The WyeGetty: Images

Messing About in Britain’s Favorite River Valley.

The market town of Ross-on-Wye, wedged onto a sandstone cliff on the Herefordshire border with Wales, casts a winsome spell for miles around with its lofty church spire. From the A40 it appears like an island rising over the river, and beguiling Tudor timbered houses, a 17th-century sandstone market hall, antiques shops and pubs will tease you to visit for an hour or three.

It’s claimed that Ross was the birthplace of the British package tourism industry, after the local rector, Dr. John Egerton, began taking guests on boating excursions along the River Wye in 1745. The jaunts caught on and soon artists, writers and the whole beau monde were swooning downriver past castle, abbey and enchanting cliff scenes, on the fashionable Wye Tour to Chepstow.

Read more

Siân Ellis

“If you have never navigated the Wye, you have seen nothing,” declared William Gilpin in his Observations on the River Wye (published 1782). The high priest of the Picturesque Movement, which celebrated all things wild and ruined like nearby Tintern Abbey, had produced an immediate bestseller. Everyone from William Wordsworth to J.M.W. Turner came to be inspired.

Perhaps, then, it is not so surprising that more than 250 years after eager Dr. Egerton launched his boat, the Wye came out on top in a vote for the public’s favorite river in England and Wales. Scenic and unspoiled, the Wye still makes a great tour.

Its source is actually way up country from Ross, in the spongy blanket bog of Plynlimon’s slopes in Ceredigion. An unpromising start, to be sure, and hardly worth a trudge except for the fresh air and exercise. But muddy bubbles soon shape-shift into a beautiful route that out-dazzles the Wye’s mountain-born sisters, the Severn and Rheidol.

