Like many of the tiny cove beaches along the Penwith coast, the fine sands and azure waters of the beach at Porthcurno give a Mediterranean flavor to southern Cornwall.Jim Hargan

Cornwall’s Penwith Peninsula has what may be the finest coast in all of Britain: nearly 40 miles of continuous, unbroken sea cliffs, with fine sand beaches washed into narrow cuts, and water the deep turquoise of the Bahamas.

The wide views from the flat, grassy clifftops reveal a landscape twisting like a fractal curve, little harbors sliced into big ones, small headlands jutting even farther out from larger ones. The cliffs change every few hundred yards, varying with the underlying rock, carved by the sea into precipitous drops and odd shapes, their colors ranging from grays to reds to deep purples and near-blacks.

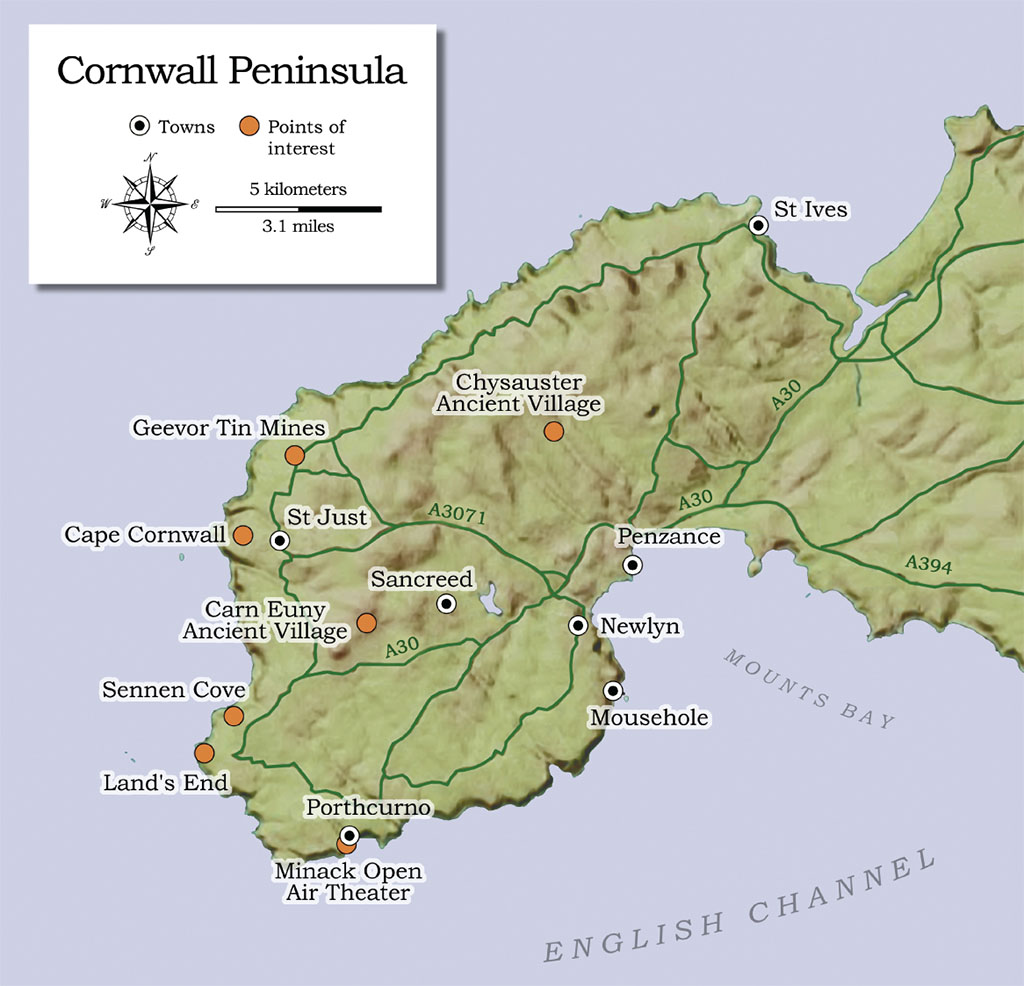

Penwith sits at the far end of England, 300 miles southwest of London, a cliff-ringed rectangular table attached to the tip of Cornwall. It’s a plateau formed from a huge mass of granite that squeezed like hot toothpaste into the surrounding sedimentary rocks—the same geology as its distant neighbor Dartmoor. At its center you’ll see rough, boggy moors that formed on the infertile, impervious granites; sheep graze the rolling terrain, and there is an occasional hillock to give a view. The moorlands end where the granite gives way to the native rocks, locally known as killas, once level but now tilted, crushed and burnt. Here you find farmland of the traditional English kind, with small fields surrounded by stone walls and hedges. Local folk live in farmsteads dispersed throughout the killas lands, ringing the central moors with a few villages scattered widely around its edges.

Penwith’s most stunning cliff scenery comes together at Cape Cornwall. Once thought to be the most southwesterly point in England, here the granites meet the killas at the cliffs themselves. The scenery is extraordinary, even for Penwith. A mound of a headland, gray and grassy, looms above an oval cove lined with rust-red cliffs (that’s the killas). Fishermen pull their small boats up to a simple quay at the base of the cove—no more than a ramp, really. A whitewashed stone farmhouse and a row of stone cottages sit at the foot of the headland, protected from the seas by strong stone walls. On the north side of the headland is a stone ruin with an old stone cross, which some claim is a 4th-century oratory, and others say is an abandoned farm building. At the top of the headland is a striking brick chimney, part of a tin mine that closed in the 1870s. The views from it are magnificent.

That chimney marks more than good views. It marks the southern end of nearly five miles of cliff-top chimneys, engine housings, mine shafts, even entire factory foundations, all abandoned, all ruinous—the relics of the last era of Cornwall’s famous tin mining. Here, where the granite met and melted the killas, is where tin formed, precipitating out of magmatic gases and fluids that rose in veins along the near-vertical bedding planes between layers of killas.

