Edward I (1239-1307)

King Edward I ordered 12 monuments, known as Eleanor Crosses, to be built to honour his dead wife. So was he the most romantic monarch of all or was he a pragmatist who used Eleanor of Castile's death to further the infrastructure of medieval Britain?

In 1290 Eleanor of Castile, queen consort to Edward I, died suddenly and unexpectedly in a small village near Lincoln while traveling north to be with her husband in Scotland. It was November 28 and the cold winter chill had set in, felling a woman who had survived 16 births and several military campaigns with her husband as far afield as the Holy Land. Eleanor lay in state in Lincoln Cathedral, and was then embalmed and had her organs interred in an effigy tomb behind the altar.

Eleanor’s effigy shows a petite woman with a sweetly beautiful face, a tiny chin, and a serene smile. It is quite a contrast to the likeness of her husband, the notorious “Longshanks” made infamous to modern moviegoers by Mel Gibson’s Braveheart. A bas-relief on York Cathedral shows an extraordinarily tall and skinny man with a skeletal frame and piercing eyes, his brow in an angry frown. So it may be a shock to discover that the monstrous villain of Gibson’s factually-challenged movie was so devoted to his late wife that he erected 12 large monuments to her - one at each place where her funeral procession stopped as it brought her body south to London’s Westminster Abbey. These are the justly famous Eleanor Crosses, of which three survive and a fourth has been reconstructed.

Read more

The Eleanor Crosses throw a bright light on an otherwise obscure corner of the medieval world. For one thing, Eleanor’s husband was arguably the most important monarch between William the Conqueror and the Tudors, and the mere existence of the crosses gives evidence of his personality. Second, and more important, is the location of the crosses. For these are not “crosses” in the sense of Latin crosses - they are shaped more like rocket ships- they are crosses in that each is located at an important crossroads. Edward created them as part of a medieval road system.

The crosses cannot be understood without understanding Edward I, Longshanks, their creator. The son of Henry III, Edward came to the throne in 1272 at the age of 33 and reigned for the next 35 years. He had already established himself as a military leader, having put down a rebellion and participated in the Ninth Crusade. Upon becoming king, Edward went about annexing Wales into his kingdom, with complete success.

In 1290 he set out to absorb Scotland, first by using diplomacy, and then (in 1296) through brutal military force. Domestically, he established a sophisticated bureaucracy that could collect taxes and pay bills without his direct supervision. Edward curbed the feudal aristocracy and established the crown as something like a modern government. He supported the supremacy of the law over the king and expanded the institution of parliament. The modern English state looks the way it does largely because of Longshanks.

Edward I and Eleanor of Castille

And he loved his wife. His marriage with Eleanor was wholly diplomatic and arranged; he was 15 at the time and she was 10. By the time they were both in their 20s, however, they had very much become a couple. Most telling was that Eleanor accompanied Edward on many of his military campaigns, including his four years on Crusade. Edward depended on Eleanor, probably for advice as well as for love and support. That Edward kept Eleanor with him on these arduous journeys, even when she was pregnant and about to give birth, showed that he needed her counsel when decisions were the most difficult.

Eleanor died during the earliest stage of Edward’s Scottish intervention, characteristically rushing to her husband’s side during a major crisis. Scotland’s king had died without an heir, and Edward had negotiated a landmark settlement that guaranteed Scotland’s independence. Signed in July 1290, it called for Edward’s son, later Edward II, to marry the Scottish king’s granddaughter, 7-year-old Margaret, Maid of Norway. In October Margaret died on the voyage to Scotland, and the Scottish lords asked Edward to arbitrate claims to the succession. Eleanor headed to Scotland to help her husband with that subtle and challenging task and died on the way. She was 46.

