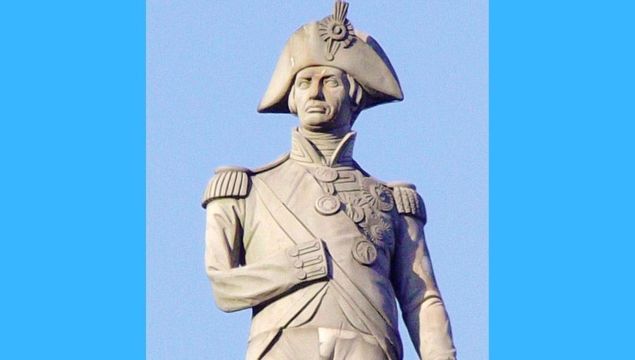

Viscount Horatio Nelson (1758 - 1805).David Holt / CC

At the National Maritime Museum's Nelson Gallery, visitors catch a glimpse of the personality of England's greatest naval warrior Admiral Horatio Nelson. Few heroes have captured the heart and the imagination more than Horatio Nelson, who died on, Oct 21, 1805 at the moment of his greatest victory.

Although a fêted national hero, he displayed common human frailty. His colorful private life, coupled with his genius and daring as a naval commander, seems to make the Nelson story irresistible to every generation.

Born in Burnham Thorpe, Norfolk, in September 1758, Horatio Nelson entered the Royal Navy in January 1771 at the age of 12. He showed early promise, passing his lieutenant's exam more than a year under the official age in 1777 and being made post-captain at the age of 21. With his own command, Nelson was in a position where his personal skills and bravery would be noticed.

Read more

The two sides of Horatio Nelson

Two paintings in the possession of the National Maritime Museum portray this fascinating but complicated character. The first, begun by Jean Francis Rigaud in 1777, was not completed until 1781 when Rigaud had to alter it to reflect a sitter who had not only been promoted but also had lost weight through illness while on duty. However, Rigaud certainly captured Nelson's determined spirit, keen eye, and a strong sense of self-confidence. These qualities gave him a presence that won the attention of nearly all who met him. In fact, Nelson's charisma soon won him a very influential friend.

A young Lord Nelson by Jean Francis Rigaud

The Prince of Wales, who was then a young midshipman, observed Nelson on board Lord Hood's flagship. The future King William IV described Nelson as 'the merest boy of a captain I ever beheld.' The young prince recalled: 'His dress was worthy of attention. He had on a full laced uniform: his lank unpowdered hair was tied in a stiff hessian tail of extraordinary length; the old-fashioned flaps of his waistcoat added to the general quaintness of his figure ... I had never seen anything like it before.' However, Prince William went on to add, there was 'something irresistibly pleasing in his address' and the young royal sensed that Nelson was 'no ordinary being'.

The second image of Nelson is very different. Painted nearly 20 years later, it shows the battered and be-medalled hero that we have come to know so well. Nelson agreed to sit for Lemuel Francis Abbott, who produced several variations of his original portrait, updating the Admiral's decorations and appearance as appropriate.

At the original sitting, Nelson was still in great pain from the amputation of his right arm. His face shows the marks of illness, fatigue, and the strain of long periods at sea. But although now almost blind in his right eye, Nelson's features reflect his zeal and indomitable spirit.

His portrait does not belie the more personal pains he suffered and his struggle with his own conscience. Now passionately in love with Emma, Lady Hamilton, wife of the aging Sir William Hamilton, Britain's ambassador at Naples, he realized that his own marriage was effectively over.

Lord Nelson by Lemuel Francis Abbott

Nelson's attire tells us something else. He had acquired a reputation for vanity, which sometimes got the better of his dignity. Caricaturists such as James Gillray made fun of Nelson's desire to cover himself in medals and orders in public. His embarrassed fellow officers described him more like a prince of the opera than the hero of the Nile. When presented with a 'Chelengk', or plume of diamonds, by the Sultan of Turkey after that battle, he insisted on wearing it pinned on his cocked hat. The decoration contained a small mechanical device that, when wound, made its center rotate in a clockwise motion!

For all his quirky personality traits, his charisma and bravery as a naval commander never came into question. Nelson always led his men by example and from the front. He first made his name at the Battle of St. Vincent in February 1797. During this battle, although a commodore, he led a boarding party across first one enemy ship, and then proceeded to use that as a bridge to capture yet another.

In July the same year, he was personally involved in a boat action off Cadiz. He later recalled: 'This was a service, hand to hand with swords.' The artist Richard Westall vividly recalls that night and dramatically captures the intensity of the fight. Nelson's coxswain, Sykes, standing on his right, saved the admiral's life twice that night by placing himself between Nelson and enemy cutlasses. On the second occasion, Sykes was wounded badly in the process. Apart from illustrating Nelson's personal bravery, this incident shows the depth of the loyalty he inspired in his men, they were quite literally prepared to die for him.