These veins can extend a half-mile deep, and run between the killas beds for miles as thin horizontal lines. Until very recently they represented enormous wealth and were the backbone of Penwith’s economy.

While today’s Penwith might seem indeed to be the end of England, it wasn’t always a remote corner; if you were a Phoenician or Roman trader, it would have been the first place in Britain that you saw on your way to pick up a load of tin ingots. Southwest England’s tin trade dated back at least to 1750 BC, when a ship carrying tin ingots sank in a river leading from the Dartmoor tin areas. The trade continued without break through the Celtic Iron Age, and may have inspired the Roman conquest of Britain in AD 44. Nor did it slack off during the Dark Ages, or medieval times. All these eras can be explored in Penwith.

Dolmens (locally called quoits) remain from the earliest epoch—strange structures of great stones, capped by a giant flat rock, thought to have been the centers of burial chambers whose mounds have long since disappeared. The prehistoric Celtic village known as Carn Euny lays out a grouping of stone foundations that mark an Iron Age settlement, with a mysterious fogou (pronounced foogoo), a rock-lined underground passage, at its center. Was the fogou a place of worship? Or a “cold room” where they kept their produce fresh? Possibly both. In nearby Chysauster village you can see a larger example built during the Roman occupation, although, unlike Carn Euny, you cannot enter its fogou. The Dark Ages are represented by stone crosses and holy wells, such as the Celtic cross that still stands by the parish church in Sancreed.

From the time of the Phoenicians and the Romans, traders have landed at Cornwall for tin. The cliffside Crown Engine Houses at Botallack Mine, built in the mid-1800s, have been silent since the mine, extending two miles into the Atlantic, was finally abandoned in 1914. Jim Hargan

Tin mining occurred anywhere that granite broke into killas, from Penwith to Dartmoor. From the Stonehenge era to the 18th century it was all done basically the same way: placer mining, along streams where the ore had been eroded from lodes and washed downhill. Steam engines brought in a radical change. Just as three millennia of exploitation had exhausted the placer deposits, miners discovered that they had the means to follow the near-vertical lodes downward and keep them pumped out, no matter how fast the water flowed into the tunnels. Penwith tin miners followed the lodes far under the water table, then miles out to sea. Giant tin mines lined the coast between Cape Cornwall and Pendeen Watch, their vast works spewing sulfurous, arsenic-laden fumes into the air, their tailings covering huge areas. Today, they are all abandoned; not a single tin mine survives anywhere in the United Kingdom.