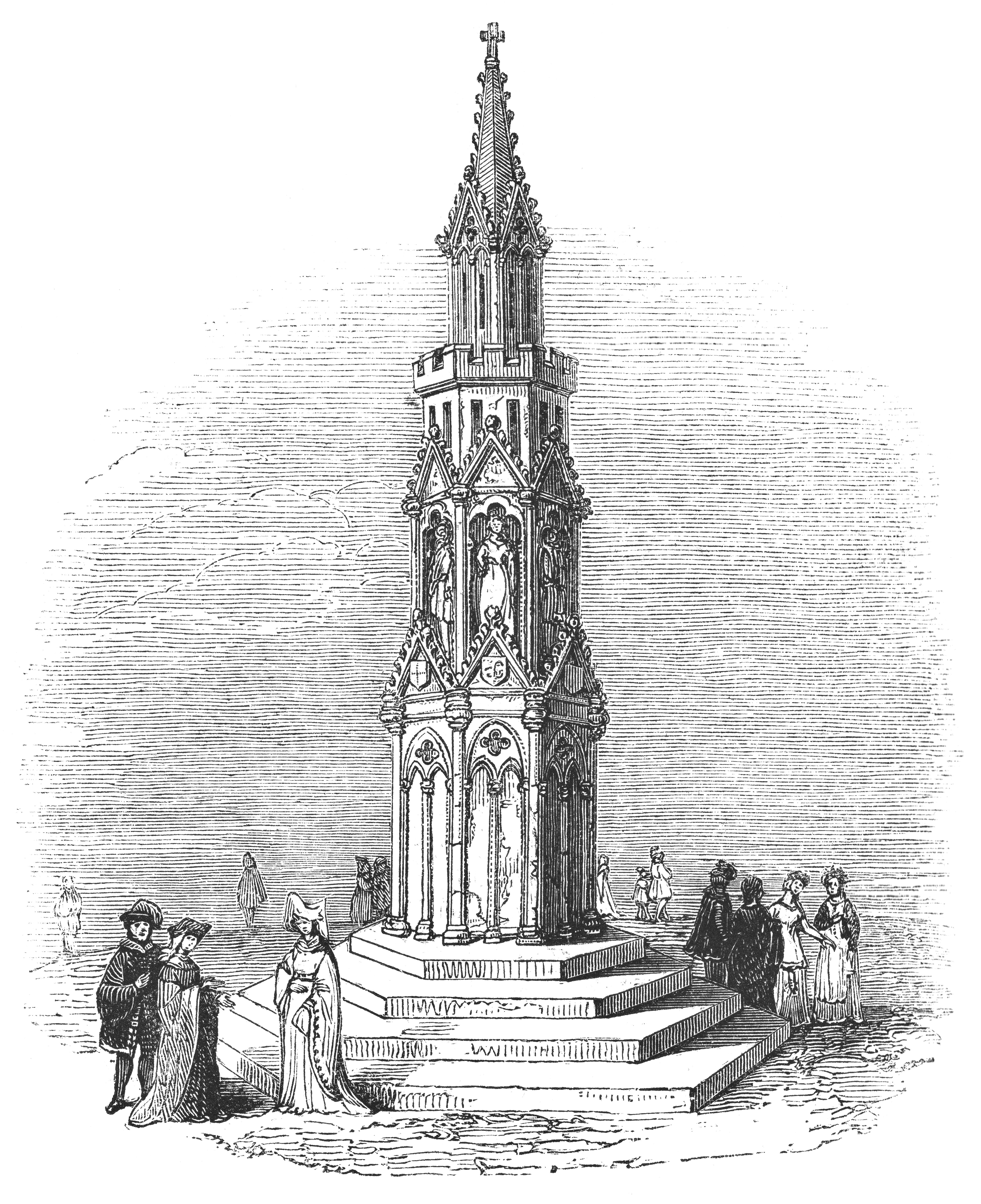

The Eleanor Cross at Charing Cross in Westminster, London, England from the Works of William Shakespeare. Vintage etching circa mid 19th century.

Edward ordered the 12 memorial crosses to be built simultaneously, in order to speed their completion. To accomplish that, each had its own designer and work crew, and each cross was therefore unique. Although all were tall four-sided pillars covered in statuary set in niches, everyone had its own take on that basic approach. Most were encrusted with saints and popes and were destroyed by the extremist Puritans of the 17th century. The three surviving crosses lack the panoply of Catholic heroes and were spared the wrath of the anti-Roman radicals. Each is very tall, between two and three stories high, carved in local stone and richly embellished in the decorated style. At the top are four statues of Eleanor, different in every one, but variants of the themes: Eleanor the Maiden, Eleanor the Mother, Eleanor the Matron and Eleanor Glorified.

Why did Edward erect the crosses? No doubt he used them as a memorial and as a catharsis for his grief. Beyond that, he intended them as a focus of prayer for her soul in purgatory. Prayers given by passers-by would hasten her entry into heaven. He could have achieved this more effectively, of course, by placing a chapel in a monastery. The funeral procession stopped at six of those, yet the crosses were placed in the nearby towns. Edward’s purpose must be understood by their locations at crossroads.

