Producing the best of British comestibles is the ardent mission of the Edible Garden Show, on a fast track to become a major annual horticultural event.

Runner beans, heritage seeds, and secret family recipes, a gourmet tour of rural Warwickshire’s historic houses and gardens.

* Originally published in 2016.

Lettuce is the most popular vegetable grown in Britain, followed by runner beans and carrots,” confided David Thornton, secretary of the National Vegetable Society. “Herbs aren’t particularly popular with our members,” he added. “They think they are a bit of a joke vegetable.”

There’s no doubting the deep-rooted passion Brits have for gardening, from the proverbial backyard plot to the swaggering displays of stately homes. And in recent years there has been an overwhelming call to trowels to “grow your own,” maybe strengthened by tight economic times. The UK vegetable seed market has hit a historic high of £60m a year; that’s 70 percent of the total seed market. While the country isn’t about to dig up all its flowers, the demand for traceable, local, organic, homegrown food is burgeoning faster than Jack’s magic beanstalk.

Nowhere is all this more apparent than at the Edible Garden Show, where Thornton and his colleagues were encouraging people to join their 3,000-strong society and grow better vegetables. The show launched in March 2016, at Stoneleigh Park in Warwick-shire, and attracted nearly 11,000 visitors over three days. It’s set fair to be a major annual event on the horticultural calendar.

Read more

The range of interests was vast: from pig rearing to allotmenteering and edible ornamentals, with demonstrations on everything from goat milking to bread baking. For the inside track on Britain’s food and garden scene, chat to the folks from the British Beekeepers Association, jam and pickle makers, the Large Black Pig Breeders Club, the Poultry Club of Great Britain. “Ask me about compost,” it said on master composter John Vincent’s badge; I dared. Our 40-minute chat is too long to relate, but the tip stuck that, “shredded private letters are good. It gets rid of the evidence.”

SIÂN ELLIS

If you are here, the show could offer a gustatory prelude to a gourmet tour of rural Warwickshire’s historic houses and gardens—so often bypassed by visitors more fixated on Shakespeare’s Stratford. Time was, a visit to a stately home for its heritage was sufficient. Now, at Warwickshire’s finest country estates, at least, the emphasis is also on feeding you with fare grown on the premises or showcasing local specialties.

Horticulture, history, and hearty living on the menu

Begin six miles northeast of Stoneleigh at Garden Organic Ryton, a pioneer of the modern gardening mood. The seeds of the UK’s leading organic-growing charity were sown some 50 years ago and, as so often happens with eccentric ideas, they’ve blossomed into the mainstream. Prince Charles is a patron.

Across 10 acres you can wander through more than 30 small, themed gardens—herb, bee, bio-dynamic, vegetable, soft fruit, paradise—that show how to put organic principles into practice. Most thought-provoking is the Heritage Seed Library, which works to save historic and heirloom vegetables from extinction. “Europe” is to blame, of course. “In the 1970s, a series of regulations made it an offence to sell the seeds of vegetable varieties not on the National List or in the European Common Catalogue,” gardener Claire Cowie explained as she showed me around. “The process of listing is costly and time-consuming.”

Thus an estimated 2,000-plus vegetable varieties have vanished, thanks to European Union and market forces. People who join the Heritage Seed Library—which conserves more than 700 varieties associated with the British Isles and Europe—get around the legislation by swapping seed.

Garden Organic Ryton, unsurprisingly, boasts a 100 percent organic restaurant that serves, according to season, mouth-tinglers like courgette and pepper pasta, and fruit crumble.

Next on my itinerary was National Trust-run Baddesley Clinton, 18 miles west: a picturesque, moated, medieval manor house that gently glows grey-gold with sunshine held captive in its stonework when end-of-day shadows creep.

The gardens reflect earlier needs to be self-sufficient, with fish pools dating back to the 1400s. And today’s walled garden may be filled with floral pleasers, but the vegetable garden works hard for a living.

“It’s a show garden, too. People can see plants in neat rows,” Baddesley Clinton’s chef, Mark, told me. “Until,” he smiled, “I go out and pick things.”

At different times of the year, asparagus, artichokes, calabrese, salads, strawberries and orchard fruits feature on the restaurant’s weekly-changing menus, with butternut squash pie an autumn favorite. All are part of the “plot to plate” policy of serving the freshest fare.

End-of-day sunshine casts a warm glow over the stonework of Baddesley Clinton. In Elizabethan times, the country house held darker secrets.

But there’s also a darker type of plotting that grabs the imagination here. For the 500 years prior to 1940, Baddesley Clinton was home to the Catholic Ferrers family, and during the Elizabethan era, the house was a sanctuary for persecuted Catholics. Tripping through genteel, wood-panelled rooms, it’s not long before you come upon edgy secrets. No fewer than three priest’s holes have been found, including one in the medieval sewer that can be viewed via a glass panel in the kitchen floor.

In the late 16th century, while owner Henry Ferrers was in London, the house was occupied by two fervent Catholic sisters named Vaux, and nine Jesuit priests were based here. It’s thought the priest’s holes were constructed by the greatest exponent of the art, Nicholas Owen, a servant of Father Garnet, the Jesuit Superior. Baddesley Clinton was under surveillance by pursuivants—priest hunters—and on at least one occasion, in October 1591, they came calling: tapping at walls and floorboards. This time, the priests, standing in water in their underground den for four hours, were lucky. The pursuivants went sniffing for Catholics elsewhere.