The five-mile coastal walk through this area, a favorite with day trekkers, is one of the great experiences of Britain. The wild cliffs are brilliantly offset by the heavy crust of abandoned industry. Hearty sea thrifts colonize the once barren ground, giving a gorgeous display of great pink mounds in May and June. The ruins themselves are fascinating and often beautiful, dating as they do from an era of hand-cast local brick put up by artisan masons. One of the most dramatic industrial sights in Britain can be seen a bit more than two miles north of Cape Cornwall. Here the early 19th-century engine houses of the Botallack Mine perch precariously halfway down high cliffs, like two birds of prey; they pumped water out of tunnels that extended two miles out under the ocean. A bit farther on is a car park among ruins and interpretive signs courtesy the National Trust.

GREGORY PROCH

A mile farther, the Levant Mine’s remains to include a fully restored steam engine, owned by the National Trust and regularly powered up by local enthusiasts; the site is remarkably evocative. The finest tin site, however, is another half-mile along: Penwith’s last and largest mine, Geevor Tin Mine, now restored and an open-air museum. Closed only in 1990, its extensive above-ground facilities are preserved exactly as they were on its last shift—including chalk graffiti on the walls, some of it vulgar, much of it surprisingly poignant. Open and fully equipped are buildings such as the miners’ locker room, the hoist and equipment room, and the large ore processing plant, with its period equipment turned on during the tour. There’s a fine new museum on site that tells the complete story. Right now, the climax of the visit is a trip down an 18th-century tunnel that follows a surface load, giving an idea of the hard life of a miner. Within a few years, Geevor hopes to open one of the great 20th-century shafts as well, for a long elevator ride down to a tour of modern-era tunnels.

What happened to the mines? Starting in the 1950s, a consortium of British and Malaysian mine owners known as the International Tin Council had controlled world tin prices by buying up surpluses, even as nonmembers continued to open mines in other countries. In October 1985 the council ran out of money, and the world price of tin collapsed overnight. Geevor’s owners were one of the last to give up. The last miners were turned out in 1990, but not until May 1991 did its owners shut off the giant pumps that ran day and night, lifting a million gallons of water a day out of the tunnels. Penwith’s last tin mine was dead.

Jim Hargan

Without tin, the Penwith economy runs off its beaches. And what beaches! Golden sand, light and fluffy, runs down to a gently sloping shelf, framed by tall cliffs of twisted rock. On a sunny summer’s day the water is simply spectacular, the color of sapphire and crystalline in its clarity. And, unlike most British beaches, its waters are warm, as this is where the Gulf Stream washes up. Do you sun yourself lazily on the beach? Or trek along the grassy cliff tops? Why not do both? Some beaches exist only at low tide, and must be reached with a stiff hike and a steep climb down—the scenery enjoyed by the chorus of maidens in The Pirates of Penzance, as they sing “Climbing Over Rocky Mountains”.

Of course, the British love a good beach, so that Penwith’s—pretty much the best in the nation—can get crowded on a bank holiday. Remote parking lots are opened and then filled, while a steady stream of walkers avoid the parking problem by hiking in along the cliffs. Frankly, Penwith’s best beaches deserve the attention they get. Just south of Cape Cornwall, Sennen Cove forms a sand crescent 1.3 miles long, famed for its surfing, with a pretty (if touristy) village at its southern end. The good news: there’s plenty of parking. The bad news: the parking is at the top of the cliff, 260 feet above sea level and a good quarter-mile from the village.

From tiny harbors in pretty fishing villages such as Mousehole, both pleasure and commercial craft ply the warm waters surrounding the Penwith peninsula. Among the seafood prizes, a local favorite is Newlyn crab. Jim Hargan

While there

Sancreed is 2.5 miles west of Newlyn via the A30 and a signposted lane. Carn Euny (www.english-heritage.org.uk), another mile farther, is always open and free. Chysauster is 3 miles north of Penzance via the B3311 and a side lane (watch for brown signs); it’s open daily in season from 10 a.m., and charges £3 per person. One of the most accessible dolmens, Lanyon Quoit (www.nationaltrust.org.uk), sits beside a moor lane that runs between Penzance and Penwith’s northern coast, between Madron and Trevowhan.