Nelson also showed a genius for taking daring but calculated risks. He broke rules and openly disobeyed his superiors when he thought the need arose. At the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801, Admiral Sir Hyde Parker, on his flagship some way off from the heat of the action, thought that the British were losing the day and hoisted the signal 'Disengage action'. From his own position, Nelson, Parker's second-in-command, could see the battle turning his way. When the Commander-in-Chief hoisted his instruction, Nelson purposefully put his telescope to his blind eye and exclaimed, 'I really do not see the signal!'

He fought on until the Danish surrendered. This single act, if things had gone wrong, would have meant immediate disgrace and court-martial. But Nelson trusted his own judgment and was proved right. After the battle, Hyde Parker embraced a weary Nelson, grateful that his second-in-command's insubordination had saved the day.

Nelson & Emma Hamilton

Away from the heat of battle, however, Nelson displayed a more susceptible side. Now separated from his wife forever, he bought a house in Merton, Surrey, and lived there with both Sir William and Lady Hamilton until Sir William's death in April 1803. From then on he spent his few remaining periods ashore in the tranquility of the home he openly shared with Emma and their daughter Horatia, who, although born in 1801, lived with a foster mother until Sir William died.

Influenced perhaps by Emma or even his travels to foreign ports, he developed a taste for the grand and splendid, and the design of his personal china, also now on display in the National Maritime Museum, reflects the extravagant side of this complicated man. His full coat of arms and the dates of his victories decorate each piece of the service.

When touring England with the Hamiltons in 1802, Nelson visited the famous porcelain factories at Worcester and ordered what is now known as the 'Horatia Service'. Decorated in a rich Imari pattern, it bears his four crests. The service took so long to prepare that it is doubtful whether he saw it at Merton before he left England for the last time in September 1805. One thing is certain: when he and Emma entertained, which they did often, the dinner table laid out with his china and silver services that had been presented to him must have looked stunning.

Perhaps the most personal relics intimately associated with Nelson symbolize the undying love he finally found with Emma Hamilton. Shortly before he left for Trafalgar, Nelson and Emma exchanged betrothal rings, in the form of clasped hands, at a private ceremony at which they also took communion. Although their relationship was the talk of society, in Nelson's eyes, he and Emma were married.

They both wore their rings constantly. Removed from his finger after his death, Nelson's ring was returned to a distraught Emma Hamilton. Both rings are currently on display in the National Maritime Museum's Nelson Gallery, having been reunited for the first time since 1805.

Nelson's last battle

Nelson sailed from England for the last time that same year. The whole fleet rejoiced that he was to be their Commander-in-Chief. He confided in his captains, now affectionately referred to as his 'band of brothers', who knew exactly what he wanted them to do. After a long chase, Nelson finally caught up with the combined fleets of France and Spain on the morning of 21st October. As he had planned, the British fleet sailed toward the enemy in two lines, thus cutting through the combined fleet so that the rear and center sections would be overwhelmed before the vanguard could turn and assist.

At Nelson's instruction, and to 'amuse the fleet', the most famous signal ever flown at sea was now hoisted. It read: 'England expects that every man will do his duty.'

Read more: Yorkshire's Cistercian abbeys

As the battle raged around him, Nelson walked Victory's quarterdeck with Captain Thomas Hardy. At approximately 1.15 pm a musket ball fired from the French ship Redoubtable struck him in the left shoulder. It pierced one of his lungs and lodged in his spine. Nelson knew that his wound was mortal, and exclaimed 'They have done me at last, my backbone is shot through!'

An employee poses with a large fragment of the Union Jack flag believed to have flown from Lord Horatio Nelson's ship, the HMS Victory at the battle of Trafalgar (est. £80,000 - 100,000) at Sotheby's on January 11, 2018 in London, England.

Carried below, he requested that his hair be cut off and given to Lady Hamilton. He died at 4.30 pm, after having learned that he had won a great victory.

Perhaps the most famous Nelson relic of all is the uniform coat he wore on that fateful day. The bullet hole and torn epaulet are plain to see. Before the battle, Nelson refused to change into a less conspicuous coat, as suggested by officers concerned for his safety. Perhaps a premonition had told him that he was meant to die at the moment of his greatest victory. Immediately before the battle, he shocked one of his captains by saying, 'God bless you, Blackwood, I shall never speak to you again.'

And what of his legacy? Trafalgar gave the British Navy supremacy of the seas for nearly a century. His death brought about an outpouring of public grief hardly equaled to this day. Fascination with his life, both personal and public, had begun. In death, Nelson had finally achieved his greatest ambition, immortality.

Read more

* Originally published in Sept 1998.

Comments