s world. While the Puritan colonists made their way to Massachusetts Bay from East Anglia, London and the counties of the East Midlands, Virginia’s settlers came to Jamestown from a southern triangle from Kent to Devon and north to Warwickshire.

The society that bloomed in the Virginia tidewater during Berkeley’s decades in office reflected the social order, regional characteristics, and ecclesiastical convictions of the people who came. In fact, it reflected Sir William’s own view of the world and of the people who inhabited it. Though the Puritans hardly believed in a free society as we recognize it today, they were from the middling sort of society—craftsmen, tradesmen, and gentry—from a part of England with a tradition of local participatory government. The men and women who immigrated to Virginia during the 1640s-60s came from opposite ends of the economic and social spectrum.

From its first flourishing under Berkeley’s dynamic leadership to the end of its colonial existence in 1776, Virginia society was a culture of a sharp division between the haves and have-nots. After all, the very nature of a wealthy elite implies a mass of folk who are not. The vast majority of those who came to Virginia had Royalist and Anglican sympathies certainly (they were not welcome otherwise), but they were rural laborers of humble origins, generally illiterate and accustomed to a humble lot in life. While they dreamed of betterment in the New World, more than 75 percent of them arrived in Virginia as indentured servants. Two-thirds of those folk were unskilled agrarian workers. All the plantations springing up beside the rivers in the rich fertile delta of the Virginia tidewater required a labor force. As the Algonquian tribes being supplanted from eastern Virginia were unavailable for employment, that labor force had to be imported.

The two decades from 1645 to 1665 saw the greatest influx of Royalist colonists, elite and lowly alike. They did not come to sample the pure air of egalitarian freedom promised by America’s founding documents a century and a quarter later. They expected to find, and accepted, the hierarchical English society that they left behind.

Privilege, liberty, and economic comfort went hand-in-hand with social status. One was either an independent gentleman or, at some level, a servant and a subject. Whatever status one occupied in the world, it was taken for granted, was simply accepted as the ordering of fate or God. Such a hierarchy evolved organically in England. It was the social legacy of feudal Norman England. In Virginia, however, this rigid class distinction was draconically imposed on the colony by Governor Berkeley and the like-minded landed aristocracy that became known ultimately as the First Families of Virginia.

From the upper ranks of English society, they came: Culpeper and Fairfax, Throckmorton and Digges, Byrd, Spencer, and Gage. Starting with a score of aristocratic families and a hundred families of the landed gentry and burghers, Virginia landed elite intermarried quickly and formed an interlocking directorate that controlled every aspect of life in Virginia from 1660 to the American Revolution.

During the Commonwealth years of Cromwell and the Puritan administration, Sir William had relinquished the office of the governor but remained at Green Spring. In 1660, with the restoration of King Charles II to England’s throne, Berkeley once again became the colony’s governor and de facto ruler. What power Berkeley did not possess in his own person lay in the Royal Council—which served as the upper house of the colonial legislature, as the governor’s cabinet and the colony’s supreme court. Perhaps just as important, the council-controlled the distribution of land, and they gave it to themselves.

David Hackett Fischer, whose landmark social history Albion’s Seed is the inspiration for this British Heritage series on the Great Migrations, uncovered just how closely political power was held in colonial Virginia. In 1660 every member of the Royal Council was related by blood or marriage to another member. When that council ended its days in 1775, every councilor was descended from at least one member of the council of 1660. The Cavaliers whom Berkeley actively recruited to Virginia during and after the English Civil War became an effective, closed, and largely despotic hereditary oligarchy.

It was quite a feudal society. Opportunities for upward mobility were restricted. More to the point, it is difficult from the standpoint of our 21st-century American ethos to understand the mindset of 17th-century colonists. Certainly, from our contemporary perspective of human dignity, human rights and freedoms and open society, the hierarchical society guarded by the First Families of colonial Virginia seems, to say the least, unattractive.

This colonial ascendancy pointedly did not believe that all men were created equal. Quite the contrary, as much as they believed in the legitimacy of their own right to wealth and power, they believed that the vast majority of people belonged to a divinely ordered underclass. It is not a giant step from such an axiom of life to a justification of race slavery.