The Levant Mine and Beam Engine (National Trust) is open and steaming every Friday all year from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., and on other days as well during the season; admission is £5.80, and includes an underground tour.

Geevor Tin Mine (www.geevor.com) is open daily during the season, and every day except Saturday during the winter, from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.; admission is £8.50, including the underground tour. Its café is said to serve the best pasties in Cornwall.

Porthcurno Telegraph Museum (www.porthcurno.org.uk) is open daily during the season, with restricted openings off-season; admission is £5.50. The Minack Theatre

(www.minack.com) has performances every weekday from mid-May to mid-September; when no performance is scheduled, it is open to sightseers for £3.50.

The St. Ives Park and Ride is at St. Erths Station, 4 miles to the south, and runs once or twice an hour between 6 a.m. and 10 p.m.; at £4 per adult return, it’s cheaper than the cliff-top parking lot. This local chugger spends 14 minutes following the coast into the center of town, a scenic and convenient location hard by the quay. Consult Britain’s National Rail Web site for schedules (www.nationalrail.co.uk).

Lands End (www.landsend-landmark.co.uk) charges £4 to park, plus a separate admission for each of its attractions; a combined ticket costs £10.95 for an adult and £6.95 for a child.

Jim Hargan

Porthcurno, three miles south, is even more scenic, and the hike in is easier (although the parking is worse). Here you find a classic cove beach washed up in a 300-yard gap between towering cliffs. A walk along the coast path to the clifftop gives wide views of the sparkling beach; from there you can see that there’s a second, hidden beach around the cliffs to the east, accessible only at low tide.

There’s more to Porthcurno than its beach. The first telegraph lines came ashore here, linking Britain with the Mediterranean countries, following the route of the early Phoenician and Roman tin traders. In the village, the Porthcurno Telegraph Museum inhabits the former international cable hub that formed here—underground, to protect it from attack. Exhibits include the early telegraph equipment, the way submarine cable operated and the people who created and ran the system. Above Porthcurno, perched beneath a clifftop, is the eccentric and wonderful Minack Theatre, an amphitheater carved into the cliff sides, itself spectacular and with spectacular views. Major companies from Britain and the United States perform all summer long on a stage backed by one of the most glorious views in Cornwall.

Despite its undeniable touristy flavor, Land’s End is a must-see for visitors to the Cornish southwest. Next stop, Canada. Jim Hargan

Penwith, like the rest of Cornwall, has always been dependent upon its harbors. With almost 40 miles of cliff, however, building a quay turned out to be a tricky matter of finding a slot that offered both protection from the weather and a place to put a road. If successful, fishermen and boat owners would crowd about, placing cottages in terraces that rise above the quay. In this way Mousehole (pronounces maow - zul) came about, one of the most picturesque fishing villages in Cornwall, with a stone quay dating from medieval times.

Three miles to its north, Newlyn anchors the southern edge of the cliff line. Unlike tourist-dependent Mousehole, Newlyn retains its working-class edginess, with a large commercial fishing fleet; its High Street, coarser than the tourist villages, fronts its large and handsome harbor. At the far northern edge of the cliff line, 39 miles by cliff-top walking but only 10 miles by car, sits the crowded, bustling and impossibly quaint town of St. Ives. It is jammed into a cliff-ringed area so constricted that driving is extremely difficult and parking strictly for locals with permits. Nevertheless, tourists crowd its streets, either walking down from large cliff-top parking lots or taking the railroad park-and-ride right to the town’s lovely old quay.

Penwith’s most famous spot is Lands End. When good maps became available during the 18th century, this remote point stole the title of “most south-westerly” from nearby Cape Cornwall—and immediately became a national tourist attraction. Since the 1980s, two succeeding owners have tried to reclaim its former glory, with some success. It’s pleasant, clean and airy, which exhibits both entertaining and educational. The entrance is by a parking fee no higher than that of the nearby beaches. This lets you walk all around, visiting the shops, cafes, a pub, and local crafters. Best yet, you can enjoy its fine cliffs, with a spectacular display of off-shore rock formations—the glory of Penwith.

* Originally published in July 2016.

Comments