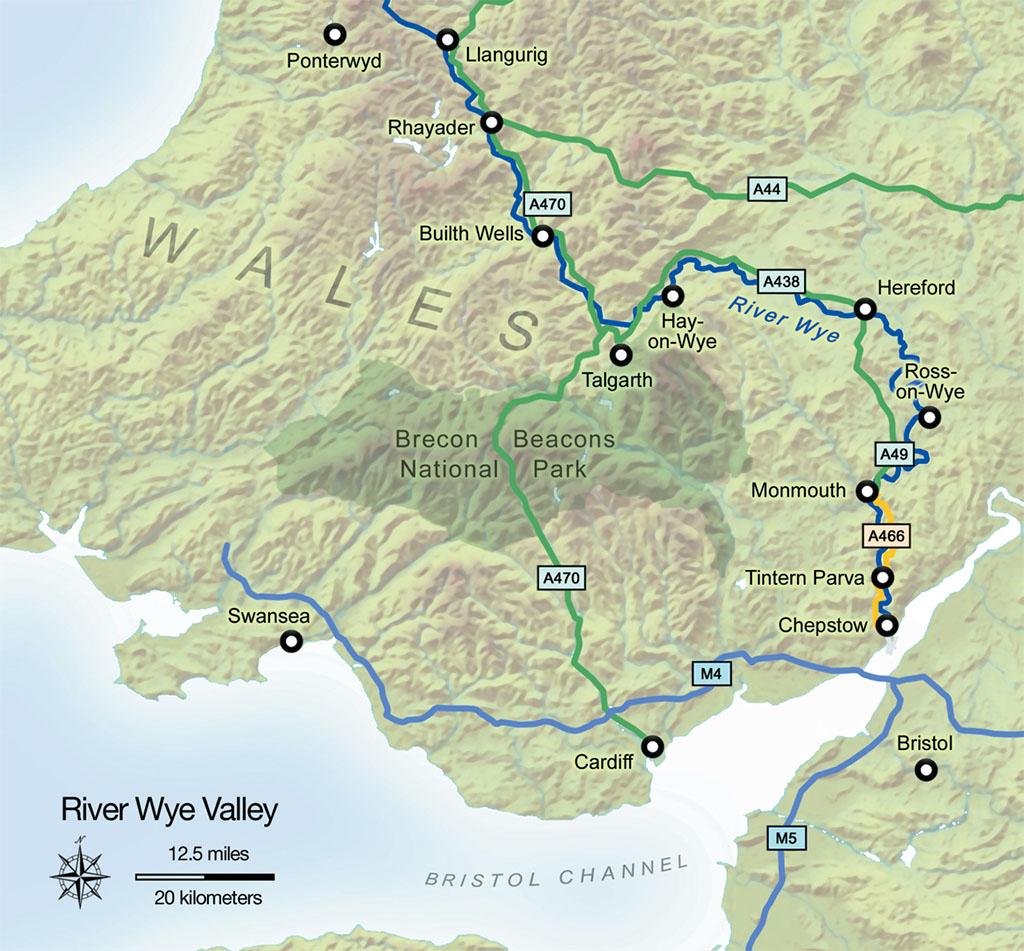

There is a Wye Valley Walk you could hike to take in many of the river’s sights as it wends some 134 miles all the way to Chepstow. Fast and rocky in its upper reaches, the Wye later blossoms into voluptuous bends and horseshoes, unfolding through Powys and Herefordshire, and staking the border between Wales and England through Monmouthshire and Gloucestershire. If you haven’t brought your walking feet, simply step out of the car at a chosen stretch and dabble your toes in the flow of history, of Marcher lords and Welsh princes, Wordsworth and Edward Elgar.

Assuming you haven’t toiled up Plynlimon, Llangurig is the first village on the upper Wye—with a 15th-century church that boasts the royal pew of Prince Albert (later King George VI) no less and a scatter of houses and pubs surrounded by sheep country. Still too remote? The first town, about 20 miles from the Wye’s source, is Rhayader: in Welsh, Rhaeadr Gwy, “waterfall on the Wye.” The magnificent waterfall has long gone, cleared to widen the river and build a bridge in 1780, however the wild, boulder-strewn nature of this stretch seems characteristic of the town’s boisterous past.

Native Welsh princes and Norman Marcher lords, keen to control the crossing of the Wye, tussled here early on, and later, in the 1840s, Rhayader was the stage for the Rebecca Riots. The imposition of tollgates on roads used by cattle and sheep drovers headed for markets in England so inflamed the locals that the Rebeccas—farmers disguised in women’s clothes and with their faces blackened—demolished them. Such antics did the trick and most of their grievances were addressed following a Commission of Inquiry.

Agriculture remains hugely important to the local way of life, and tourism is centered on outdoor activities. Mountain bikers love to bomb down the old railway track to the Elan Valley, where Victorian engineers created reservoirs to supply water to the thirsty burghers of Birmingham.

Look out for native red kites, too: This area has been at the heart of their resurgence from near extinction, and “feeding time” at Gigrin Farm on the outskirts of Rhayader, attracting up to 600 raptors, is a thrilling spectacle.

Onwards, the Wye tumbles through Penddol Rocks rapids to Builth Wells, whose Welsh name, Buellt, paints a picture of “the wild ox of the wooded slope.” Aptly, it’s home to the annual Royal Welsh Show in July, when the agricultural world parades its best beasts before some 200,000 visitors.

The “Wells” part of the town’s name was added after mineral waters were discovered here and a brisk spa trade emerged, along with a Victorian and Edwardian building boom. Now, Builth has an old-fashioned feel, set against the glowering backdrop of the Black Mountains. There are a few eateries along the main street, but otherwise head out for the increasingly softer, picture-postcard stretches of the Wye.

With a leisurely loop, we’re soon in Hay-on-Wye, where the infamous Norman Marcher lord William de Breos II built the castle that overlooks the creaky little streets. These days the word is mightier than the sword, Hay being renowned for its second-hand bookshops and literary festival in May that attracts top writers.

