Rising out of the rubble of World War II ashes, modern Coventry is indeed “The City of the Phoenix.” Coventry’s most famous heroine, though, remains Lady Godiva—personified by the affable Pru Porretta, opposite.

At the beginning of this new millennium, Coventry began to unearth its very first cathedral; the 11th-century remains of the only cathedral in England to be destroyed by Henry VIII.

Outside the new Priory Visitor Centre, which displays artifacts left from the ancient cathedral, is a very modern interpretation of the cathedral form. Among a quadrant of lime trees, planted along the outline of the original cloisters, recordings of local people’s reminiscences whisper to those sitting below.

The Cloister Gardens are typical of the regeneration that is a continual feature of Coventry’s 1,000-year history; even the coat of arms features a phoenix. This Midlands city has a fascinating story to tell and not just from oral history in the trees. Only an hour by train from London, a compact area encompasses remarkably three cathedrals, a real medieval jewel and excellent museums. And from Saxon Coventry onward, visitors can follow the story of the people’s celebrated heroine—Lady Godiva.

Read more

The legend of Lady Godiva, dating back to the 11th century, tells of her riding naked through the streets to protest a tax issued by her husband, Earl Leofric of Mercia. In fact, Leofric and Godiva were a far more substantial part of Coventry’s history, establishing the church that became the cathedral and many others. This attracted pilgrims and trade, laying the foundations of the city. After Leofric’s death in 1057, unusually, Godiva continued as a benefactor. In fact, The Doomsday Book recorded Godiva as the only female landowner in Britain.

Her ride was first chronicled 100 years after Godiva’s death. Her “nakedness” probably meant without her jewels or veil—being paraded as a commoner. Of course, that wouldn’t make her such an enduring icon, used by the city many times over the centuries to boost morale and the city’s fortunes. Next to the Cloister Gardens lies the most modern reference to Lady Godiva; she is the central star in a Hollywood-style tribute pavement. Centuries earlier, in 1667, the city tried for the first time to benefit from the Godiva story. The first of many Godiva processions with a young girl (or in early years, a young boy) riding on horseback through the town took place along with assorted floats.

Walking from the Priory Centre down the medieval cobbled streets, visitors reach the procession’s traditional starting point—St. Mary’s Guildhall on Bayley Lane—a beautiful example of medieval craftsmanship inside and out. Outside, folks can arrange to meet someone who knows exactly what it’s like to be part of the Godiva procession.

“My mother thought I’d make a lovely Lady Godiva. I said I would not, riding alone on a horse for three hours,” says Pru Porretta, “but you know when your mother goes on and on, so I just made the phone call.” Porretta’s phone call back in 1982, when she was just 19, led to a series of public interviews and selection as that year’s Lady Godiva. Almost 30 years later, Porretta is not only still the city’s Lady Godiva, but a well-known tourist guide and authority on the city’s history. She has a particular passion for Godiva’s life story. “This ‘chocolate-box’ Godiva is really unfair to the real woman, mother and grandmother…a fascinating and true story,” she says. Porretta was recently awarded the MBE for services to tourism, and her tours are highly recommended. Just look out for a tall woman in a full-length Saxon gown with a smile for everyone.

Inside the Guildhall, both the grandeur of the great hall and the more intimate rooms display a range of detailed craftsmanship; from the huge stained glass window to another Godiva image, this time carved in alabaster. Many rooms feature intricate oak panelling, and the grand 15th-century tapestry still hangs in the same place for which it was designed 500 years ago. To really appreciate the building, Godiva’s, the restaurant in the vaulted undercroft, is a great place for lunch or afternoon tea.

St. Mary’s Guildhall is as remarkable for the fact that it exists as for its fine carvings. The 14th-century building miraculously escaped untouched on Coventry’s infamous night of devastation during World War II, despite being yards away from St. Michael’s Cathedral, which was not so lucky.

To really appreciate Coventry’s wartime experience, visit the Herbert Museum, just 200 yards down Bayley Lane. Its modern lofty entrance, reminiscent of a cathedral itself, leads to a number of galleries, but the “peace and reconciliation” gallery is the most moving.

Visitors start by listening to the voices of those people living in Coventry on the night of November 14, 1940. “As the raids usually finished, this one went on and on,” recounts the voice of Shelia Burn. “My mother said, ‘Oh my God—the whole city is ablaze.’”

