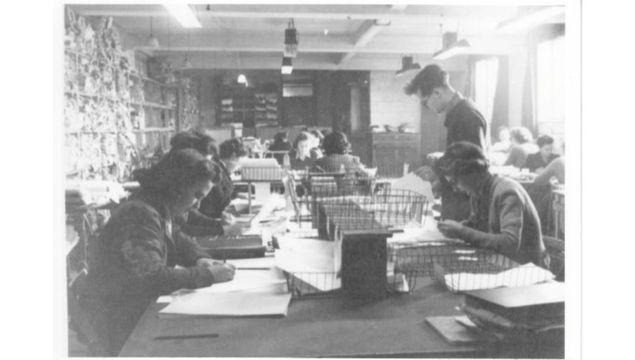

Codebreakers at work at Bletchley Park, during World War II.UK Gov / CC

Perfectly coiffed and groomed to dash off to a meeting, Ruth Bourne sits in her North London home and modestly explains how she helped save Western civilization, one letter at a time. Bourne was 18 years old in 1944, fresh out of her WREN (Women’s Royal Naval Service) training when she was assigned to SDX.

“What’s SDX?” she asked. “SD is Special Duties, and X, we can’t tell you,” was the reply. Soon she found herself at Eastcote, an adjunct to Bletchley Park, Britain’s code-breaking center.

Bletchley Park was once the country home of the wealthy Sir Herbert Leon and his family, who added to it over the years in a mix of architectural styles. By 1938 the mansion was for sale, and the Government Code and Cypher School needed a safer home. Fifty miles from London, Bletchley was close to roads and railroads. It was refitted as a center to decode messages produced by the infamous Enigma machine, a devilishly complicated German encoding device that resembled a large, overgrown typewriter.

Read more

The Poles had cracked Enigma in 1931, but when war broke out and the codes changed every 24 hours, it was evident that more effort had to be brought to bear on it. And so to Bletchley came an assortment of mathematicians, military experts, historians, bankers, musicians, chess masters, and people who did the Times Sunday crossword in ink. Huts sprang up on the grounds where code-breakers worked, sweltering in summer, freezing in winter, in a haze of cigarette smoke. Others labored in centers close by, including Eastcote.

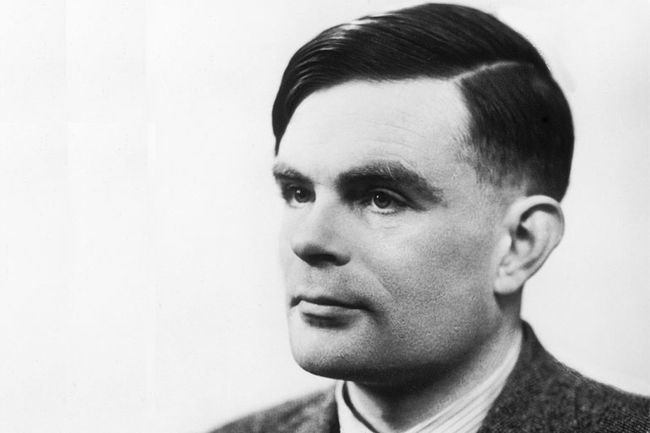

Chief among the code-breakers was mathematician Alan Turing, who invented the Turing Bombe, a device that turned the letters produced by Enigma into legible German. With its rows of wheels and dials, it is tempting to call the Bombe a prototype computer, but it is in fact an electromechanical device that carried out a systematic search to find combinations on the Enigma. There were 150 million million million possible settings to choose from!

Alan Turing.

Meanwhile, Bourne and her mates learned that they would be doing very special, unspecified work. They were told:

“You won’t get any promotions or special pay. Hours are very antisocial, and once you’ve signed in, you can’t leave.” They signed the Official Secrets Act and were told they were going to be breaking German codes.

Every employee of Bletchley—there would be some 10,000 of them over the years—signed that important document, and apparently not one broke the silence it dictated. At least one couple met and married while working at Bletchley and waited until 1971, when the Act was revoked, to tell each other what their work had been there. Bletchley’s neighbors were blind and deaf to the stream of traffic that went in and out on a regular basis.

“It only took one person to give the game away,” Bourne said. “There were big posters up: ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives,’ and ‘The Walls Have Ears.’”

She and her mates worked in shifts in a huge room containing 12 Bombe machines.

“There were very high, slitty windows so nobody could see in. We didn’t know whether it was day or night,” she recalled. Working in pairs, they attached wheels, connected plugs and waited for results. If they thought they had found a legible message, they wrote it down and gave it to a checker.

“We spent one day working on the machines and another checking the stops to see if they were good enough to send into the huts, where they were picked up by code-breakers and put on other machines,” said Bourne. Workers at the machines had to stand; checkers could sit. “I never heard anyone talking about the work they did outside the block, except one girl saying, ‘Are you sitting or standing?’” At the end of every run, they pulled off the wheels, pulled out the wire brushes with tweezers and put them on racks for the next run. The codes changed at midnight, sometimes sooner.