GREGORY PROCHE

Take a tip and come out of season for a quiet browse—you’ll find everything from astronomy and antiquarian tomes to Welsh interest and travel. Richard Booth’s Bookshop on Lion Street (it was Booth’s vision that created the bibliophile’s paradise) is a treat with its reader-ready armchairs and the café does a good lunch of Welsh rarebit. Trot a few minutes’ out of town and the riverbanks morph into unexpectedly shingly, beach-like scenes, complete with paddling tots and canoeists.

Downstream of Hay, the Wye relaxes into meandering mood. Due to an act of parliament in the late 17th century, there is a public right of navigation, hence the many watercraft—sometimes at odds with anglers whose Zen-like, long-distance gazes and keen concentration can be known to falter. The river is home to species like trout, grayling and salmon, but to preserve stocks, any Wye-caught salmon and sea trout must be released again.

Wiggle on to Hereford where the 11th-century cathedral overlooks the river, unnoticed by anglers lost in their watery worlds. Edward Elgar wrote some of his music while in the city, and there’s a good day’s worth of sightseeing here, including the fine black-and-white Jacobean Old House.

Then we’re in Ross-on-Wye, where The Prospect public garden, opposite the church, lives up to its name by revealing fine views over the river curving 100 feet below. The Prospect was created by John Kyrle (1637–1724), a major benefactor of the town whose work was immortalized in verse by Alexander Pope: “Who taught that heav’n directed Spire to rise? The Man of Ross, each lisping babe replies.”

Drop into the visitor center in the Market House for displays and information, and do check on opening times of Wilton Castle: a newly restored 12th-century Marcher stronghold a short walk along the river, “its shattered tower and crumbling wall combine with (the Wye’s) wild luxuriance to form a scene of great picturesque beauty,” as one 19th-century tripper enthused.

To do in The Wye

If you are coming by rail, there are train stations at Chepstow and Hereford. For freedom and ease, however, travel by car. From London, it’s the M4/M48 and A466 for Chepstow and the southern Wye Valley. Pick up the A40 to Ross-on-Wye. To join the river in its upper reaches, take the M40 from London, then A40 around Oxford, picking up the M5 toward Worcester and A44 cross-country to Rhayader, with the A470 heading up to Llangurig.

Siân Ellis

Nearby Goodrich Castle muscles its way to prominence on a wooded hill watching over the passage of the Wye. Begun in the 11th century, the ruddy red fortress eventually succumbed to the threat of Parliamentarian mortar attack in 1646—Roaring Meg, the only surviving Civil War mortar, is now a visitor attraction.

At Lydbrook, seats line the riverbank for watching the world go by. Then, through horseshoe bends beneath limestone cliffs and ravine woodlands, the river snakes between Symonds Yat East and West, two hideaway hamlets that can be reached by squeaky-narrow roads. Savor a cream tea on the water’s edge and cross the river on ancient, hand-pulled rope ferries from The Saracen’s Head or 15th-century Ye Olde Ferrie Inne. Pleasure boats with commentary re-create the Picturesque Wye Tour, although summer 2012 visitors found the river unseasonably mud-colored from the torrential rains!

Siân Ellis

In Monmouth (see British Heritage, November 2012), the River Monnow flows below the iconic medieval gatehouse to swell the Wye on its way to quiet villages where you’ll find some good country pubs and The Crown at Whitebrook, a Michelin-starred restaurant with rooms.

It is hard to imagine now, but the Wye once clamored with industry hereabouts: Brockweir, on the cusp of the tidal river, was a major boat-building community, where ships came to unload their cargoes onto broad, flat-bottomed trows for onward journeys. At Red-brook, a center for copper and tinplate industries, the river ran red with iron ore; at Whitebrook, the waters churned white from washing rags for paper mills.

And so to Tintern Abbey, founded beside the river in 1131. The ruins that inspired Wordsworth and Turner are still an A-list attraction, supported by pubs, antiques and craft shops curling along the water’s edge. If this is the Wye’s grand romantic flourish, then its creamy swirl beneath Norman Chepstow Castle is its bold farewell. There, with inexorable purpose, this favorite river escapes without a backward glance into the Severn Estuary and the open sea.

Comments