The bombing of Coventry did go on and on. In just one night, more than 30,000 bombs killed 554 people, destroyed 111 factories and devastated St. Michael’s Cathedral. The gallery displays many poignant images, but the single firefighter standing in the wreckage of the cathedral, now with just the walls standing, is particularly affecting.

Read more

The gallery continues with Coventry’s reaction to that night after the war was over. It was one of the first cities to reach out to others—becoming twinned with Stalingrad and then Dresden, the first two of its now 26 twin towns. Coventry is now a world-renowned center for peace and reconciliation, supporting refugees and hosting international conferences.

The Herbert Museum has several other notable galleries, as well as a light and airy café and a new history center with resources for tracing local ancestors.

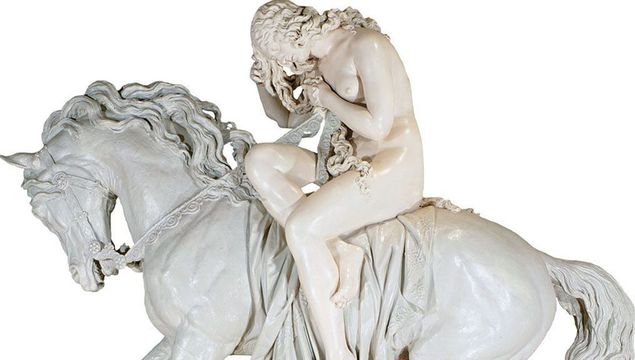

In the Godiva Gallery, the legend is seen through popular images over the centuries. The story’s popularity soared in 1842 after Tennyson wrote his poem “Lady Godiva.” Following his descriptions of her “looking like a summer moon” with “rippled ringlets to her knee,” there was a wave of romantic 19th-century paintings. Also not to be missed are the flickering black-and-white Movietone images of nervous Godivas heading the city procession, from the 20s to the 50s, sitting on anything from a cart horse to a racehorse.

The Coventry gallery depicts Coventry’s important industries: from cloth to ribbon making and then clocks and watches. In the 20th century, Coventry became a bicycle, motorcycle and car city; manufacturing automobile marques such as Daimler, Jaguar and Triumph. (For fans of all things with wheels, a 10-minute walk will take you to the well-laid-out Coventry Transport Museum with a huge range of authentic vehicles.)

Opposite the museum stand Coventry’s two most famous symbols of resurrection—the walls and tower of the old St. Michael’s Cathedral and the new cathedral consecrated in 1962.

Inside the old cathedral, the structure’s shell forms a peaceful courtyard, popular with visitors from all over the world and still used for occasional church services. The famous “charred cross,” formed out of two beams from the wreckage, now features as part of the altar with the inscription “Father Forgive” on the wall behind. Medieval roof nails were also formed into crosses, displayed in the new cathedral and sent to world leaders as peace symbols.

The day after the bombing, Coventry declared that it would build a new cathedral. They also later stipulated that any new design should preserve the tower, spire and undercrofts of the old cathedral. In fact, with Sir Basil Spence’s chosen design, none of the old cathedral was removed to make way for its modernist neighbor.

As well as a huge porch linking old and new, the west side of the new cathedral features a stunning 70-foot-high glass screen etched with saints and angels. As well as hinting at the modern interior of the new cathedral, it offers beautiful reflections of the old one.

As with St. Mary’s Guildhall, this new 20th-century cathedral displays works of modern artists of its time. The tapestry hung behind the altar is the world’s largest and was designed by Graham Sutherland. The sculpture on the front of the cathedral, depicting St. Michael and the Devil, is by Jacob Epstein.

The short, yet detailed, film of the building of the new cathedral, shown in the treasury area, is worth taking time for—particularly for traditionalists seeking to understand the architect’s vision of this very contemporary space. In 2012, even the newest of English cathedrals will celebrate its Diamond Jubilee. Queen Elizabeth II is due to attend as she did for the cathedral’s consecration.

Returning to the railway station and passing the shopping area rebuilt after the war, visitors see another image of Lady Godiva. This time on a large stone plinth inscribed with Tennyson’s poem, a bronze statue on horseback looks down on the passers-by, maybe wondering exactly where her story and the city will go next.

Comments