You can continue the story of persecutions at Coughton Court, 18 miles south near Alcester. Quiet gardens, watched over by the imposing Tudor gate tower, wrap you in seclusion; or maybe wary spirits are even now peering down to gauge friend or foe.

SIÂN ELLIS

The Catholic Throckmorton family has lived here for more than 600 years—their portraits congregate on the staircase—and were among the prominent dynasties that kept the “Old Faith” alive after Henry VIII’s break with Rome. They endured fines and imprisonment for their recusancy, and Francis Throckmorton was executed in 1584 for involvement in a plan to put Mary, Queen of Scots on Elizabeth’s throne. The family was related by marriage to the Catesbys and Treshams, future Gunpowder Plotters. You can hear the historic alarm bells ringing.

“A lot of action took place in the Midlands,” said volunteer guide Vic Avis, as he unfolded the drama of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605 to eager listeners. In short: the Throckmortons had temporarily rented out Coughton Court and one of the chief plotters, Sir Everard Digby, was in residence. Lady Digby, the Vaux sisters, Fathers Garnet and Tesimond, plus Nicholas Owen waited here for news of the attempt to blow up King James I and parliament.

On Malt Mill Lane, Alcester (left), Tudor merchants’ houses lean in for a chat with red brick cottages. At Coughton Court (right), climb the tower to the rooftop for far-reaching views across the Warwickshire countryside.

When they heard it had failed, they quickly dispersed.

“Owen was later tortured and died on the rack, but he never revealed where he had built his network of priest’s holes. He was canonized in 1970—it took a while,” Avis concluded.

Meanwhile, the Throckmortons did much to help the restoration of Catholic liberties in England, and though priest’s holes and portraits still bear witness to a turbulent past, the home today is full of bright color. The award-winning gardens, in particular, are a joy, featuring Throckmorton daffodils, a walled garden of themed rooms, and a glorious rose labyrinth. Do sample the home-baked cakes and local ice cream before you leave.

On the three-mile drive to our final destination, Ragley Hall, you might pause at the quaint Tudor merchants’ houses and Victorian needle makers cottages of Alcester. Then, it’s full-on admiration for the Palladian splendor of Lord Hertford’s mansion, the family home for nine generations. The story here is not of gunpowder and plot, but of Seymour ancestors’ public and military service.

“Ragley” derives from the Saxon for “rubbish dump”; how times change. The hall captivates with James Gibbs’ Baroque plasterwork, James Wyatt’s Red Saloon, paintings and porcelain. There are also modern surprises, like Graham Rust’s huge mural, The Temptation, completed in 1969 (spot family members, including the 8th Marquess of Hertford as a naked Neptune).

The fun continues in the gardens, which alongside renowned spring bulbs and roses feature the Jerwood Sculpture Trail. Likely you’ll encounter a galloping crusader, a mysterious cloaked figure and many more esoteric creations.

Ragley bills itself as “Warwickshire’s most sustainable country estate” and few would argue. Arable, vegetable, beef and sheep farming take place across the 3,500-acre home farm and Ragley Estate Meats, to be found at nearby Hillers Farm Shop, will tempt you with “secret family recipe” pies and traditional sausages. Here’s to hearty living, as well as history and horticulture.

Plotting and planning

Begin to plan your visit with a look at withinwarwickshire.co.uk.

The Edible Garden Show 2012 takes place at Stoneleigh Park, March 16–18. theediblegardenshow.co.uk

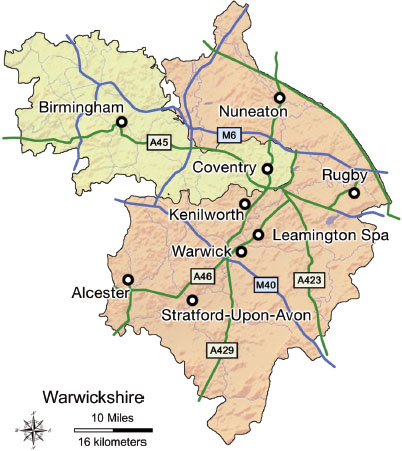

Getting to Warwickshire

Traveling by car from London, head straight up the M40 or M1/M45. Rail options include London (Euston or Marylebone) to Stratford-upon-Avon or Henley-in-Arden; London (Euston, Marylebone, Paddington) to Leamington Spa. nationalrail.co.uk

Hearty living

For a four-star treat that epitomises “history, horticulture and hearty living,” stay in the Neo-Gothic mansion that is Ettington Park Hotel, Alderminster near Stratford-upon-Avon. There’s heritage dating back to Saxon times, and landscaped gardens in 40 acres of grounds. Food is locally sourced, herbs come from the garden, and dinner, bed and breakfast packages include the chance to sponsor an estate fruit tree—you’ll see it planted and a plaque unveiled. handpickedhotels.co.uk/hotels/ettington-park-hotel.

Also drop in at The Bell gastro pub (with “posh” B&B), Alderminster, for a goodly meal and pint. The cozy 18th-century former coaching inn is part of the Alscot Estate and menus feature estate produce, including game and lamb. The locally brewed Alscot Ale is an easy-drinking blonde ale. thebellald.co.uk

Comments