Expansion of the plantations and the plantation-based economy required more subservient labor than Restoration England was providing. African slavery evolved and crystallized as an institution under such an economic mandate. The worldview of those who already believed in a divinely ordered hierarchical society needed little attitude adjustment to accommodate the moral justification of the institution. If it was the slave-owning class who enjoyed the economic benefit of slavery, the white underclass gained in quite a different way. With the inferiority of the black race institutionalized, the wage-laboring agrarian poor majority of the population was no longer on the bottom rung of human existence.

Colonial Virginians believed that keeping everyone in their proper place was the best way to maintain a healthy, prosperous, and growing colony. Sir William Berkeley’s most famous quote reflects his own desire to preserve that social order: “I thank God, we have not free schools nor printing, and I hope we shall not have these hundred years. For learning has brought disobedience, and heresy and sects into the world; and printing has divulged them and libels against the government. God keep us from both!”

As jarring as Governor Berkeley’s sentiment appears in the present day, however, it was an effective and very English view of his world and of the responsibility that the ruling class bore. In the context of his times, Berkeley was highly successful: Virginia did become a healthy, prosperous, growing colony under his leadership.

King Charles I, who held the throne from 1625 to 1649, was painted here by Gerrit von Honthorst in 1628.

When Sir William was 70, he had been a chief promoter, governor, recruiter, and leading citizen of the colony of Virginia for a third of a century. Always haughty, the governor became cranky and petulant as the years went by. The effectiveness of his continued tenure in office was tested by an outbreak of vigilante law over Indian policy. Berkeley’s mishandling of what became known as Bacon’s Rebellion earned him a reluctant retirement. He returned to London in May 1677 but was a weakened and defeated man. Sir William died that July and was buried in Twickenham.

When Berkeley became governor of Virginia in 1642, the colony was still a tenuous experiment of a few thousand colonists after 35 years of existence. By the time of his death, 35 years later, Virginia was the flagship colony in the Americas, with 40,000 colonists, a working economy, a functioning legal system, and established social order. Virginia was here to stay, and Sir William Berkeley had built it his way.

Certainly, the culture and operating rules of society were far different in colonial Virginia than they were in the New England strongholds of the Puritans, though both were very English societies. It is amazing that these two very different visions of life did not come into more active conflict than they did during the colonial century between Berkeley’s death and the American movement to independence from Britain. In fact, almost 200 years went by before the sons of the Puritans and the sons of the Cavaliers fought one another again in the American Civil War.

What kept the peace, and ultimately provided a framework for unity among the colonies in the War of Independence, was the introduction of a middle way of seeing life in the New World. The emigration of Quakers from the West Midlands and Wales added a vital new square to the tapestry of colonial Britain in the Americas, a piece that will be explored next issue in “The Great Migrations 3: The Quakers.”

Despite Berkeley’s attempts to diversify the economy of the colony, tobacco remained the money crop and chief export of colonial Virginia.

Green Spring

Shortly after Sir William Berkeley arrived as governor of Virginia, he acquired the property known as Green Spring, some three miles to the north of Jamestown. Over the next few years, Berkeley built Green Spring into a dynamic plantation, extending it by 1670 to a holding of about 7,000 acres.

At the end of a long, tree-lined drive, Berkeley built the manor house at Green Spring, the first Anglo-American mansion built in the colonies. The E-shaped brick manor would have been right at home in the countryside of Bedfordshire or Somerset.

Green Spring quickly became a social center for Virginia’s planter elite and an iconic political power base. After Sir William’s death in 1677, the house served as home to three successive colonial governors. The original house was replaced in 1800 with a new manor designed by famed architect Benjamin Latrobe. That home was destroyed by the Union Army in 1862, and Green Spring’s history as a plantation ended.

Benjamin Latrobe’s View of Greenspring House.

Today, the property is in the hands of Colonial National Historical Park. Little evidence remains, however, that this was once the most important 17th-century residence in the English colonies. A terraced landscape, remnants of outbuildings, and a few ancient fruit trees are all that remains of the plantation.

With the approaching celebration of Jamestown’s 400th anniversary, the exploration of historic Green Spring has taken on new significance. A nonprofit organization, Friends of Green Spring, is partnering with the National Park Service to support Green Spring’s development as an archeological site. The Friends are engaged in a major fundraising program to create an access road and visitors center in time for the 2007 celebration. Long-term, the Friends of Green Spring seek to raise resources for a thorough archeological investigation of the site and programming to promote its historical significance.

* Originally published in May 2005.

Comments