Medieval England relied heavily on its roads, and those roads received heavy traffic. Trade goods went to-and-fro on packhorses and carts; merchants traveled widely; and the nobility was always on the move, often with large retinues. Kings spent much of their time on the road, followed by huge trains of hangers-on, servants, and goods, and Edward and Eleanor traveled more than most. Yet medieval England had no road system at all, no road maintenance, no signposts, no maps to help people get around.

The Queen Eleanor cross in Northampton England. Built in 1290 to commemorate the over night resting place of the body of Queen Eleanor on the journey from Lincoln to London

Two types of roads traversed medieval England. Much of the Roman road system was still in use after a thousand years without maintenance. The roads converged on the Roman provincial capital, London, making them particularly convenient for medieval travelers. The second type of road was no road at all. It was a right of way, a traditional right to tramp over someone else’s land to get somewhere. Typically, these were the paths that villagers followed to get to their fields, with trails linking up to the adjacent village’s network. If you knew how, you could follow them from one end of England to the other. Evidently, people knew how. By 1290 many of those routes had become worn enough to be considered “roads,” with a steady stream of traffic and an inn every dozen or so miles.

Edward led Eleanor’s funeral procession southward from Lincoln on the Roman road known as Ermine Street. Picture a large crowd of courtiers riding along under dark December skies, acting sorrowful and sympathetic within earshot of their mercurial king, then laughing and complaining about the weather when out of range - a great, solemn, colorful party. They spent the first night at the town of Grantham, probably at the Angel and Royal Inn, still in business today. From there they continued down the Ermine Way to Stamford.

Read more

From Stamford, the Roman road would have led them into the Fens of Cambridgeshire, which in wet winter weather is a nasty, muddy mess. Edward instead led them southwest along with informal rights of way that have since become the A43, crossing the rolling hills of Northamptonshire to the royal hunting lodge at Geddington. This had been a favorite spot for Edward and Eleanor (Edward would never visit it again), and now is the site of the first surviving Eleanor Cross, set in a market square among thatched cottages.

Travel slowed down then, as the party wandered from village to village in the cold winter weather; villagers would peek out to gawk in wonder at the gay procession behind the solemn king and the body of the queen. The next stop was Delapre Abbey, just south of Northhampton. The cross is not at the abbey, though, but rather at a nearby crossroads, now a Northampton suburb along the busy A508. Particularly moving statues of Eleanor top this second surviving cross.

Close-up photo of the restored Eleanor's Cross outside the Charing Cross station in London, UK.

South of Northampton the procession picked up the Roman road known as Watling Street, now the A5, and spent a night at the roadside tavern town of Stony Stratford. From there Edward continued south along Watling Street to Woburn Abbey, placing the now-gone cross at the crossroads in the nearby village. Next, a particularly short day along Watling Street brought the processional members no farther than Dunstable; they probably stayed in the Augustine Priory, but again the cross went to the nearby market square. After that, another short day took them along Watling Street to St. Albans and another abbey, and again the cross was placed in the nearby market square.

Edward’s procession moved slower and slower. Instead of following Watling Street straight home—a day’s ride—he led his procession through the countryside north of London, stopping at Waltham Abbey. As with the previous three abbeys, the cross went up in the market town, Waltham, a mile away on the other side of the marshy River Lee. Now known as Waltham Cross, the town’s market still crowds around its glorious Eleanor Cross.

From there Edward and the funeral procession spent two more nights on the road. First, they followed the River Lee into the heart of London. They stayed in a neighborhood then known as Westcheap, although that name has long since disappeared from maps. The cross, destroyed in 1643, went up in a market area a block west of St. Paul’s Cathedral. From there, they followed the River Thames westward to the outskirts of Westminster, then a separate town. They spent the night at the village of Charing, ever since known as Charing Cross.

Charing Cross, destroyed by Puritans in 1643, was reconstructed in Victorian times, and now stands outside the famous railroad station—a final clue as to the purpose of the Eleanor Crosses: They form a center for commerce; they mark the way.

Edward hoped that as people followed the wandering roads from town to town, the crosses would help them find their destination. He wanted merchants to travel those roads to the markets and set up their stands—in the shadow of his fair queen. And in the communities that would form and flourish there, Edward hoped that their citizens would pause time after time to say a prayer for Eleanor.

* Originally published in July 2016.

Comments