“You had to be very accurate,” recalled Bourne. “You had to make sure the brushes weren’t touching each other to make a short circuit, and you had to make sure you got your drums in the right position. The hardest thing was plugging up, so you didn’t get the plugs bent and also that you got the right letters connected to the right letters.”

Shifts were 8 a.m. until 4 p.m., 4 until midnight, one day off, then midnight until 4 a.m., each with a half-hour meal break. The last shift was called the “relief shift.” However, Bourne said, “None of us were relieved except when it was over.”

Meanwhile, they had the usual military duties, which included scrubbing barracks and kit inspection. Still, life wasn’t all grim. There were concerts, a tennis court, Scottish country dancing and a chess club. Some of the code-breakers put on a production of The Marriage of Figaro. Trucks took them into London to the Stage Door Canteen in Piccadilly and the theater, where they collected autographs from such stars as Vivien Leigh and Michael Redgrave.

Read more

Bourne and her co-workers never knew what the messages contained. One code-breaker learned that Jews were being processed for concentration camps; another intercepted a message to the German quartermaster complaining that the Army-issue underpants split when the wearer sat down. One received news of the Normandy landings, of which Winston Churchill said, “No single operation out of the world war was so dependent on Bletchley as the Normandy landings. Indeed without the work which was done here, there is no way the landings could have gone ahead, let alone succeeded.”

Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Motorcycle couriers took the translated messages to Bletchley, whence they went directly to the War Rooms by radio. As many as 35 or 40 bikers might come through the gates in an hour. Churchill could read Adolf Hitler’s mail before Hitler did. It was estimated that Bletchley’s work shortened the war by two years.

At the end of the war, Churchill ordered the Bombes destroyed so they didn’t fall into the wrong hands. Bourne and her mates were delighted to do this, happily attacking them with soldering irons. “We didn’t love our machines,” she said.

Recently, Bletchley Park opened to the public. Some 440 volunteers serve to assist the 500 to 600 visitors who tour daily. Visitors can purchase a yearly passport and come back as often as they like. It could take two days to view the whole display properly. The mansion contains a collection of wartime memorabilia, a reference library and a tribute to Churchill and the code-breakers.

A guided walk around the grounds tells the Bletchley Park story. The huts are deteriorating, and there has been no effort made to modernize them. One is dedicated to special liaison naval officer Ian Fleming and the top secrets he worked with that would inspire his James Bond novels. Fleming launched Operation Goldeneye, and with language straight out of a spy novel, he described exactly how to board a U-boat and capture Enigma codes, as one brave soul actually did. Hut 4 tells the story of the German spies who parachuted in, were captured, and turned into double agents.

Some of the most important work was done in Hut 6, which in importance was probably second only to the Cabinet War Rooms. It was devoted to the German army and navy code-breaking.

H Block holds the National Museum of Computing, whose star display is a rebuilt Colossus, said to be the world’s first computer. Guides explain that Hitler and his high command didn’t use Enigma, but a different, more complicated machine called Lorenz. In 1943, Tommy Flowers, with help from Turing and mathematician Max Newman, created Colossus to decipher Lorenz’s teleprinter messages. This model, which took 14 years to rebuild from a few diagrams and some black-and-white photographs, clicks and blinks as if it were receiving another message from Berlin. There are computers at the museum that fill whole rooms as well as desk models. Working flight simulators let those of all ages play pilot.

Six Bombe machines fill Hut 11, showing the conditions in which the Eastcote and other workers operated. “They wondered if women could operate the machines, but they thought they’d give it a go,” said guide Kelsey Griffin.

Alan Turing’s office is re-created in Hut 8, down to the gas mask he wore as he cycled to work because he was subject to hay fever. Turing, to whom the term “tortured genius” could aptly be applied, spent the later war years working in Washington, D.C., and did not return to Bletchley. Hounded later in life for his sexual proclivities, he committed suicide by eating a cyanide-laced apple, a sad ending to a life stranger than fiction. His statue at Bletchley is made up of a half-million pieces of layered Welsh slate, and seems to be writhing with electrical wiring.

Read more

A post office that used to be a top-secret mailroom has a display of items from the 1940s and sells commemorative stamps. Visitors can mail an envelope of “spy secrets” and wartime recipes. Other displays at Bletchley include toys, model boats, vintage vehicles, a model railway, a garden trail and an incredible collection of Churchilliana. The cinema shows old newsreels and Pathe films.

Germans and Japanese are among the visitors. “We have a number of German visitors,” Griffin says. “Bletchley Park was responsible for shortening the war by two years for them as well.”

Churchill famously called the Bletchley Park code-breakers, “The geese that laid the golden eggs and never cackled.” But for the WRENs, he had a special accolade.

“He had a way of using birds as metaphors,” Bourne explained. “He sent us a telegram which was pinned up at Eastcote: ‘Glad to hear the hens are laying so well without cackling.’”

Visiting Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park Mansion.

For information about Bletchley, see www.bletchleypark.org.uk or call 01908 640404 for 24-hour recorded information. Not all the displays are open at the same time; It’s a good idea to check in advance those you want to see.

Bletchley Park is always in need of funding. Donations to Bletchley Park Trust, The Mansion, Bletchley Park, Milton Keynes, MK3 6EB are welcome.

* Originally published in 2016.

Comments